Whitlam dismissal secrets unearthed from the archives of the Canadian governor-general

October 29, 2025

This newly uncovered material, exclusively published by Crikey, is the first indication from Sir John Kerr himself that Queen Elizabeth II approved of the position he had taken during his dismissal of Gough Whitlam.

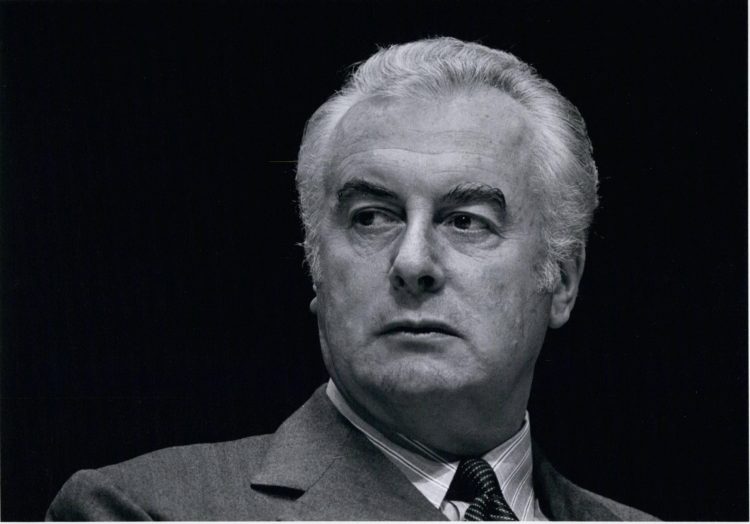

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the dismissal of Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam by governor-general Sir John Kerr, new details about Queen Elizabeth II’s view of Kerr’s action have been found in the archives of former Canadian governor-general Jules Léger.

Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam Government followed four weeks in which the coalition of opposition parties had blocked the government’s supply bills in the Senate, demanding Whitlam call an election before they would vote on them. Whitlam held a clear majority in, and the confidence of, the House of Representatives, and was in the process of calling a half-Senate election when Kerr dismissed him and his entire government without warning. In Whitlam’s place, Kerr appointed the leader of the opposition Liberal Party, Malcolm Fraser, as prime minister, without the confidence of the House of Representatives.

It is hardly surprising that this unprecedented vice-regal dismissal sparked intense debate and drove an equally contested history reverberating throughout the Commonwealth. Many key details about the dismissal remained hidden for decades, locked in the Australian archives and denied by the key protagonists, creating a distorted and incomplete history of that tumultuous episode.

It took nearly 40 years, for example, before the secret role of Sir Anthony Mason, then a High Court justice, was revealed as Kerr’s long-standing adviser and guide throughout 1975, who even drafted a letter of dismissal for Kerr. And it took 45 years and a High Court legal action — proceedings I initiated in the Federal Court in 2016 — to secure the release of the secret Palace letters between Kerr and the Queen. After years of denial, the letters finally revealed the role of the Queen, her private secretary Sir Martin Charteris, and Prince Charles, now King Charles III, in Kerr’s decision to dismiss the Whitlam government.

New Palace letters between Canadian governor-general Léger and the Queen uncovered in the Canadian Archives are a significant addition to our shared Commonwealth post-colonial history. In addition to Léger’s correspondence with the Queen, his meticulous notes of his meetings with both Kerr and the Queen add a further dimension to the history of the dismissal. They are of particular interest here for the new light they shed on Kerr’s shifting perception of his own actions in dismissing Whitlam and, most importantly, for the Queen’s view of it.

The approval of Prince Charles for what he described in a letter to Kerr soon after the dismissal as his “right and courageous” action, and the approval of royal eminence grise Lord Louis Mountbatten, are now well known. But Léger’s meticulous notes of his discussions with Kerr are the first indication from Kerr himself that the Queen herself also approved.

Léger met Kerr twice, once in London during the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 and then in Canada in 1979, 18 months after Kerr’s reluctant resignation as governor-general. Léger’s observations on the marked change in Kerr’s demeanour and confidence regarding his dismissal of Whitlam make interesting reading. In his letter to the Queen of 2 September 1977, Léger includes a five-page confidential note of an hour-long meeting with Kerr, accompanied as always by Lady Kerr, at Claridges Hotel in London.

Léger’s account highlights Kerr’s preoccupation with defending his position in dismissing Whitlam. Kerr’s conversation, Léger writes, was “mainly dominated by a defence of the position he had taken during the Australian constitutional crisis”, and his thoughts were directed “almost exclusively to that”. Léger describes Kerr’s remarks as “a plea pro domo sua” — a plea in his own defence — reflecting the obsession with justifying his position that had overtaken Kerr’s post-dismissal fall from grace.

Léger likens democracy to a clock that restarts with every election and “a governor-general who intervenes in the democratic process of his country”, as giving a tap to the “democratic clock”. He would leave it to the experts, Léger added, to argue over whether this “tap” by Kerr was democratic or not.

Most powerful is Léger’s metaphoric imagery of the governor-general as “like a bee” that can sting only once: “A governor-general can intervene just once to influence the democratic game, after which he must leave. He is like the bee that can sting only once and then dies… That is the case for Sir John Kerr.”

Charteris replied: “The Queen was … very interested to read your note on Sir John Kerr and in particular your reflection that a governor-general can only give one tap to the democratic clock!”

In a subsequent note, Léger details his meeting with the Queen in London at that time, during which they also discussed “the case of Sir John Kerr” and the Palace’s obvious desire that Kerr resign. Léger reveals the Palace’s intervention with Kerr to end his tenure as governor-general in this exchange.

In the aftermath of his dismissal of Whitlam, both the Queen, through Charteris, and Prince Charles had pleaded with Kerr not to resign, since, as Charteris wrote, “to do so could only be interpreted as a belief on your part that you had acted incorrectly”. Eighteen months later, however, Kerr’s bibulous excesses — which had led to him falling face-down in the mud at the Tamworth Show while putting the gold medal around the prize bull, and his attempt, swaying perilously, to hand the Melbourne Cup to the winning jockey — had led to immense pressure on Kerr to resign, and he would not go. The Queen, Léger recounts, told him “that the Palace had intervened” to convince Kerr to resign as governor-general. Kerr’s resignation was announced on 14 July 1977 soon after he met the Queen in London.

In 1979, Kerr and Léger met again, at Rideau Hall, the Canadian governor-general’s residence in Ottawa. The dismissal was once again Kerr’s major preoccupation. This time, however, as Léger recounts in his note of their meeting, Kerr appeared less certain and “rather defensive” about the position he had taken. Léger notes the change as Kerr appeared then to doubt and even to question his action in dismissing Whitlam: “Sir John is now rather defensive when he talks about the action he took, whereas when I met him in London, he was sure of himself. He is now less sure and is asking himself questions."

The most dramatic revelation by Léger, however, is that Kerr told him during this discussion about “the position he had taken” that “the Queen approved of his position, as did Lord Charteris. He adds that he is convinced that he served the monarchy well in Australia”, Léger notes. Asked by Léger whether “the monarchy in Australia had suffered as a result of the position that he had taken”, Kerr insisted to the contrary that “he had served the monarchy well in Australia”. The republican wave “stirred up by the crisis his action caused has since completely disappeared”, Léger noted.

Secrecy, collusion and intrigue

These unfolding revelations have transformed the dismissal history; what was once seen as the solo action of an isolated governor-general, we now recognise as a carefully planned vice-regal intervention steeped in secrecy, collusion and intrigue. The critical factor in this dynamic process of historical reassessment is that archives make history. Archives are the bedrock, the empirical base, on which we craft a documented story of the past, and when our access to archives changes, the history changes with it.

This direct correlation between archives and history is why the history of the dismissal continues to evolve, with a new iteration as significant archives are released. Kerr’s unpublished manuscript, Triumph of the Constitution, in the National Archives of Australia is a case in point. Kerr labours again, and again, over the events of 1975 in a vast validation of his controversial use of the reserve powers of the Crown to dismiss the elected government. Reading the draft, it is entirely understandable that this apologia remained unpublished at the time of Kerr’s death. Nevertheless, these unpublished ruminations give an important insight into his thinking and shifting political alignment, laying bare his support for the Liberal Party and denigration of Whitlam’s ascent in the Labor Party:

As the years passed I became more conservative and, although not joining the Liberal Party, I supported that party and not the Labor Party within which Whitlam was growing in power and position. I thought he was too much of a political smart alec.

At this point, Kerr’s in-house editor has written in the margin, “I’d definitely cut this. It could be used against Sir John” (italics in original), thereby continuing the myth, should the manuscript ever be published, that Kerr was “a Labor man”.

Despite the National Archives’ episodic release of files from Kerr’s papers, requests to access numerous files relating to the dismissal have met with a series of obstacles: unconscionable delays of months and even years beyond the legislatively required 90-day response time – the longest I’ve waited for a response is 13 years. Even when archives are eventually released, extensive redactions can leave them incomprehensible and of limited utility.

Compounding these obstructive delays has been the unexplained disappearance of vice-regal documents such as the Government House visitor books for 1975, the destruction of files including Gough Whitlam’s ASIO file and the accidental burning of an entire box of Kerr’s letters from significant royal and other supporters in the Yarralumla incinerator while in the care of the governor-general’s official secretary, David Smith.

And let’s not forget that public access to Kerr’s correspondence with the Queen relating to the dismissal, the “Palace letters”, which is an absolute trove of historically significant royal correspondence, required years of legal action and a High Court order against the archives to secure.

It was a tale of two archives, therefore, when I approached the Canadian Archives for access to the Canadian “Palace letters” – correspondence between the Queen and the Canadian governor-general at the time of the dismissal, Jules Léger. The contrast between our National Archives and their facilitation of public access could not have been starker.

Within days of my request, the Canadian Archives had sought access on my behalf from the Léger family, granted it with no conditions attached, and a digitisation request was submitted. Five weeks later, the entire Canadian Palace letters between governor-general Léger and the Queen from 1974 to 1978 had been opened, digitised and were now sitting on my desktop – no redactions, no delays and no years of legal action.

Léger, who was himself a most interesting governor-general — that’s another story — writes to the Queen in French despite clearly being bilingual, and addresses her simply as “Madame”, a marked contrast to our deferential governor-general Kerr’s royal “sycophantic grovelling”, as Malcolm Turnbull termed it.

An end to obstruction

While the approval of Charteris, Prince Charles, and Mountbatten has been previously revealed, this newly released Canadian material is the first time the Queen’s own approval has been directly canvassed by Kerr. It is a powerful reminder of the importance of archives to history.

Fifty years after the dismissal of Whitlam, it is a national disgrace that the full story is still yet to be told, as more than a thousand files relating to the dismissal remain closed by the National Archives of Australia. This is intolerable for our preeminent collecting institution whose core functions include “to make public” Australia’s historical records.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Arts Minister Tony Burke must act now to end this obstruction and call on the archives to open all of its files on the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in the interests of our history. After 50 years, it’s time.

Republished from Crikey, 27 October 2025

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.