World water in crisis

October 7, 2025

Almost two-thirds of the world’s rivers are in a dire condition, either drying up or supercharged with floodwaters, according to the latest report on the emerging global water crisis by the World Meteorological Organisation.

The WMO is the body that sounded the first official warning about climate change, back in 1979. Now it is the latest voice heralding a looming catastrophe in the world’s freshwater supply.

Half the world’s people are already experiencing water scarcity at least one month of the year, according to UN Water. By 2050, three quarters of humanity will face drought and water supply shortfalls.

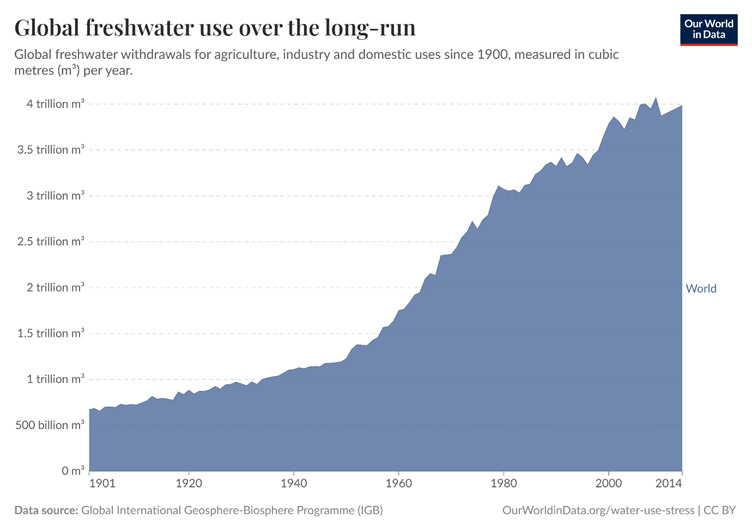

On our planet, only 2.5% of all water is fresh. Of that, 2% is in the form of ice or snow and only 0.5% is liquid, available for use. Humans use about 4 trillion tonnes of water every year – a prodigal rate of consumption, mismanagement and waste that has grown fourfold since mid-21st century. Food production accounts for 72% of that water.

Clashing demands from megacities, mining, farming, manufacturing and the energy sector is combining with climate disruption to spark major water shortages across the world’s semi-arid and arid regions – while floods are exploding in the tropic and temperate regions. While the global population is projected to rise 21% from the present 8 billion to 9.7 billion in 2050, global water demand could rise by 20%-30% over the same period.

“Across the water cycle, extremes were evident,” the WMO says. “Rivers, reservoirs, lakes, groundwater, and glaciers all showed significant departures from normal. While parts of Africa, Europe, and Asia were inundated by flooding, South America and southern Africa endured severe drought. Glaciers continued record ice loss, adding to sea level rise. These events brought widespread human and economic costs.”

The climate crisis will continue to build for decades to come – but the water crisis is here now and has been building since the early 1980s. Overdemand for water and man-made climate disruption are twin evils now combining with fatal consequences for humanity. While the global population is projected to rise 21% from the present 8 billion to 9.7 billion in 2050,5 global water demand could rise by 20%-30% over the same period.

River ruin

Barely a third of the world’s rivers are still functioning normally, the WMO says. In 2024, 60% of river catchments worldwide displayed abnormal behaviour when compared with the previous three decades, 1991-2020.

Many of the world’s most famous rivers have run dry at times in recent years, the Rhine, Danube, Loire, Yangtse and Colorado being examples.

At the other extreme, flooding in 2024 hit Central and Northern Europe and parts of Asia, including the Danube, Ganges, Godavari and Indus basins. In many cases, floods are made worse by excessive land clearing and poorly designed works in the catchment.

Drought affected much of South America, notably the Amazon, São Francisco, Paraná and Orinoco basins. In West Africa, extensive floods hit the Senegal, Niger, Lake Chad and Volta, basins while in southern Africa the Zambezi, Limpopo, Okavango and Orange suffered far-below-normal conditions. North American rivers (Mackenzie, Fraser, Nelson, Churchill) experienced below-normal to much-below-normal discharge, while the Mississippi returned to normal after drought in 2023.

The world’s main rivers are also foul with a cargo of silt (eroded soil), industrial and mining discharges, mercury, N and P fertilisers, drugs, toxic algae, human waste and urban runoff. The State of the World’s Rivers provides an up-to-date report on this defilement. It lists the Hai Ho, Wisla, Dneiper, Tigris-Euphrates, Yellow, Danube and Mississippi as the seven filthiest rivers on Earth – but many others are not far behind.

Riverflow worldwide is disrupted by over 50,000 dams, many of them now silting up from their ruined catchments. Riverlife — fish, birds and amphibia — is the most endangered class of the Earth’s biota.

Vanishing groundwater

Groundwater is running out in practically every country in the world where it is used to grow food. This poses a direct threat to both food and water security and human health in northern India, northern China, Central Asia, the central and western US, the Middle East, North Africa and Central America.

Subsurface water makes up 99% of all freshwater on the planet – and after use, takes thousands of years to replenish. For example, scientists estimate it may take around 6000 years to refill US’s Midwestern Ogalala Aquifer with the water extracted in the past 150 years.

Groundwater is the most heavily extracted raw material on Earth, with consumption now estimated to exceed 1000 cubic kilometres a year. Advances in pumping and energy led to massive increases in extraction, almost always at rates far higher than it naturally recharges.

Groundwater supplies more than 40% of the world’s food, notably in regions such as the North China Plain, Northern India and Pakistan, North Africa, the Middle East and Midwest America. Now it is being asked to meet the raging thirst of the megacities, posing a direct threat to their food supplies.

Groundwater is also vital for the environment, supplying most of the water we can see in rivers, lakes and wetlands. Its loss can cause entire landscapes to dry out and die. It is now adding to sea level rise.

Spreading deserts

Described as “the greatest environmental challenge of our time” by the UN, desertification is ripping the heart out of green landscapes globally.

Driven mainly by land clearing, human mismanagement and climate change, it:

· Spreads by around 100 million hectares a year, equal to losing 4 football fields a second.

· Affects over 40% of the Earth’s land area, and 3 billion people.

· Combined with land degradation and drought, costs the global economy more than $1 billion a year.

· Can be reversed by rewilding and reduced use of land – but isn’t.

Shrinking glaciers

The icepack on high mountains worldwide is diminishing, emptying the rivers it once fed in every inhabited continent and confronting countries like India, Pakistan, Chile and China with a permanent state of drought and water scarcity in key food-growing regions. Continents such as Europe could become ice-free.

The loss of land ice is speeding up, scientists warn. Glaciers shed 231 billion tonnes of ice a year from 2000 to 2011, but that rose to 314 billion tonnes in the next decade, and then set a record mass loss of 548 billion tonnes in 2023, according to a study in the journal Nature.

In total, the world’s glaciers are smaller by seven trillion tonnes of ice since the year 2000, and have added about 18mm to sea level rise.

Disappearing lakes

The Earth’s 100 million lakes make up 90% of its surface freshwater. They are in the same plight as its rivers – either drying up, silted, or else flooded and badly polluted. Led by the Aral Sea — once the world’s 4th largest lake — major lakes are vanishing in Central Asia, China, sub-Saharan Africa and South America.

The primary causes of lake loss are over-extraction of water, as in the case of the Aral and Caspian Seas, combined with climate change, as in the case of the great lakes of the Andes and Africa, and reclamation of land for urban development or farming. Toxic inflows of urban sewage, runoff, pesticides and industrial waste are turning the waters of even well-filled lakes foul and green.

“Today, some of the world’s best-known and most important lakes are a shadow of what they were just a few decades ago,” says Dianna Kopansky of the United Nations Environment Programme. “We need to reverse this decline. If we don’t, it could be calamitous for the hundreds of millions of people who rely on lakes for their survival.”

Thirsty cities

Around the planet, some of the world’s most prominent cities are already outrunning their water supplies. Notable among these are Sao Paulo (23 million), Bangalore (14m), Beijing (23m), Cairo (23m), Jakarta (12m), Moscow (13m), Istanbul (16m), Mexico City (22m), London (10m), Tokyo (37m), Miami (7m), Cape Town (5m), New Delhi (35m), San Diego (1.3m) and Las Vegas (670k).

By 2050, water scientists estimate, around 240 cities worldwide will be short of water, including at least 10-20 megacities (with populations over 10m).

Illustrating the trend, the Indian capital New Delhi faces a severe water crisis, with a daily demand of approximately 1290 million gallons per day, while the Delhi Jal Board currently produces only 1000 MGD. The deficit is imported from nearby states. Groundwater supply has dwindled causing shortages and poor water quality. The situation is made worse by climate change, erratic rainfall, pollution and a population that will grow to 39m by 2030 .

Water wars

Humans have fought over water resources throughout history, but the risks are increasing today. A UNU analysis (2023) found more than half the world’s population now lives in water-insecure countries.

The late Pope Francis warned that humanity could be facing water wars. Each of the last four UN secretaries-general — Antonio Guterres, Ban Ki-Moon, Kofi Annan and Boutros Boutros-Ghali — has warned of the dangers of world water scarcity and of resulting conflict.

In one of the most ominous developments, financial speculators have begun to view scarce water as another “cryptocurrency” which they can gamble with for profit. The likely result will be to price it out of the mouths of citizens and fields of farmers – and one of humanity’s most basic rights will become just another roulette chip.

Many solutions to the world water crisis have been proposed, chiefly around greater efficiency in water use by cities, farmers and industry, reducing transfer losses, filtration, desalination and recycling. Thus far, however, the global outlook is continuing to deteriorate in line with population and demand growth, and global heating.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.