‘Mr Whitlam’s style’ – Part I

November 10, 2025

“I had no contemporary political heroes. I preferred Labor values to Liberal ones. I believed in a mixed economy. I disliked the people who’d got us into the Vietnam war. I was grateful to those who’d got us out. I admired Gough Whitlam, but not as much as he did.”

Senator John Button, As it happened.

The dismissal of Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam by Queen Elizabeth’s Vice-Regal representative, Sir John Kerr, in November 1975, was an extraordinary event. For almost 50 years a debate has raged about why the governor-general took the unprecedented action he did. This essay represents a further attempt to answer that question.

First and fundamentally, however, we should recognise the enormity of Kerr’s action. It was based on ”reserve powers” in the Westminster system that Australia’s senior law officers considered were obsolete. As proposed in a recent study by two Oxford University academics, Iain McLean and Scott Peterson, there was no relevant precedent, at least since the ratification of the Statute of Westminster, for the dismissal of a prime minister who enjoyed the confidence of the lower house in Parliament. In addition, the replacement of a prime minister before the end of their term by an Opposition leader who then went on to win the resulting election represents another unique outlier among democracies operating under the Westminster system.

Why then did the governor-general make the decision he did? Some attempts to explain the dismissal have focused on a search for a “smoking gun” in the context of a possible conspiracy. Did the governor-general collude with the Opposition to get rid of Kerr? Was the CIA involved in destabilising a democratically elected government in Australia as it was in Chile? If so, what role did the White House play? Or the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6)? Or the Palace? Was the Queen a player in all this? Or did Kerr load and fire the gun on his own initiative?

The unfortunate fact was that after three tumultuous years in office, Whitlam had made a large number of enemies, some of them very heavy hitters indeed. Kerr would have been well aware there were powerful people at home and abroad who would have liked nothing better than to see the back of the Australian prime minister. A good starting point for any investigation of Whitlam’s defenestration, therefore, is to consider the question of cui bono. Who would benefit from his dismissal?

Whitlam had a commanding presence, a towering intellect, was full of creative ideas, could rise to great oratorical heights and was in many ways an inspirational leader. Yet, arguably, despite the government’s immense achievements that changed the nation, on a balanced view he was not a great prime minister. He was certainly immodest, probably arrogant, with a brimming self-confidence that fed a conviction that he had nothing at all to be modest about. He was not a reliable strategist and often unwilling to compromise. His judgment was uncertain, particularly in regard to people. He was a loner and not a team player.

In some ways, Whitlam was his own worst enemy. This was reflected in his style. Whitlam could rarely resist the temptation of the clever quip or the wounding barb, however ill-judged, while routinely neglecting to consider the potential impact on his target. Although it might be tolerated in Australia’s more rumbunctious political arenas to call the Queensland premier a “Bible bashing bastard”, such invective was inappropriate overseas. In taking on the foreign affairs portfolio in addition to his own, the prime minister displayed an almost risible lack of self-awareness. Diplomacy was a very long way from being his strongest suit.

The Whitlam Government came to power with an extremely ambitious reform agenda, both in domestic and foreign policy. In implementing his program, it would face significant opposition from entrenched interests. Neither Whitlam nor any member of his Cabinet had previous ministerial experience, even at the most junior level. In order to implement his program, Whitlam needed an influence strategy to promote the legitimacy of his government and the mandate he had won. If he could negotiate some kind of accommodating modus operandi with his opponents, his prospects of success would be improved.

Progressive governments are generally at a disadvantage in Australia because of the difficulty of their winning a majority in the Senate. The Australian Constitution puts urban dwellers in the big cities of Sydney and Melbourne at a disadvantage because every state was allocated the same number of seats in the Senate. Thus, both Tasmania, with a population of 400,000 in 1974 and New South Wales with 4.5 million each had 10 seats in the Senate. Paul Keating later referred to the Senators who benefitted from this inequality, somewhat inelegantly, as “unrepresentative swill”. This system was designed to protect the interests of the smaller states, but it generally favoured the conservative side of politics. The Whitlam Government’s lack of control of the Senate, for all but one of its three years in office, ultimately proved fatal to its survival.

Anderson et al propose that “loser’s consent is critical for democratic systems to function”. This consent was clearly lacking on the part of the former government, now finding themselves on the Opposition benches in Parliament. After 23 years in power, the conservatives had developed a sense of entitlement. In the first Parliamentary sitting after the election, the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Reg Withers, known as the “Toecutter”, denied the legitimacy of the Whitlam Government and its extensive mandate for change. Reflecting an idiosyncratic view of democracy, in a speech on the first sitting day after the election, Senator Withers dismissed Labor’s victory as the result of “temporary electoral insanity” on the part of the Australian community. He was ominously prophetic of the cause of Whitlam’s ultimate downfall: “The Senate may well be called upon to protect the national interest by exercising its undoubted constitutional rights and powers." Withers was clearly unsympathetic to the concept of loser’s consent.

While Withers’s conduct was unacceptable, however, the new government team did little to build productive relationships with members of the Opposition that oil the wheels of parliamentary business to the benefit of both sides. Australia’s written constitution is based on Britain’s constitutional practices which are not codified in one document but are contained in laws and honoured in conventions that have developed over centuries. Of particular importance in Whitlam’s downfall was that the Opposition overturned sensible conventions that had developed since 1901 and had never been flouted before. In practical terms, for example, the idea, that any time it felt it could win an election an Opposition should be able drive a government to the polls by denying it the funds required to undertake its regular business, was absurd. This suggests there was an unusual level of antagonism to the Labor Government, a hostility that ministers should have tried harder to understand and defuse.

Whitlam was a great parliamentarian and often genuinely funny, but his wit could leave lasting scars. For instance, did he have to say, quick as a flash, “Comrade, I do remember” when an opposition MP concluded a speech with the words “I am, after all, a country member”? He was lucky his first governor-general, Sir Paul Hasluck, was of the forgiving kind because, when Hasluck was a minister, Whitlam had flung a glass of water at him in the House of Representatives.

He was not so fortunate with another former political adversary, Sir Garfield Barwick, now Chief Justice of the High Court, with whom he regularly had jousted in Parliament. Whenever possible, Barwick found against the Whitlam Government in his judgments. Just before the dismissal, Kerr, quite improperly, asked Barwick to provide an advisory opinion on the governor-general’s power to sack the prime minister. In a matter that was highly contestable, and which later might come before him for judgment in the High Court, Barwick’s letter in reply virtually proposed it was Kerr’s duty to do so.

Australia’s allies and partners overseas had generally grown used to working with friendly governments in Canberra that provided a productive and unchallenging relationship. They were in for something of a shock. Not only did Whitlam propose a major change to a foreign policy more independent of the US, but he also had an egalitarian notion that, within Australia’s overall alignment to the West, there should be equality in relations between countries. This implied, for example, that Australia’s relationship with Luxembourg should be placed on the same level of importance as that with our main ally, the US, and the colonial “mother country”, Great Britain.

In the case of the US, it took Whitlam no time at all to enrage both US President Richard Nixon and his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger with a letter criticising the bombing of North Vietnam at Christmas in 1972. While other nations’ leaders were equally critical, it was Whitlam’s style that aroused in the recipients a uniquely high level of fury. As Kissinger made clear, it was Whitlam’s air of moral superiority and placing the US “on the same level as our enemy” that caused the outrage. Kissinger reported that Nixon was also particularly exercised by “Australia treating the US on a par with other foreign countries”.

This led to the president putting Australia on his private ‘shit list’ of countries, second only to Sweden. He despatched a new ambassador to Australia with the terse instruction, “Marshall, I can’t stand that cunt”. Further icing on the cake came with the CIA advising its staff that its Australian partners might as well henceforth be regarded as “North Vietnamese collaborators”.

The Whitlam Government’s relationship with the US never recovered from this early imbroglio. Returning to the question of cui bono in November 1975, with Nixon having resigned by then over Watergate, of all the overseas heavy hitters keen to see the back of Whitlam, Kissinger would have been at the very top of the list.

While Whitlam’s egalitarian views on foreign policy might have some resonance in the dusty corridors of academe, in the case of the UK the prime minister surely could have pretended that some countries were more equal than others. The de jure head of state of both countries, after all, was embodied in Queen Elizabeth. Yet for the first time a Foreign Affairs officer, Tim McDonald, was appointed to the position of Official Secretary at Australia House. His main task was to organise the operations of the High Commission “to reflect Whitlam’s conviction that our relationship with the UK should be managed on a basis similar to other foreign countries”.

There was no reason why the relationship with the UK should not have been productive. There was no personal dynamic, however, between the two prime ministers, who rubbed each other up the wrong way. Ted Heath was a testy, humourless character, very different to Whitlam. His focus in foreign affairs was the European Community, rather than the US, and he had very little interest in the Commonwealth. Heath had contacted Whitlam early in the new government’s term seeking assistance with some matter of immigration. Whitlam had other fish to fry and gave a cursory response. As a result, the British High Commissioner in Australia, Sir Morrice James, briefed his government that the new Australian prime minister was “wayward, arbitrary and doctrinaire”. This, of course, was a confidential briefing. Characteristically, Whitlam made his view of Heath public. In a speech he subsequently delivered at Washington’s National Press Club, he declared the British prime minister to be “a thoroughly, consistently, forthrightly, negative man”.

The main item on Whitlam’s agenda on his visit to London in June 1973 was to eliminate the right of Australian states to appeal to the British Privy Council, which he regarded as a “colonial relic”. Heath took a relaxed view of the issue, wanting to ensure undefined British interests were given careful consideration. Nevertheless, according to Jenny Hocking, while not willing to put the Privy Council issue on a fast track, Heath did propose a quick resolution of the archaic system by which Australian state governors were instructed by the British Government. In the light of future events, it is a pity that Whitlam did not take that issue forward. It played a part in the 1975 supply crisis.

In early 1974, a Labour Government under Harold Wilson replaced Heath’s conservatives. With two traditionally fraternal parties in office, Australia’s relations with the UK should have improved. Yet, it is difficult to find a record of any major interaction between the two countries before November 1975. In early 1976, however, Heath attended a congratulatory luncheon in London for Kerr.

By the end of 1973, Whitlam’s escapades in foreign policy had come to the attention of Australians. On ABC TV, a popular song based on the antics of a gauche Australian at large in London was adapted to lampoon the adventures of the “wild colonial man” who had taken up residence in The Lodge.

In contrast to Whitlam’s testy relationship with Heath, however, his efforts to modernise the monarchy seemed to find favour with the Palace. Elizabeth appeared happy to formalise her role with the title of Queen of Australia and she provided no opposition to a new national anthem and honours system for Australia. No doubt she gritted her teeth while smiling through some of Whitlam’s speeches, that included witticisms at her and prince Philip’s expense, with the prime minister once making reference to the “Queen of Sheba”.

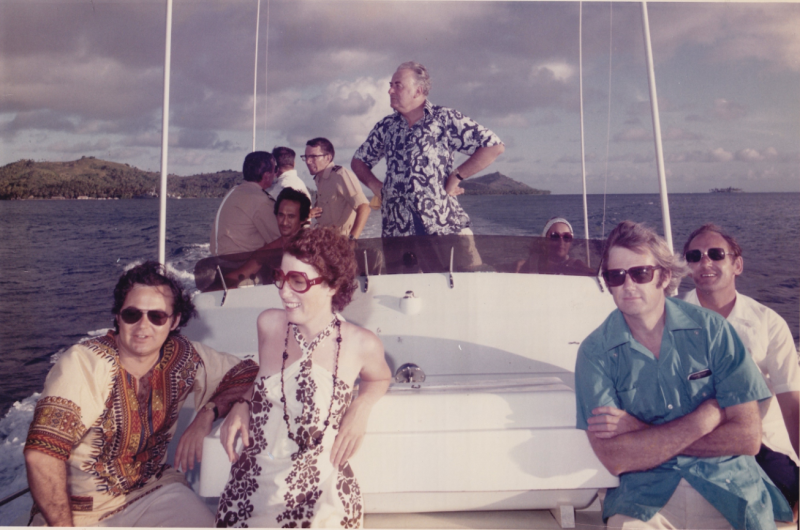

On another occasion, on the Royal Yacht, she told John Menadue, secretary of the prime minister’s department, that “Mr Whitlam has been rude about my family”. The prime minister had advised the Queen that while he was happy for Australia to fund visits by the royal principals, the nation’s generosity did not extend to others in the family, whom he may or may not have referred to as “minor royals”. This event, minor though it was, caused another unnecessary perturbation. It was poor judgment to raise such concerns, legitimate though they no doubt were, at the head of state level. Whitlam should simply have asked Menadue to refer the issue to the Australian High Commission in London, where McDonald’s tasks included liaison with the Palace.

Lèse-majesté, however, is not a crime in Australia or Britain and, over many years, the Queen’s commitment to the Commonwealth had enabled her to meet a wide variety of national leaders, far removed from the world of stuffy courtiers and pompous members of the British establishment. Hocking shows that a French-Canadian governor indulged his innate republican instincts by writing to the Queen in French and addressing her as “Madame”. Australia, particularly at that time, played a major role in the Commonwealth and Whitlam was an important leader within the group.

When we ask the question “cui bono”, it is difficult to see how in any respect the Queen would benefit from Whitlam’s dismissal. She would have understand all too well the risks to the Crown if her Vice-Regal representative should elect to dismiss a national government in a manner not seen under the Westminster system since 1783. Her main interest was in ensuring that the monarchy could demonstrate it had no involvement at all in what was clearly an issue that an independent Australian administration had to resolve. The Queen’s ability to deny any involvement in the affair needed to be not only plausible, but demonstrably true.

This conclusion, however, does not necessarily apply to the Palace more generally. While the Queen needed scrupulously to segregate her obligations to the Australian Crown from those of the British head of state, there could be problems if a courtier who owed his allegiance to the Queen of England sought to provide advice to the governor-general in Australia. McLean and Peterson identify the Queen’s principal private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, as one of a number of “irresponsible advisers” to successive monarchs whose willingness to provide unequivocal advice was matched only by their lack of any credentials in constitutional law. In response to the claims that Charteris’ letters to Kerr contain no smoking gun, McLean and Peterson write “we see at least a whiff of smoke”.

In the quest to identify the beneficiaries of Whitlam’s untimely demise, the intelligence agencies at home and abroad provide rich grounds for investigation. Whitlam was the first prime minister to discover Australia was a member of the Five Eyes, then known as the UKUSA agreement but, as the chief of MI6 discovered from the head of Australia’s Royal Commission into the intelligence services, he was preparing to become their greatest disruptor.

In relation to cui bono, while accepting that the security agencies are instruments of their respective governments, it was proposed later that both the CIA and MI6 would have been gratified by Whitlam’s dismissal. A different question relates to Australia’s domestic agencies and the extent to which their loyalties were divided between their allegiance to the Five Eyes and their own prime minister.

Again, Whitlam was his own worst enemy. Six weeks before his dismissal he dismissed Peter Barbour, the head of ASIO, who had been so demonstrably loyal to Whitlam that the CIA wanted to get rid of him. Barbour was dismissed for having an affair with a staff member, a misdemeanour which, if punished universally, would have decimated the senior ranks of the 1970s public service. Three weeks later, in a raging fury, Whitlam sacked Bill Robertson, the highly regarded head of ASIS, who had done nothing to deserve dismissal. To compound his bad judgment, Whitlam allowed Robertson to remain in his office for nearly three weeks, where he prepared a brief for Malcolm Fraser and enjoyed the benefit of a secure telephone connection to Bill Colby at the CIA and Maurice Oldfield at MI6.

On 11 November 1975, motivated by rather different sentiments to most in the throng in front of Parliament House, Robertson was able to indulge in some understandable Schadenfreude as he stood and listened to Whitlam’s angry valedictory.

Finally, we come to the governor-general. As Paul Kelly points out, Whitlam selected Kerr for the post without undertaking any due diligence. He failed to understand Kerr’s obsession with the reserve powers and, like an arsonist, his dream of exercising them. Whitlam’s jokes that it was a race to the Palace to see who could sack the other first, together with his constant belittling of the governor-general and arrogant assumption Kerr would do what he was told, were all fatal misjudgments.

Although governors-general were constrained to take advice only from their prime minister, we know Kerr consulted members of the establishment apart from High Court judges. The wider he spread his net, the more he would discover important people who would have been pleased to see the back of the prime minister. Kerr would have known that Fraser was supported overwhelmingly by the Australian establishment, including a former deputy director of ASIS deeply opposed to Whitlam. Another member, Australia’s elder statesman, Sir Robert Menzies, whose advice Kerr would have coveted above all others, wrote to him in support of exercising his powers. Although marked “Confidential”, the letter went straight into the bag to the Palace.

One of Whitlam’s many problems was an absence of influential support from Australia’s establishment. He had alienated too many important people. Ultimately, he faced the tragedy of Martin Niemöller: “there was nobody left to speak out for me”.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.