After 50 years, it’s time we called it a coup

November 13, 2025

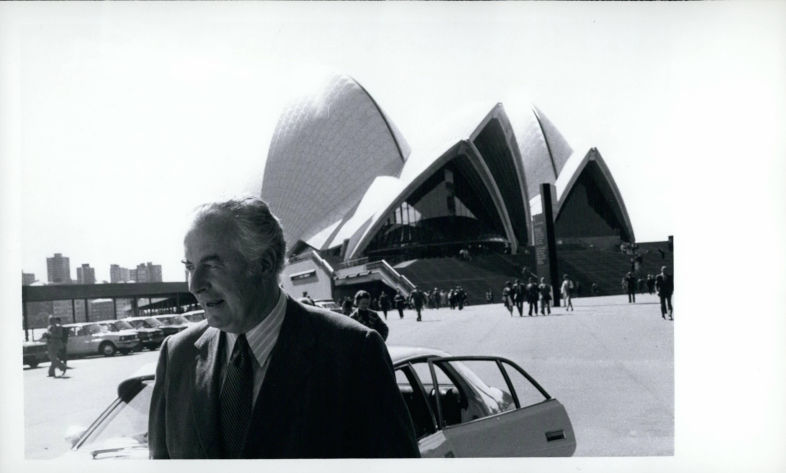

Fifty years ago today, an elected government was ousted by a representative of a hereditary monarchy. Broadly, Australian society has still not grappled with these events.

Australia experienced a conservative coup – and a majority of voters were at least indifferent. On this anniversary, I hope that a broader swarth of Australian society will confront that reality and re-examine the events.

We call 11 November 1975 “The Dismissal”. The name implies a one-off, singular, almost whimsical event. The reality is that the events of 1975 fit the definition of a coup. In academic literature, a coup is defined as “illegal and overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive”. The Whitlam Labor Government was obviously the sitting executive. The governor-general and Parliamentary Coalition were clearly elites within the state apparatus.

The most contentious element is the legality of Sir John Kerr’s actions, and the actions of those around him. The reality is that the lines between politics and legality blur at this level of constitutional law. But nonetheless, it is difficult to argue that Australia has a democratic form of representative government and that the governor-general’s actions were legal. Only the most diehard monarchists would still assert that a governor-general can use “reserve powers” to sack a government that holds a working majority in the House of Representatives.

Australian Constitutional law is, of course, complicated and contentious. It encompasses not just the written document, but also the numerous conventions and norms the document implies. One such convention is that the governor-general may act only on the advice of appointed ministers in a government holding a working majority in the House of Representatives. If a governor-general can ignore the ministers, or decide not to act on their advice, the whole representative system becomes meaningless and effectively makes Australia a monarchical system, rather than a representative government.

The solicitor-general at the time, Sir Maurice Byers, sums up the illogicality of the so-called “reserve powers” Kerr invoked; “The reserve powers are a fiction. You can’t have an autocratic power which is destructive of the granted authority to the people. They just can’t co-exist. Therefore you can’t have a reserve power because you are saying the governor-general can override the people’s choice… and that’s a nonsense.” The last time this happened in Britain was 1834, and it’s fairly ludicrous to argue the monarch’s representative has powers greater than the monarch they represent (Jenny Hocking’s The Palace Letters discusses this at length).

At the same time, the speaker of the House of Representatives was prevented from seeing Kerr in order to officially notify him that Malcolm Fraser did not have a majority in the House of Representatives and therefore could not continue to be prime minister. Even if you believe it’s lawful for a governor-general to sack an elected government, it certainly isn’t lawful to maintain a Government that has been explicitly rejected by the House of Representatives. The 11th of November 1975 was certainly a soft coup, without violence, but a coup nonetheless.

For just over a month, Australia was governed by a prime minister with no democratic legitimacy who seized power by illegal means. Fraser did not command a majority in the House of Representatives. His only claim to lead the country came from royal favour through the governor-general. That voters later elected him does not change the fact he first gained power in a coup. There are multiple examples of coups and coup attempts later being democratically ratified: Portugal in 1974, Venezuela in 1997 and the US in 2024. None of these subsequent elections change the facts of the previous attempts to oust governments.

The failure to accurately name the events of 1975 is part of a much broader tendency to gloss over, obfuscate, or outright misrepresent parts of our history that are difficult, uncomfortable and potentially threatening to the Australian elites. This is made clearest in the way we talk about colonisation and the treatment of Indigenous Australians. The policies of dispossession, massacres and separating families are not considered genocide by a great many Australians. To do so would threaten mining and agricultural interests by raising the spectre of reparations and a much broader native title regime, as well as a delegitimisation of Australian political structures. Glossing over the coup of 1975 represents a small example of this reflex.

Engaging with the events as an illegal seizure of power requires confronting the fact that there were powerful elites in Australia for whom democratic legitimacy was secondary to maintaining their power. This is both important and uncomfortable because those anti-democratic elements continue to flourish in Australian society. For Australia’s ownership class, retaining their economic holdings is significantly more important than the democratic legitimacy of any government. Similarly, for Australia’s national security and foreign policy elites, the maintenance of Australia’s place in the Western alliance system headed by the US absolutely trumps any notions of respecting the policies of a representative government. Arguably the Whitlam Government was only a minor threat to both; but much, much more of a threat than any other post-War government.

By treating the events of 1975 as a coup, Australians must also engage with the idea that Anglo-American nations are capable of having coups. Political violence, illegal and irregular seizures of power, and attempts at both are not at all foreign to Australia or other Western nations. Pre-Federation Australian history was marked by the Rum Rebellion of 1808, the Eureka Stockade in 1854, and countless massacres of Indigenous people in pursuit of land. During the Depression, the fascist organisation the New Guard came very close to an armed insurrection in New South Wales – averted only by a vice-regal intervention similar to the events of 1975. And in 1949 the Coal Miners’ strike was only broken by deploying the military. The US has had its share of coups, attempted coups and insurrections from the Lecompten pro-Slavery Government seizing power in Kansas in 1857 to the failed Business Plot of 1936, and, of course, the events of January 6, 2021.

Despite this history, in Australia coups are generally treated as a phenomenon of black and brown nations; they occur in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and occasionally continental Europe. It fits well with the mainstream narrative of a peaceful founding and slow, steady progress achieved through representative institutions. The government ads at the centenary of Federation in 2001 are a perfect example of this. The ads posit that Australians don’t know about Federation “because in 1901 our nation was created with a vote, not a war". This, of course, ignores the Frontier Wars dispossessing Aboriginal people that were required to establish the nation, and that it was very much active in 1901. In relation to 1975, until recently, the Museum of Australian Democracy calls the last stage of their exhibit “The People Decide”, which at the very least obscures the blatantly anti-democratic nature of the events.

Why does this matter? Why should we care about how we refer to the events of 1975? Why talk about it now? By treating the ouster of the Whitlam Government as a singular, strange, quirky event we buy into a pleasant fantasy about our country; that we are somehow especially democratic and not susceptible to forces that are happy to dispense with representative government. In contrast, by examining 1975 as a coup, we can better identify the interests that benefitted from Whitlam’s ousting and examine their standing today. We can better understand that threats to representative government in Australia are not external, foreign forces, but come from within Australian society. We also get a sense of how to react and how not to react to anti-democratic actions. For example, there are notable parallels between Whitlam’s “Shame, Fraser, Shame” campaign and the Democrats’ focus on Trump’s threat to democracy after 6 January. Like the Democrats, Whitlam was obsessed with rules and norms, even when it was manifestly clear the other side had thrown out the rule book. In his own account of 1975 Whitlam states;

When I spoke to the caucus and in talks with party officials, I stressed and they all completely agreed that we should not depart from the accepted processes. We had won the 1972 and 1974 elections in accordance with the rules. We should strive to win again in accordance with the rules. The Liberals in the state parliaments, in the Senate, in Government House, on the High Court had done enough damage to Australia’s institutions and principles: we would not compound that damage.

In both instances this strategy obviously failed. It emphasises the inherent goodness of democracy, rather than the benefits voters gain from it. This is especially important at a time when democratic institutions are facing a crisis of legitimacy.

Calling the fall of the Whitlam Government a coup is not a new idea. Whitlam himself called it a coup. Paul Keating has called it a coup. Multiple journalists and commentators have done so, along with a section of the political left. However, the notion that 1975 was a coup has not been treated seriously by mainstream media or commentators. On this 50-year anniversary there will likely be numerous talks, events, TV, streaming, radio and podcasts about the events that took place. I hope Australians can at least start a serious discussion about the 1975 coup, especially at a time when we are confronting rising authoritarian tendencies in the West.

Read more about the Dismissal at 50.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.