Ambush and deceit

November 4, 2025

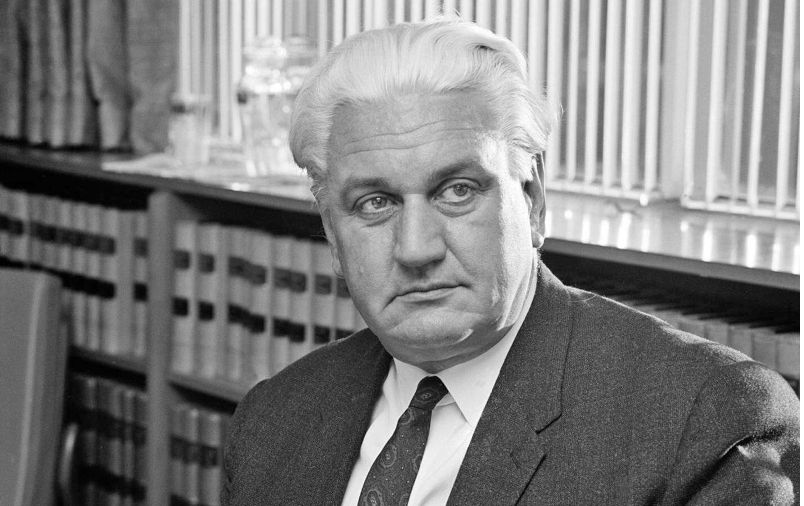

The first in a series of first-hand accounts of the Dismissal, from the man who was there: John Menadue.

Deceit is the one word that comes to mind when I think about the Dismissal.

Many in the Coalition, with a born-to-rule view after 23 years of conservative rule, believed that the election of the Whitlam Government in 1972 was an aberration.

More bills were defeated in the Senate in the three years of the Whitlam Government than in the previous 72 years.

There was a dry run for a dismissal in 1974. There was much speculation then that the Coalition led by Bill Sneddon would block supply. Fortunately, governor-general Hasluck accepted Whitlam’s advice for a double dissolution and, with his help, the Senate agreed to allow supply. The Hasluck model was clear. But governor-general Sir John Kerr did not follow the Hasluck model in 1975. Instead, he sacked his prime minister.

But for a foretaste of what was to come we must go back to December 1972 when Senator Withers, the leader of the Liberals in the Senate, denied the legitimacy of the newly elected Whitlam Government. Withers threatened that, “The Senate may be called upon to protect the national interest by exercising its undoubted constitutional power.” He said that the election mandate was “dishonest”, that Whitlam’s election was a “temporary electoral insanity“ and claimed that “the government following the will of the people would be a dangerous precedent for a democratic country”.

After the Dismissal, Withers said, “for all I know my blokes might have collapsed on the 12th. I don’t know. You just hope day after day you would get through until the adjournment… There were two senators who told me they were prepared to go. I reckon we had another week. If I had got through that week, then you would look at the following week. I would have lost them sometime after 20 November onwards. I know I would have lost them in the run-up to 30 November, but it wouldn’t have been two then, it would have been ten.”

Kerr intervened prematurely in a political contest which saved Malcolm Fraser but greatly damaged Gough Whitlam.

We also now know, through Jenny Hocking’s research, that there were five Liberal Senators who had decided a week before the Dismissal that they would abstain on any future bill to defer supply. That would allow supply to pass. While searching through Senator Missen’s records, Hocking found clear evidence that five Liberal Senators were prepared to allow supply, not by supporting it, but by not voting to defer Supply. They would abstain.

“Senator Missen’s diary vindicates the view that a political solution to the crisis was at hand and that the Senate was about to ‘break’ and refutes the historical claims of both Fraser and Kerr that the Senate would never have passed supply. Missen recounts that he, together with four fellow dissident Liberal senators — Jessop, Bessell, Laucke, and Bonner — had made a pact, just days before the Dismissal. Missen writes, in his entry for the week ending 3 November 1975, that “a bleak position” for the Opposition had developed, and if ‘it was a choice between voting for or against the Budget Bills, we would all abstain and allow the Budget to pass’. The five rebels had ‘quietly reached this resolution on the Tuesday’ – that is, one week before the dismissal… This agreement would have had critical consequences for Whitlam’s decision to call the half-Senate election, had that election been granted contingent on the passage of supply.”

In addition, the late David Smith, the official secretary to the governor-general, had told us that if Whitlam had not gone to the governor-general to recommend a half-Senate election, the events of 11 November simply would not have occurred.

It was a courtesy of Whitlam to tell the governor-general in advance what he was coming to see him about. This enabled Kerr to set the trap by ensuring that he dismissed the Whitlam Government before the prime minister could recommend a half-Senate election.

The governor-general would have been duty bound to accept the advice of the prime minister for an election. But Kerr beat him to the punch by sacking him first.

Whitlam was within a whisker of victory on 11 November, but little did he know it at the time.

Even before the Dismissal and breaking of conventions developed over centuries that upper houses should not block money bills, we had a breach of the well-established convention in Australia that on retirement or death of a senator he/she would be replaced by a person from the same party. With the appointment of Senator Murphy to the High Court, the government expected that the NSW premier would support a Labor Senator to replace him. That did not occur. That breach of convention was followed later that year and with very serious consequences. Labor Senator Bert Milliner from Queensland died. But Joh Bjelke-Petersen appointed a stooge, Pat Field, to replace Milner. Field was a Labor renegade who voted consistently with the Coalition when he was appointed to the Senate. But for that breach of convention, the Coalition would never have been able to defer supply. Milner’s death gave Fraser the extra vote he needed.

One other convention that we thought was critical was the separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary. There was a serious breach of this convention.

In March 1975, Kerr approached the vice-chancellor of the Australian National University with an unusual proposition: the formation of a group within the university that could, in confidence and without the knowledge of the prime minister, advise on the nature and extent of the powers of the governor-general. Included in that tutorial group was a very senior judicial figure, Sir Anthony Mason, a sitting justice of the High Court.

Kerr spoke of Mason as “fortifying me for the action I was to take" and that Mason was “a critical part in my thinking”. Mason even drafted a letter of dismissal but which Kerr did not use. Mason did not divulge any of this to his fellow High Court justices.

Mason told Kerr that he disagreed with the advice of the solicitor-general, Maurice Byers, that the reserve power had fallen into disuse.

Byers had been quite emphatic. “The reserve power can’t exist (because) you can’t have an autocratic power which is destructive of the granted authority of the people. They just can’t co-exist. Therefore, you can’t have a reserve power because you are saying ‘the governor-general can override the people’s choice’… And that is nonsense…Reserve powers are nonsense."

We also learned later that the Queen’s private secretary told Kerr that he had the power to dismiss the Whitlam Government and that it would do no harm to the Palace in doing so, but, in fact, would do the Palace some good.

Ellicott, the shadow attorney-general, produced an opinion which he widely circulated on 16 October, that the governor-general should dismiss the government. To Whitlam, Kerr described the opinion as “bullshit”. In the department, we received a colourful briefing from Whitlam on what Kerr thought of Ellicott’s opinion.

But Mason, and later chief justice Barwick, assured Kerr that the divine right of kings was still alive, and he could sack the people’s choice. They were not neutral judges of our highest court. They were partisan political operators.

Kerr “was particularly concerned that the High Court on 24 June 1975, with reasons given on 30 September 1975, had decided that, in the view of the majority (Barwick, Gibbs, Stephen and Mason), governor-general Hasluck should not have granted a double dissolution in April 1974, in respect of the Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill". Kerr was concerned about the implications of the PMA decision in the use of the Crown discretion which would be necessary to dismiss a government.

That is why Kerr went and saw Barwick on 10 November, to make sure the latter would support his proposed action against the government. He was lobbying the High Court in advance.

As we know, Barwick, quite improperly, expressed his opinion supporting the proposed dismissal of the Whitlam Government to justices Stephen and Mason because Kerr was concerned that these two High Court justices had moved away from Barwick in two other cases, the Senate (Representation of Territories) Act and the Australian Assistance Plan Act. Barwick was confident Gibbs would support him.

Mason did, however, tell Kerr that if he was considering dismissing the prime minister, he should warn him in advance. Kerr never did that. Mason also told Kerr that, even if there was a risk that Whitlam might sack him, it was a risk he should be prepared to take.

It is interesting to speculate what the electoral outcome might have been in an election for both houses had Whitlam gone to the election with all the advantages of incumbency. Opinion polls showed there was a substantial swing to the government because of the actions of the Coalition in blocking supply.

Mason was concerned about his role. He wrote to Kerr, “I have felt some difficulty in my participation in the discussions, for it may appear to some that we are engaged in the consideration of important questions which may sooner or later come before the High Court for decision. No doubt, the questions which you have in mind are presently hypothetical. Unfortunately, the hypothetical questions of today have a distressing habit of becoming the actual questions of tomorrow. I, therefore, doubt whether it would be proper for me to become a member of the group on a continuing basis.”

In retrospect, Whitlam and many others, including me, were overconfident about securing supply.

Cabinet discussed attaching a clause to the supply bills to ensure that they came back to the House of Representatives before going to the governor-general for assent. The Cabinet was of the view, however, that this was unnecessary and could be counterproductive in antagonising the Senate.

I also suggested to Whitlam that I travel to London to brief John Bunting, our High Commissioner there, who was the secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet before me. The visit would be to ensure that the Palace was properly briefed in case the prime minister had to act quickly for the dismissal of the governor-general. Whitlam said that would not be necessary.

We also suggested the prime minister might invite the governor-general to address the Senate or perhaps both Houses of Parliament, urging the passage of the supply bills. My note of 11 December 1975 referred to many suggestions made by the department about how advice should be given to the governor-general, including letters to him setting out the government’s position.

The advice given by Whitlam to the governor-general was oral, in the expectation that the Opposition would give way.

The prime minister did not believe it was correct to involve the governor-general in such political enterprises. In retrospect, it might have flushed out the governor-general, but Whitlam was always very conscious of the proper role of the governor-general and that he should not involve him politically.

In mid-1975, Kerr told Whitlam that he would be prepared to sign appropriation bills on the advice of his ministers even if they had not been passed by the Senate. Whitlam told Kerr that he would not be prepared to advise this course because he was sure that if the governor-general did sign such bills, a challenge in the High Court was certain, and the government would lose. This could precipitate a general election, and the government would be forced to campaign in an election on what would be widely interpreted as an illegal act. This offer was made by Kerr. It was not proposed by Whitlam. This confirmed in Whitlam’s mind more than anything else that Kerr was supportive of the government. That was also my interpretation. How naïve we were!

Kerr must have been shaken by action which Whitlam took against Queensland governor Hannah. The practice was that the senior governor held a “dormant commission” and became the administrator of the Commonwealth in the absence of the governor-general. Hannah was the senior state governor.

He had made his speech at a long lunch on 15 October which was extremely hostile to the Whitlam Government. He had caught the Bjelke-Petersen infection. Whitlam decided immediately that Hannah’s dormant commission should be withdrawn so that he could not become the administrator in the governor-general’s absence.

At Whitlam’s direction, we drafted a letter in the department to sign to go to Buckingham Palace via Kerr, terminating Hannah’s dormant commission. Kerr received the letter but decided that the letter should go direct from the prime minister to Buckingham Palace.

It was sent on 17 October and Hannah’s dormant commission was terminated on 26 October. That action clearly put Kerr on notice that a similar fate might befall him. The mechanics and time delay in Whitlam sacking Kerr in a crisis made that a most unlikely possibility. It may not have been in Whitlam’s mind, but it would certainly have preyed on Kerr’s mind.

At a dinner at Government House for the Malaysian prime minister on 16 October, Whitlam said in a joking, but not very sensitive, way that “it could be a race between me getting to the Queen to get you dismissed and you terminating my commission as prime minister". I am told that everyone laughed, but Kerr must have seen the danger.

The evidence is overwhelming that Kerr was obsessed about losing his job. As journalist Paul Kelly put it in power terms, “Kerr had decided to dismiss Whitlam before Whitlam had a chance to dismiss him. It was elemental, that primitive. But Kerr sought a loftier motive than merely saving his own job. His justification was to preserve the reputation and importance of the Crown.”

Certain of Kerr’s obsession about Whitlam dismissing him, Fraser piled on the pressure even more. According to Kelly, on 6 November in what Fraser described as his “most important meeting with the governor-general", Fraser said: “I now told the governor-general that if Australia did not get an election, the Opposition would have no choice but to be highly critical of him. We would have to say he’d failed his duty to the nation."

Fraser knew Kerr’s weakness better than the prime minister. He was threatening the governor-general.

The 11 November was a day I will never forget. I was working for Whitlam in the morning and Fraser in the afternoon.

I attended an early meeting in the prime minister’s office with Whitlam, Fred Daly, Frank Crean, Malcolm Fraser, Phil Lynch and Doug Anthony. It was designed to see if some resolution of the impasse over supply was possible. It became clear that a solution was not at hand.

But before the meeting, and not known to the prime minister or me, I learned that Fraser had earlier been in touch with Frank Ley, the Chief Electoral Commissioner. Ley was concerned and asked me to inform the prime minister. I made a note: “The advice given to Fraser, which he conveyed to me, was that any decision on a pre-Christmas election had to be made quickly, perhaps that day or early next week at the latest. This was obviously very valuable advice for Fraser. I passed this information from Ley to the prime minister.”

After that meeting, I contacted Kerr’s office to make an appointment for the prime minister to see the governor-general concerning the half-Senate election. The time proposed was not convenient for Kerr. Clearly, the timing of the coup was underway, but little did I expect it.

There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing on the timing until the prime minister rang Kerr directly and made an appointment.

Meetings at Government House that day were carefully arranged with Fraser hiding in one of the backrooms while waiting for the nod that Whitlam had been sacked and he would be asked to form a government

I continued in the department, helping prepare papers for the half-Senate election which would involve the states issuing writs. I gave the papers to the prime minister and awaited his return from Government House to put in process arrangements for the election.

Then the bombshell dropped

David Smith, the official secretary at Government House, rang and told me that the Whitlam Government had been dismissed. I must have gone onto autopilot for a while. There were things that had to be done.

I informed Geoff Yeend, my deputy, Alan Cooley, the head of the Public Service Board, and Fred Wheeler, the secretary of Treasury.

Whitlam’s driver then rang me and told me that “the boss” wanted to see me urgently. I drove immediately to the Lodge. Gough was at the table eating a steak. He said, “Comrade, the bastard Kerr has done a Game on me.” In the 1930s, governor Game had dismissed the NSW Lang Labor Government. Gough asked me to call the secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department. I was overcoming my shock; I told Gough that it would not be appropriate to call public servants but that he should call Kep Enderby, who was the previous attorney-general. Several other ex-ministers came and there was discussion on what Whitlam and the Labor caucus should do.

I received a telephone call from my personal secretary Elaine Miller that Fraser wanted to see me. I told her to tell Fraser that she couldn’t find me. She rang about 10 minutes later and said, “the prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, wants to see you urgently”. I decided that I should leave the meeting with Whitlam and go to Parliament House to meet Fraser in his office. I often wondered afterwards whether I should have explained better to Whitlam my departure from the Lodge.

Not surprisingly, there was a lot of noise and activity in Fraser’s office when I got there. I agreed to continue as secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet, at least in the caretaker period.,

We set in motion the necessary election arrangements, preparations for the swearing in of new ministers the next day and the first Fraser Government Cabinet meeting. And a lot more I can’t recall!

At the end of the day, Fraser, my new boss, asked me to join him for drinks at the Commonwealth Club of which I was not a member by choice. I had a glass of red wine but declined an invitation for dinner.

I limped home for consolation with my family.

After the dismissal of the government, Kerr was concerned that the speaker of the House of Representatives was at his gate at Yarralumla, seeking to see him to convey a message that the House of Representatives had passed a motion calling for the dismissal of the new Fraser Government and that the governor-general should reinstall the Whitlam Government. With supply passed and with the speaker at his gate, Kerr was disturbed. He spoke to Mason again for advice. Mason told Kerr that he need not see the speaker. That was extraordinary.

This was the second dismissal of the day.

It was OK for Kerr to deceive his prime minister but it was not OK to deceive the leader of the Opposition who had just lost a vote of confidence in the House of Representatives.

The next day, when I was at Government House for the swearing-in of the new Fraser ministry, Kerr told the new ministers that he had considered whether he should see the speaker the day before but “having committed myself to a certain course of action I could not go back”. That was extraordinary, refusing to see the speaker.

King Charles I had been executed for defying the speaker and the House of Commons.

Tomorrow: The second dismissal – the loans affair and meetings with Kerr