Axed AG tells how Labor really changes the Constitution

November 25, 2025

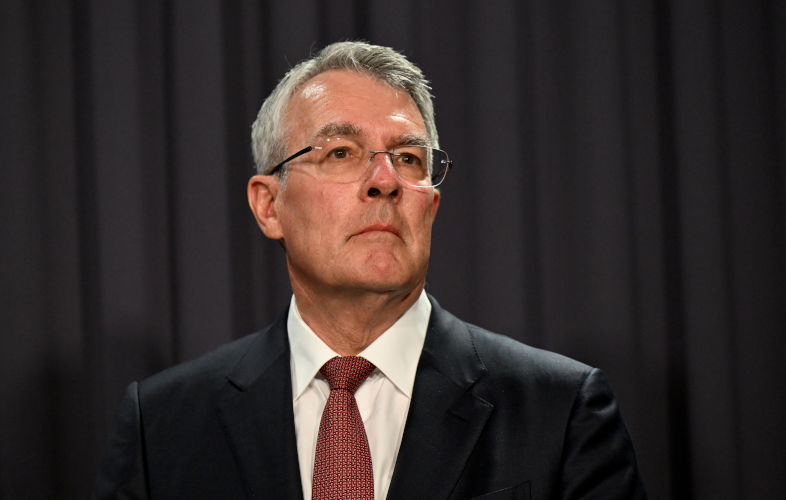

Despite Labor’s longstanding appetite for constitutional reform, former Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus now points to a different path: bold, nation-shaping change without the need for a referendum.

The notion of Constitution reform is not dead within the current Labor Government, but, even with a burst of enthusiasm from the 50th anniversary of the dismissal of Gough Whitlam, it won’t be controversial and it won’t be quick.

That was the takeout from the very thoughtful 2025 Geoffrey Sawer Lecture given on 20 November at the Australian National University by recently axed attorney-general Mark Dreyfus.

Dumped from the ministry by colleagues with a fraction of his capacities after this year’s election, Dreyfus outlined three major changes he wanted, none of them ground-breaking.

- Fixed four-year terms of Parliament, which has been Labor policy since before it was rejected at referendum under the Hawke Government in 1988. Dreyfus noted that John Howard, Opposition Leader at the time, had, just last week, supported the call, saying “It’s ludicrous you’ve got four-year terms in all the states but the national parliament doesn’t. It’s just crazy.”

- Becoming a republic, Dreyfus noting much change in the nation since the “grievous disappointment” of the 1999 referendum. He noted that “we might also tend to the matter of so-called reserve powers and provide our Head of State, to use Whitlam’s words, ‘no powers anterior or superior’ to those expressed in our amended Constitution”.

- A constitutional commission, perhaps operating on lines similar to the Australian Law Reform Commission, but of which there have already been various iterations over the decades.

But it was away from the difficult, formal (Section 128) constitutional changes that Dreyfus was most interesting, speaking of “a parallel Labor tradition of pursuing nation-building ambitions notwithstanding constitutional limitations on the national government.”

Labor, he said, had and could work “creatively” within the constraints of the written Constitution and be seen to be “pushing at its boundaries”.

He noted the High Court’s development of the implied freedom of political communication, including his having been junior counsel in two relevant matters.

But he drew also from Sawer himself, not just his famous line from 1967 about Australian being, constitutionally, the “frozen continent”, but going on to recall the celebrated Professor’s enjoinder:

“Hence it is likely that more than ever the constructive development of Australian federalism depends on the politicians and civil servants, exercising the instruments of federal persuasion or coercion and the techniques of co-operative federalism. They may have to rely increasingly on the evasion of constitutional obstacles…”

Dreyfus talked about Labor’s nation-building without formal constitutional change, from Prime Minister Andrew Fisher’s pursuit of transcontinental railways and establishment of the Commonwealth Bank to the Albanese Government using “the full stretch of its constitutional authority” to implement its housing program.

But his best example of change sans referendum was the landmark Tasmanian Dams case of 1983, run under Attorney-General Gareth Evans and drawing on manifold heads of constitutional power.

Dreyfus told his sizeable audience at the ANU, “The Act was drafted in a ‘belt and braces’ manner to attract whatever bases of constitutional support were available. Perhaps the better term is ‘kitchen sink’.”

He quoted Evans’s memoirs: “Drafting that legislation … was about as much fun as a constitutional lawyer could ever have sitting down. We threw every weapon in the armoury at it, with three separate sets of provisions prohibiting essentially the same activity, based respectively on the external affairs power, the corporations power, and - in relation to sites ‘of particular significance to the people of the Aboriginal race’—the section 51(xxvi) race power.”

Unsurprisingly, given the timing of his address, Dreyfus dwelt for some time on the Dismissal, and it was here that his methodical approach gave way to a little more fire.

He gave the mandatory outline of where he had been on the day: in a law exam in the Exhibition Building when a student’s representative had burst in with a megaphone urging immediate protest: “I’d like to tell you we threw down our pens and ran to the square. We did not. We finished our law exam.”

But he did join later and his rage was still palpable in the Sawer lecture.

“The office of the governor-general [whom he elsewhere described as ‘gormless’] was irreparably harmed,” he said.

“The Fraser government was permanently tainted.

“Our democracy was stained.

“Subsequent revelations have cast a shadow over the High Court and the Palace.”

His remedies were direct. Governor-general John Kerr should have warned Whitlam of his intention to dismiss him – a view that even Malcolm Fraser came to in later life. That probably would have put a stop to the nonsense.

Kerr should have informed House of Representatives Speaker Gordon Scholes and Senate President Justin O’Byrne. That probably would have led to Whitlam going to any subsequent election as prime minister.

And Kerr should have acknowledged the resolution of the House expressing confidence in Whitlam and acted in accordance with the democratic demands of the House.

Dreyfus had some time for sport as well, monstering former Liberal Attorney-General George Brandis’s attempts to draw parallels with opposition leader Whitlam’s threats to “destroy” the Gorton Government by voting against the 1970 Budget, which Brandis had claimed “was a much more aggressive use of Senate power than anything that happened in 1975”.

What Brandis’s version of course omitted to mention was that Labor was then in minority in both Houses and the vote was symbolic only.

In 1975, the Senate had been stacked by the appointment of the Bjelke-Petersen stooge Pat Field to a casual vacancy after the death of Labor’s Bert Milliner, allowing the Coalition to frustrate Supply and cause the crisis that allowed Fraser, in the words of Liberal Movement Senator Steele Hall, to come to power over a dead man’s corpse.

The disgrace of that perverse appointment by a corrupt state premier was fixed – by a referendum sponsored by Fraser himself – as soon as 1977. That referendum provided that casual vacancies must be filled by the nominee of the party whose senator had held the seat.

And that - 48 years ago next month - was the last time we on this “frozen continent” were moved to amend our Constitution.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.

Please donate to Pearls and Irritations

Help us to continue to bridge the gap on the global and local stories not covered in Australia’s mainstream media.