Death by plastic

November 4, 2025

“Mummy…Daddy, what are clouds made of?” Almost every parent has fielded the innocent, eager question, perhaps explaining about mist, fog, water vapour, raindrops. Today, if you said that, you’d be wrong.

Instead, you can inform your kids: “Clouds today are also made of polyethylene, polypropylene, polyethylene terephthalate, polymethyl methacrylate, polyamide 6, polycarbonate, ethylene-propylene copolymer, polyurethane and epoxy resin.”

In other words, clouds are full of toxic human trash.

That’s the word from a team of Japanese scientists who found that every litre of cloud they studied contains 7-15 plastic microparticles, tiny pieces of petrochemical junk measuring from 7-94 microns, which is generally less than the thickness of a human hair.

But then so does your brain. So does your blood and your heart, your liver and your kidneys. And so does your newborn baby and the breast milk it imbibes.

Next time you stir your coffee with a plastic spoon, just weigh that spoon in your hand: it’s about 7 grammes. That’s how much plastic medical researchers think is probably in your brain right now. So those are not entirely your own thoughts you are having – they are in part mediated by the emissions of the US$700 billion global petrochemical industry. They are strongly linked to dementia, low IQ, inability to reason and other brain conditions clearly on the rise.

Of course, you didn’t want to know that, so like about eight billion other people, you look the other way, keep on using plastics, wearing microfibre and synthetic clothing, buying drinks in plastic bottles and plastic toys for your kids, storing food in plastic containers, driving cars and flying in planes made of plastic, furnishing your home and office in plastic. If someone told you it contained arsenic, you might pause – but nah. It’s just plastic. Must be safe, mustn’t it? Those big chemical corporates would never sell it if it wasn’t safe, would they?

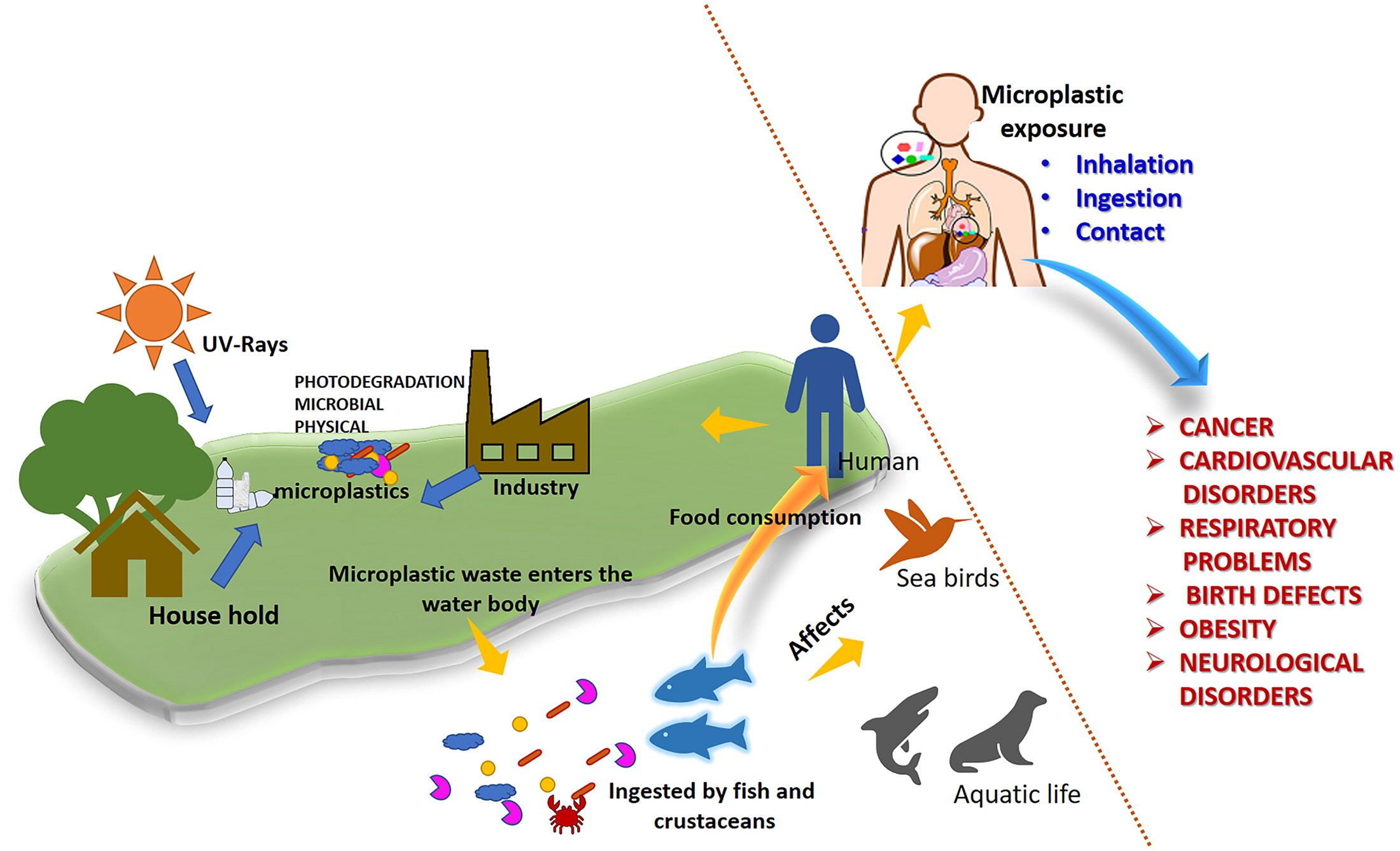

Micro- and nanoplastics are now everywhere. They are regularly detected in food, farmland, seawater, drinking water, fish, snow, cosmetics and city air. Plastics have been found in the deepest parts of the oceans, on the remotest islands and in the highest mountains.

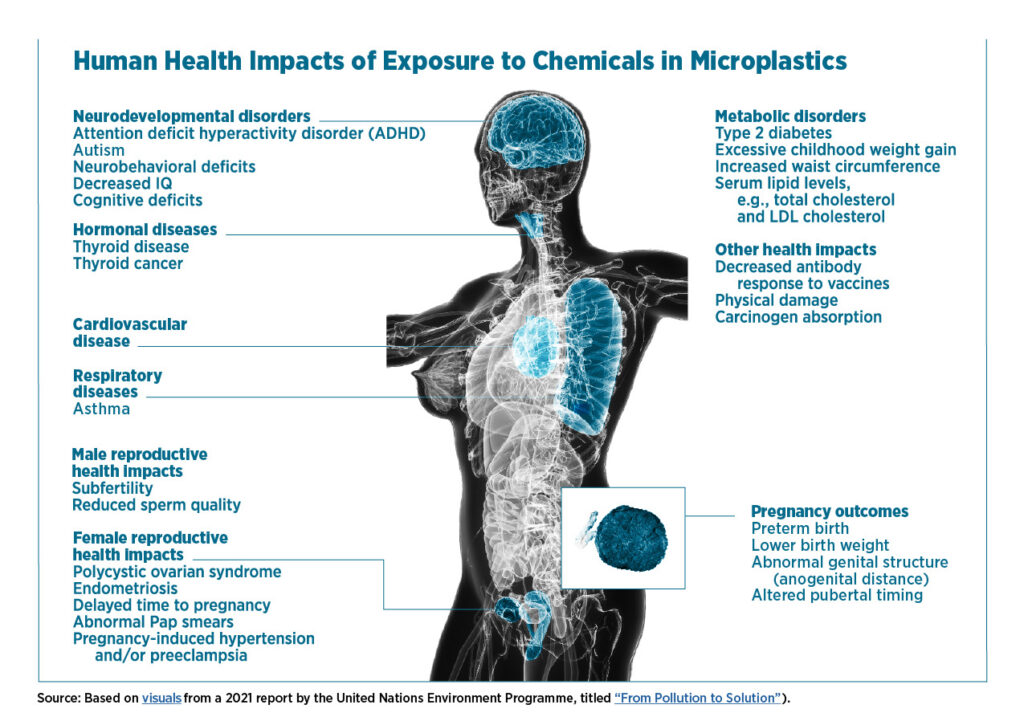

The medical consensus is that these invisible pollutants pose a rising danger to human health – as well as all other animals and plants on the planet. A burgeoning body of hard evidence now links micro- and nanoplastic particles with cancer, inflammatory disease, impaired immunity, tissue degeneration, heart disease, birth defects, diabetes, hormonal problems like obesity and infertility, and many more, as the following UNEP diagram indicates.

World plastics production rose from 234 million tonnes in 2000 to 435 million tonnes a year in 2020. It is on track to reach 740 million tonnes a year by 2040 and 1.2 billion tonnes by 2060. There are more than 13,000 different plastic chemicals. Over time, and with exposure to sunlight, erosion and microbes, all this plastic is ground down into microscopic particles and nanoparticles which can travel almost anywhere in the environment and enter any part of your body. And they can transport a lot of other nasties with them.

Figure 1. The plastics cycle: you are now part of it.

Thirteen thousand plastic chemicals sounds a lot – but it is in fact less that 4% of the world’s total industrial chemical inventory, barely one third of the tip of the iceberg. So plastics, like climate change, while they garner a lot of headlines (and not much action) are only a small facet of a very much larger, Earthwide problem: the metacrisis or compound human emergency.

Put another way, total human chemical emissions are estimated at around 220 billion tonnes a year, cumulatively. Of that total, plastics make up only about 0.2% by weight, which does not sound much. However, plastics are far more reactive and dangerous than, say, eroded topsoil – and thus make up a very much larger share of the global toxic load which is hard to measure. Plus, the evidence suggests that they never go away, but keep on accumulating in our living environment and our bodies, doing ever more damage until all humans are forever plasticised and contaminated.

More seriously still, scientists now suspect plastic microparticles can mess with your genes, poisoning or fragmenting them and altering the vital roles they perform to keep you alive (expression). They can also trigger “bad genes” that cause inflammation. This applies not only to humans but to all animals and plants, and may emerge as a vital factor in the current wave of extinctions.

The solution to the plastics crisis is, conveniently, the same as the solution to the climate crisis: end all extraction and use of fossil fuels. This win-win would not only slow and reverse global heating, but also eliminate the primary source of toxins in the human living environment.

However, the evidence is clear that the nations and corporates who make their money from fossil fuels will refuse to abandon their highly profitable, but destructive, behaviour. In short, they do not care how many people, especially children, they kill in pursuit of profit.

A second, far slower, option is to try to identify which particular plastics or chemicals cause the worst effects – and then ban them. However, of the 2000+ new chemicals released onto world markets every year, very few have ever been tested for human or environmental safety. The chemical companies will argue that testing is too expensive, but in reality they prefer to make quick profits on new products before the resulting death and injury toll becomes undeniable and a ban possible – a process that takes decades.

This is illustrated in the case of the chemical weedkiller glyphosate, first released in 1974, suspected of causing cancer in 2000, classified as a probable carcinogen by WHO in 2015, and still in widespread use today, despite numerous legal attempts to ban it in many countries.

Testing all 350,000 chemicals in the current industrial inventory is not only impractical, it would probably take the better part of a million years. At present the law in most countries requires the government to prove a chemical is dangerous – rather than the manufacturers to prove it is safe. Plastics are no different.

According to the World Health Organisation, around 14 million people die each year from chemicals in the human living environment – 24% of the human population. This is unarguably the worst case of manslaughter in history, double the death toll of World War II. Yet no government or nation is doing anything substantive to prevent it.

Plastics are a part of this toll, but a part that is set to redouble as our use of these deadly substances grows. It is a fresh case of how civilisation intends to die by its own hand.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.