Environment: Six strategies will simultaneously reduce emissions and help communities prepare

November 2, 2025

Six broad strategies will tackle the root causes of climate change and help groups prepare for the consequences of global warming. Environmentally sustainable aircraft are slow to take off. Local governments can take a lead in promoting biodiversity.

Six policies to promote climate mitigation and adaptation

I can’t recall exactly when but let’s say 15 years ago, many people, including myself, were firm believers that the paramount climate task was mitigation: reducing the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. We thought that it was still possible to get on top of emissions rapidly. In public health-speak, we thought that effective prevention would avoid most of the need for harm reduction.

However, it soon became obvious that emissions were not going to fall rapidly and that the consequences were already with us, principally, but not only, in places and populations who had contributed the least to the problem. Calls for more attention to be directed to adaptation then increased and resources slowly flowed in that direction. Unfortunately, as adaptation is currently most needed by nations and people that are most at risk of suffering the consequences of climate change and least able to cope with them, it is often dependent on reluctant wealthier nations providing the required funds and expertise.

The World Resources Institute has examined more than 300 adaptation investments and found that over half are also likely to reduce emissions. In particular, just six climate strategies can reduce emissions in high-polluting sectors and help families and communities prepare for, and cope with, the threats of global warming:

- Expand decentralised renewable energy systems – as well as reducing emissions, local wind and solar farms that distribute energy to small, decentralised grids can avoid disruptions caused by energy generation and distribution problems further away and recover more quickly when local outages happen. Local systems not connected to a much wider grid can also provide energy to essential facilities and services when disasters hit.

- Promote sustainable agriculture and land use – agroforestry, rotational cropping, diversified crops, integration of trees with crops and livestock (silvopasture) and community-managed forests all reduce emissions, strengthen farmers’ resilience to climate change and protect local food supplies.

- Invest in climate-smart buildings – orienting windows towards the polar regions, painting roofs white, improving energy efficiency and using low-carbon building materials all reduce emissions and lower indoor temperatures to protect occupants and reduce the demand for air-conditioning.

- Improve mass transit – expanding the use of public transport to a third of all urban passenger trips saves emissions, improves the system’s safety and reliability and makes mass transport infrastructure better able to withstand climate risks. Using heat-reflective coatings on vehicles and planting trees along routes improves passenger comfort.

- Protect and restore coastal wetlands – expanding tidal marshes, mangrove forests and seagrass beds increases carbon storage, defends coasts and infrastructure from floods, improves water filtration and encourages marine biodiversity.

- Secure Indigenous land rights – Indigenous peoples and local communities manage almost half of the land on Earth, including many critical ecosystems, but their legal rights are seldom protected. Securing land tenure helps prevent emissions and empowers communities to pursue local nature-based solutions to climate problems.

None of the specific interventions is new, but the report helps authorities select the most cost-effective strategies.

In recent years, a third strand of action has received attention, the responsibility of those nations and companies most responsible for causing climate change to provide to countries and communities the funds needed to deal with the loss and damage that has already been caused by climate change. Wealthy nations have mostly clubbed together to avoid, rather than embrace, this responsibility.

Is your local government taking biodiversity conservation seriously?

Woollahra Council’s 12 square kilometres include well-known precincts such as Paddington, Double Bay, Watsons Bay and Vaucluse in Sydney’s generally affluent eastern suburbs. It lies adjacent to the Sydney City and Waverley Council areas, the latter containing many of Sydney’s famous ocean beaches. In general, Woollahra is quite highly urbanised and relatively densely populated.

Notwithstanding the unpromising-sounding environment, Woollahra has several kilometres of harbour shoreline, a few kilometres of ocean cliffs and several areas of remnant bushland containing species of threatened fauna (e.g. bats, owls and seahorses) and flora (e.g., wattles, she-oaks and bottle brushes). I live in Woollahra and have seen 45 species of birds immediately around our home.

It’s pleasing to see, then, that the protection and conservation of biodiversity is a priority for Woollahra Council. They have just released the second Biodiversity Conservation Strategy, covering the period 2025-2035. This complements the Council’s Urban Forest Strategy and Environmental Sustainability Action Plan.

I won’t try to describe the biodiversity strategy in detail. Suffice to say that it identifies locally threatened species and important habitats, describes the area’s threats to biodiversity (pretty much the same as everywhere) and provides a detailed action plan for remaining bushland, habitat corridors, freshwater, foreshore and marine ecosystems, and, crucially, working with communities to foster engagement. It also has some great photos.

Has your local council got a biodiversity conservation strategy? If not, why not give them a nudge?

Airlines will be carbon-intensive for a long time yet

Air travel contributes about 2.5% of current greenhouse gas emissions, but this jumps to 4% when the effects of contrails are included. The industry’s recent modest improvements in fuel efficiency are overwhelmed by increases in passenger numbers and emissions are expected to increase by almost 60% between now and 2050.

A few weeks ago, I highlighted the hopelessly slow rate at which airlines are adopting Sustainable Aviation Fuels, despite their professed enthusiasm for them. I suggested, however, that it may not matter as SAFs will probably have only a small, short-term role in making air travel more environmentally sustainable. Unsurprisingly, the industry’s rhetorical support for SAFs is not without purpose – it delays the development of more sustainable planes (rather than fuels) and helps to lock in the use of existing fossil fuel-based aircraft (both those already in service and those on the order books) for 20-30 years.

Assuming that flying people and goods around the world remains viable, the medium- and long-term solutions to aviation’s emissions problems are more likely to lie with new propulsion aircraft powered by electricity or hydrogen or a hybrid of both.

Electric aircraft are powered by fuel cells that generate power in-flight or batteries similar to but bigger than those used in EVs. Range is the major problem for battery-driven planes at present but two Chinese companies are planning to launch a plane capable of carrying up to 20 passengers over a range of 2000-3000 km in 2027/28. Longer ranges and a higher payload may be possible with planes fitted with fuel cells, although these may also produce contrails.

Hydrogen combustion in gas turbine engines, similar to those used on conventional aircraft, is more likely to provide the power for mid- and long-range flight. The small size of the hydrogen molecule and the large volumes that would be needed to power a plane present significant technical problems both in the plane and on the ground, not forgetting that the hydrogen would need to be produced sustainably.

Hybrid aircraft using gas turbines powered by hydrogen (or even conventional jet fuel in the short term) for taxiing and take-off and electricity at other times are also being considered.

All of the possible NPA solutions still require considerable development but neither the airlines nor the major manufacturers (basically Airbus and Boeing) are currently showing much interest. The development and rollout of NPA is, however, dependent on not just the airlines and plane-makers but also the active support of airports, investors, governments and even consumers. The inevitable delaying tactics of the current jet fuel suppliers will also be a factor.

Australia’s snake diversity

Australia has more than 200 species of snake, all playing essential roles in their ecosystems whether they be deserts, rainforests, mudflats or coastal waters.

The largest of Australia’s six families of snakes is the Elapidae with more than 100 species. The family includes all of our terrestrial venomous snakes (including taipans, death adders and brown, black, mulga and tiger snakes) and our sea snakes. The Inland Taipan is the world’s most venomous snake but fortunately is very reclusive.

More interesting Slytherinic facts:

- Some sea snakes can stay under water for up to two hours;

- There are 15 species of Pythonidae, most of which have heat-sensitive pits along their jaws which allow them to detect warm-blooded prey;

- The Colubridae family is the largest worldwide but Australia has only about 10 species;

- Freshwater Keelback Snakes can eat cane toads because they are resistant to the toad’s poison;

- We have more than 40 species of Typhlopidae or blind snakes which look like worms and spend most of their time underground.

In common with many other Australian animals, snakes are threatened by habitat loss, road mortality, persecution and invasive species.

If you are struggling to identify any or all of the snakes in the pictures, you can find their names in the linked file.

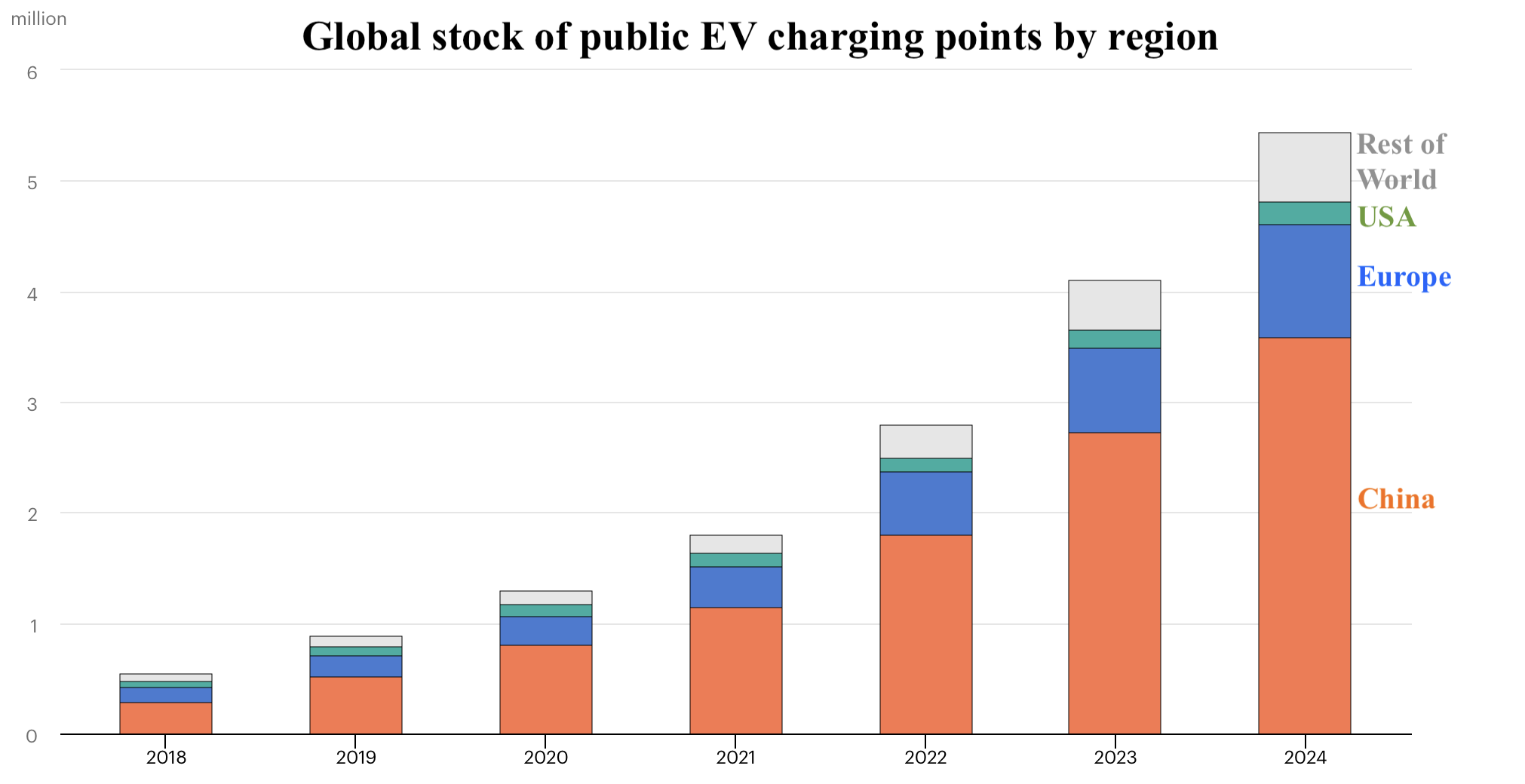

Public EV charging points increasing

In mid-2024, Australia had about 1850 individual high-power public EV chargers at more than 1000 locations.

No prizes for knowing which country has the most EV charging points, having secured a 12-fold increase from 280,000 in 2018 to 3.6 million in 2024. The US isn’t embracing EVs with the same enthusiasm, but numbers have increased from 60,000 to 200,000 in the same period.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.