‘Extraordinary and reprehensible circumstances' - Part 4

November 13, 2025

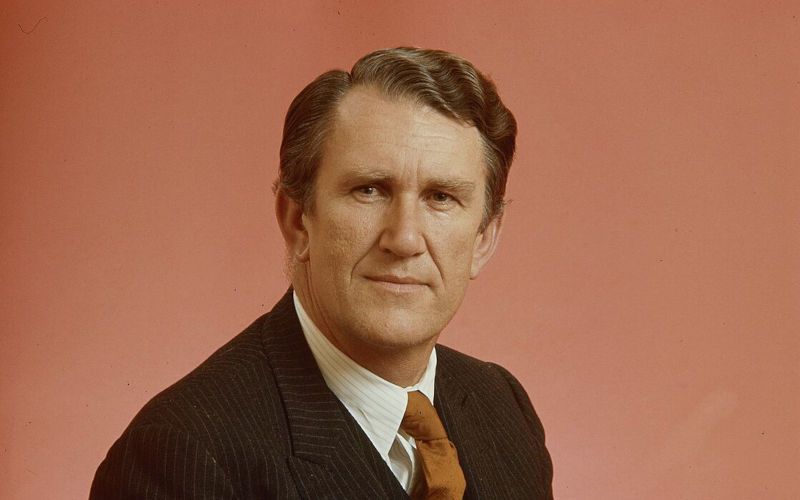

Malcolm Fraser was a conservative in terms of the constitution. His view was the Senate was “primarily a house of review – and apart from exceptional circumstances should not frustrate, certainly not on a purely obstructionist basis”

“I generally believe that if a government is elected to power and has the numbers and can maintain the numbers in the lower house it is entitled to expect that it will govern for the three-year term.” It is only “in the most extraordinary and reprehensible circumstances” that the opposition would seek “to use its numbers in the Senate to block supply”.

Malcolm Fraser, On becoming opposition leader, March 1975

Malcolm Fraser won a seat in Parliament in 1955, at the age of 25. Oxford-educated like his father, he said his main motivation for entering politics was his fundamental opposition to communism. He maintained he was no Tory, however; his wish was to engage in a liberal crusade to defeat communism in a battle of ideas. He agreed with many of the policy changes the Whitlam government made in office and, as prime minister, overturned very few of them.

Fraser exhibited an un-Australian hauteur and, as a wealthy grazier, there was something of the ‘born to rule’ manner about him. He was uncomfortable socially. His best friend at Oxford was an African and Fraser was a lifelong opponent of racism. In practical terms, he did more than Whitlam to end Australia’s White Australia immigration policy.

Fraser was a conservative in terms of the constitution. His view was “the Senate was ‘primarily a house of review – and apart from exceptional circumstances should not frustrate, certainly not on a purely obstructionist basis”. Yet once he discovered ‘exceptional and reprehensible circumstances’ to his satisfaction, Fraser would have no compunction about blocking supply. Having threatened to use the same tactic while in opposition five years earlier, Whitlam could seek no refuge in a moral argument.

Fraser’s opposition to the Whitlam government was based on two major factors. First, he believed that the sheer incompetence of Whitlam’s management of the Australian economy was driving it into the ground. In his eyes, the loans affair provided an egregious example of a maverick style of government.

Secondly, while Fraser agreed with some of Whitlam’s foreign policy initiatives, including on China, he was essentially a Cold War warrior and a strong supporter of the US alliance. He had been defence minister when Pine Gap came on stream and would have known much more than Whitlam about the critical purpose of the facilities and of their importance to the US relationship. Under Whitlam, as Curran wrote, “Australia’s formal, strategic relationship with America perched precariously on the edge of an abyss”. ANZUS seemed under threat.

Yet if Fraser tried to justify blocking supply on the basis of extraordinary circumstances in Australia’s relationship with the US and then took these issues to an election, he would have been on dangerous ground. While Australians overwhelmingly supported the ANZUS alliance, Whitlam could reassure them he did too. As the Watergate saga played out, President Nixon became less and less popular. There were signs the community wasn’t opposed to an Australian government displaying greater independence from the US. Fraser couldn’t talk about intelligence sharing; acknowledgement of the very existence of the Five Eyes was still decades away. He needed a convincing domestic policy issue on which to base the blocking of supply.

*****

If these realities complicated the situation for Malcolm Fraser, they created similar problems for the Americans. As suggested in Part 3 of this essay, Kissinger had likely adopted a ‘watch and wait’ strategy towards the Whitlam government in August 1974 while being ready to move into destabilisation mode as required. One sentence in the State Department top secret memorandum to Kissinger on 22 August proved to be rather prescient. “Given the opportunity to charge that the government has badly mishandled some major issue (more likely a domestic than a foreign policy one), the opposition might be able to line up the independents, who hold the balance in the Senate, and force new elections.”

In light of what happened, we can postulate that this may have been seen as one promising opportunity for US interference if the decision was taken to move against Whitlam. Such an approach would require a complex strategy, recognising the difficulty of orchestrating a change in government in a mature democracy. Such an approach seems consistent with former CIA officer Victor Marchetti’s view, who later said that covert US operations in Australia were like those in “Chile, but in a much more sophisticated and subtle form”.

The overriding condition for the operation was the need for absolute secrecy. In a telephone conversation between Nixon and Kissinger in September 1973, celebrating the overthrow of Allende, Nixon said, “as you know, our hand doesn’t show on this one”. In reply, Kissinger insisted “we didn’t do it. I mean we helped them. [Redacted] created the conditions as great as possible.” The same level of deniability was required in Australia. The most important foundation for such an operation in Australia was the appointment as US ambassador of Marshall Green, a career foreign service official still regarded as the most influential American head of mission ever to grace our shores. In those times when, as discussed in Part 3, US intervention in foreign countries’ governments was not exactly uncommon, it is possible that the White House wanted to prepare for a contingency in the future where they needed to destabilise the Australian government. After all, Australia had already been placed at number two on Nixon’s ‘shit list’ and, even by then, almost certainly satisfied the president’s criterion for intervention in Chile: “Let’s forget the pro-Communist. It was an anti-American government all the fucking way”.

There was certainly some concern in the ALP regarding Green’s curriculum vitae. In June 1974, denouncing Green as a “top US hatchet man”, Labor Senator Bill Brown claimed that “with few exceptions, wherever he has been posted or otherwise involved, there has been a bloodbath and/or a coup of some description”. Brown also warned Australians to be “ever vigilant to ensure our nation does not become another Chile”. While much vitriol descended on Brown’s unrepentant head and Bob Hawke called him an imbecile, Green had indeed served in countries, including South Korea and Indonesia, whose governments had changed during his term to the benefit of the US. Whether deserved or not, Green had acquired the nickname of the ‘Coupmaster’.

A decade after the dismissal, Clyde Cameron suggested that Green was sent to Australia because he was “a very skilled operative in the art of destabilisation of governments that the United States doesn’t approve of”. But destabilisation would only be necessary if Green failed in his main task, which was to persuade Whitlam to change his approach to the US and provide a guarantee the facilities were secure. Green got on well with Whitlam but ultimately, he was a seasoned professional with a single-minded commitment to pursuing US national interests. While Whitlam could be reassuring, he also blew hot and cold. Green could never elicit an ironclad guarantee about the facilities. He reported to Washington that Whitlam was a “whirling dervish”.

Nevertheless, in the early months of 1975, the Americans started to relax. As Green said in a meeting with Defense Secretary Schlesinger in Washington in February 1975, Whitlam “has gradually come to appreciate the importance of these installations not only to the US and Australia, but also to world peace. This was confirmed this week by Whitlam’s public and spirited defence of the U.S. presence.” Schlesinger, who at the August 1974 meeting had taken the hardest line against Australia, agreed. He believed the US facilities would be allowed to stay as long as Whitlam remained leader. Nevertheless, there were two concerns. The first was that Cairns took over as Prime Minister. The second concern was if Australia’s name came up during the current Congressional inquiries into the CIA.

Three months later, the situation had changed again. First, in March, Malcolm Fraser won the leadership of the Liberal party from Bill Snedden. Clearly, he was a much more dangerous opponent for Whitlam. Green would have known very well that all the US concerns about the facilities would disappear if Malcolm Fraser became prime minister. Secondly, a scandal had erupted over the ‘loans affair’, under which the Minister for Resources and Energy, Rex Connor, had been attempting to secure an enormous foreign loan without going through recognised channels. The whole affair made the government look inexperienced, incompetent and dishonest. Combined with continuing economic problems with both unemployment and inflation rising to record levels, the government’s popularity was in decline.

This all meant the electoral calculus had changed. If the opposition could force an election, their chances of winning had improved significantly.

Perhaps the main factor, however, was that an opportunity had emerged to remove Jim Cairns from the game. This was a task for the CIA and its smaller stable mate, Task Force 157. The redacted name in Kissinger’s conversation with Nixon over Chile was almost certainly that of Ted Shackley, who now headed the Agency’s East Asia Division covering Australia. Kissinger held Shackley in high regard and he thrived most of all during the CIA’s ‘Dark Period’. Shackley would control covert operations from Langley. On the ground, they would be run by Ed Wilson, formerly a colleague of Shackley’s in the CIA but now in Task Force 157. The team had recourse to a forger, Jim Flynn.

In June 1974, Cairns had become Deputy Prime Minister and was riding high. He was almost certainly next in line for the leadership. To coincide with Cairns’s promotion, his ASIO file was leaked to The Bulletin magazine. Among other things, ASIO characterised Cairns as an agent of leftist disruption, suggesting his policies were aimed at bringing about “anarchy and in due course, left-wing fascism”. The analysis was so trivial as to be absurd. It raised serious doubts not about Cairns, but rather the competence and politicisation of ASIO. But this was only a whiff of grapeshot. It had nothing to do with Cairns’s downfall a year later.

By then, Australia’s economy, like the rest of the world, was suffering from both rising inflation and rising unemployment. As Treasurer, Cairns, with a doctorate in Economics, had prime responsibility for economic management. But Senator John Button, who knew and admired Cairns, observed he “seemed strangely out of his depth”. His new younger lover, Junie Morosi, was running the Treasurer’s office and it was chaotic. Cairns, who seemed to operate in a strange, radiant state of grace, was becoming detached from reality. In his book on the press gallery, Rob Chalmers reported that when Whitlam’s press secretary asked the prime minister for his diagnosis of Cairns’s condition, his reply inclined more towards accuracy than elegance. “Comrade,” he declared gloomily, “he’s cunt-struck at 60.”

Cairns shared the government’s interest in securing a substantial foreign loan for resources development. As Treasurer, he agreed with his department’s strictures to avoid unconventional sources for raising the loans. He had consistently opposed paying any commission for such transactions. When Sir Robert Menzies, not a natural confrere of left-wing politicians, introduced Cairns to George Harris, president of the Carlton Football club, on the basis that Harris could act as intermediary for a $2b loan to the Australian government, what could possibly go wrong? Harris, whose principal calling was as a dentist, apparently had privileged access to vast sums of oil money from the middle east. Of course he did.

Those were innocent times. Ministers had their offices in the old Parliament House. There was minimal security. Dirty tricks were possible. A scratchy photocopy of a letter purportedly from Cairns to Harris was published in the Murdoch press. In the letter, Cairns invited Harris to identify possible sources for a foreign loan and offered a finder’s fee of 2.5 per cent. Cairns vehemently denied signing the letter. He claimed he had always opposed both unconventional loan raising channels and offering any commission, let alone such an eye-watering fee. His denial seemed credible.

Nevertheless, Harris claimed the letter was genuine. It was common knowledge that Cairns was distracted, and his office was chaotic. He refused to go quietly. Whitlam forced him to resign for misleading Parliament. Cairns stoutly maintained his denials to the end of his days.

Today, the case against Cairns would look pathetic. Perhaps most suggestive is that the CIA, in reporting Cairns’s downfall, stated in its classified National Intelligence Daily that “some of the evidence had been fabricated”.

Ironically, the CIA would have probably done better if they had allowed Cairns to remain in office. They had failed to understand that their bête noire was a beast no more. Cairns was a failure at Treasury and his affair with Junie Morosi was the daily talking point at the nation’s water coolers. Under several new ministers, including Bill Hayden as treasurer and Jim McClelland running wages policy, the government’s fortunes began to improve. Whitlam gave the loans affair a thorough airing in parliament with Ministers and officials required to produce every relevant document. In August, Hayden produced a well-crafted budget that cut government spending and met with general approval. For the first time in Australia’s history, the nation was awarded a ‘Triple A’ credit rating.

Button remarked to McClelland the government was looking better. “Yes,” the minister replied, “but all our problems come out of a blue sky.”

At the end of June, while the Cairns affair was playing out, Labor Senator Bert Milliner died in his Brisbane office. If Premier Bjelke-Petersen broke convention and appointed a non-Labor replacement to the Senate, as had recently occurred in NSW, the opposition would have the numbers to block supply.

The Queensland premier may have needed no encouragement to break a convention act in this way, but it has recently come to light that a most improper intervention by the US ambassador helped ensure he did so. A telephone operator in Brisbane, Win Nash, eavesdropped on a conversation between Marshall Green and Joh Bjelke-Petersen in which Green encouraged the premier to ensure the Senate vacancy was filled by a candidate “favourable” to their cause.

Some academic experts who require contemporary documented references to verify such occurrences remain sceptical about this. Yet the detail provided by Nash’s two children, 12 and 13 at the time, and the sheer banality of the domestic milieu in which their politically aware mother related what must to her have seemed a momentous event attest to its veracity. A Labor supporter, her desire to warn Whitlam battled the potential legal consequences of doing so. Unsurprisingly, it was a battle the law won.

The revelation provides confirmation that the US administration was engaged in a conspiracy to destabilise the Australian government in 1975, with the ambition of ejecting it from office.

As former CIA officer Ralph McGehee said, in any destabilisation campaign, “the first thing that the Agency attempts to build or create is penetration into the media”. When he arrived in Australia, Green developed a beneficial relationship with Rupert Murdoch, whom he told Kissinger was “well informed and extremely influential”. Murdoch told Green in November 1974 that Whitlam’s policies were damaging the Australian economy, that an election would likely occur a year later and that he would be supporting the opposition. He praised Malcolm Fraser as best suited to become prime minister. In January 1975, the US Consul-General in Melbourne reported back to Washington that “Rupert Murdoch has issued [a] confidential instruction to editors of newspapers he controls to ‘Kill Whitlam’”.

Malcolm Fraser was clearly the key player whom the Americans needed to influence. Curran reveals a telephone call in July 1975 between Green and Fraser in which the threats to the alliance were obviously discussed. Fraser suggested to Green that the Labor government had a “desire for a ‘non-aligned position in world affairs’. In fact, he added, ‘Whitlam and others may be trying to cause the US to take the lead in abandoning ANZUS’.”

This may have been the last straw for Fraser. In any case he appears to have decided after this phone call that he was going to block supply. This was revealed in 2022 in a speech delivered by Alan Jones, Fraser’s speechwriter in 1975. Jones met Fraser after listening to Hayden’s budget speech, which was on 19 August, because he was responsible for drafting the reply. Fraser was in company with the leaders of the Country Party, with no other Liberals present. Jones told Fraser, “it was a very responsible budget speech, really difficult to answer’. And before I could finish saying anything, Peter Nixon said, ‘We’ll be rejecting supply’.”

If Jones’s memory can be relied on, Fraser had made up his mind to block supply almost two months before he announced it on 15 October. The reason for the delay would have been because Fraser lacked the requisite extraordinary and reprehensible circumstances required to justify the denial of supply.

The return of the gift that kept on giving, namely the loans affair, seems suspiciously fortuitous at this time. Rex Connor – ‘The Strangler’ – had become obsessed with raising an overseas loan. It was obvious to all and sundry, except Connor, that his chosen intermediary, Tirath Khemlani, was a charlatan and possibly an agent of some third party.

In October, Peter Game from the Melbourne Herald tracked down Khemlani and published a story contradicting Connor’s assurances that he had stopped actively seeking foreign borrowings after his commission was withdrawn. Connor sued the newspaper. A week later, his briefcase bulging with telexes Khemlani descended on Australia, seemingly intent on involving the prime minister in the affair.

The obvious question of cui bono arose. What was Khemlani motive? Dishing the dirt on a major client is not generally a career enhancing move for executives in the financial sector. Did money change hands? The journalist involved said that Khemlani “did not ask for money and nor was he paid anything”. Two opposition frontbenchers, Philip Lynch and John Howard, spent hours with Khemlani at Canberra’s downmarket Wellington Hotel. They emerged with nothing of substance.

The Khemlani affair has resulted in a mass of allegations over the years. Like George Harris, Khemlani was supposedly linked to a company called Commerce International, a front for the CIA. Christopher Boyce was said to be reading the telexes that were intercepted at Pine Gap and that further telexes were forged by Task Force 157. If so, the forgers didn’t do a very interesting job. None of the telexes produced anything of interest. Connor was accused of continuing to seek a loan after his commission had been withdrawn. He denied it. He was accused of not submitting every document for the parliamentary inquiry in July. He denied that too. The prime minister sent John Menadue to secure Connor’s resignation. On Paul Keating’s advice, Connor told him to “bugger off”.

Eventually Connor resigned. In a radio interview “he denied communicating with Khemlani. He likened the media coverage to the ‘big lie’ technique of Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels.” Listening to the interview today, he sounds ill, exhausted and resigned to his fate. Arguably, his statement also has the ring of truth about it.

The whole episode was a media circus, blown up out of all proportion to the seriousness of any misdemeanour if, indeed, there was a misdemeanour at all. It reeked of dirty tricks. Yet as Mungo MacCallum put it, Fraser had discovered the “footsteps of a giant reprehensible circumstance”. On 15 October he stated that the Coalition would block supply in the Senate.

With the exception of the Murdoch press, the media were generally critical of Fraser’s justification for denying supply. Fraser himself seemed to lack confidence in his case. As Don Whitington, a veteran political correspondent, wrote:

“Mr Fraser, fairly obviously, has no great stomach for the fight facing him. A conservative himself, all his instincts would be to follow the conventions that have existed since his grandfather sat in the first Australian Senate in 1901. … No political leader in my 35 years in Canberra has performed so ineffectually and been so embarrassing to his own supporters as Mr Fraser at his press conference in Canberra yesterday.”

Nevertheless, the Whitlam government was now entering the end game.

Read more of this series from Jon Stanford and from the Dismissal at 50 series.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.