The Prince and the Dismissal

November 7, 2025

Anthony Albanese recently told us with bated breath from Balmoral Castle that Charles “is someone who is very interested in Australia”. “Interested “would be an understatement.

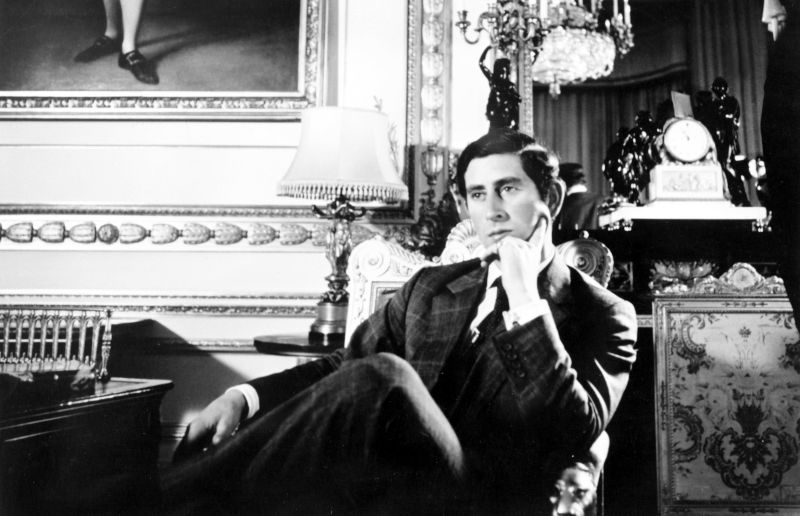

Charles was a very active participant in the dismissal of Gough Whitlam 50 years ago. Don’t make any mistake about that. Charles was up to his royal ears in it. He was not politically neutral. He sided with privilege and aristocracy.

And I am also certain that our prime minister never raised the dismissal with Charles. That would have been poor form!

Not surprisingly, I am also certain that our media did not question either our prime minister or the British King about the latter’s active role in the dismissal. The National Press Club would not have been interested either.

Prince Charles has form in intervening in Australian public affairs. And then governor-general Sir John Kerr facilitated it.

In the Dismissal Dossier 2017 edition, Professor Jenny Hocking recalls the grovelling relationship that Kerr developed with Charles. “In later private letters to Prince Charles and with the most differential and subordinate genuflection ‘I have the honour to remain, Sir, your most loyal and obedient servant’ Kerr would refer to these conversations as lasting moments of treasured privilege. ‘I have the very great privilege of remembering a number of conversations which you have been kind enough to have with me in past years’.”

Hocking reveals some disturbing features in this relationship during Charles’ visit to Australia in 1974. Both Kerr and Charles were obviously worried about their job prospects. Kerr had been blessed with a startlingly frank discussion about the prince’s endless wait to ascend to the throne. Kerr discussed with Charles the suggestion that he might one day come to Australia as governor-general.

Tina Brown, in her book _The Diana Chronicles,_ says Charles “really wanted the job (as governor-general) because he saw it as a way to get the hell out of the grip of Prince Phillip and the Queen”. Who could blame him?

Kerr was sticking his nose into an area of responsibility that belonged to the prime minister and no one else. But it gives a glimpse of Kerr’s pretensions. Whitlam knew nothing about this secret discussion.

As a consolation prize for Charles, Kerr suggested to Whitlam that it would be a good idea if the Commonwealth Government purchased a large rural holding with appropriate homestead, servants, upkeep and furnishings, to encourage the Prince of Wales to make more regular and longer trips to Australia. The poor fellow did not have enough to do to keep himself occupied. Whitlam rejected the suggestion.

What a meddler!

Hocking writes that, “In the heat of early spring 1975, in New Guinea, the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, sidled up to Prince Charles and suggested a quiet chat. Their topic? The possible dismissal of the prime minister whose guest they were at the Papua New Guinea Independence Day celebrations. Kerr’s prime concern in confiding this exceptional matter of state to the Prince was, as ever, his own job security.

“Charles seemed only too pleased to let Kerr ingratiate himself. The reason was clear: Kerr was looking for friendship and support wherever he could. Charles allowed himself to be drawn into the collaboration to bring down an Australian Government.”

(In his own papers) Kerr recounts Charles’ solicitous response to the governor-general’s concern for his own possible recall by Whitlam, should Whitlam hear that Kerr was even contemplating dismissal: “but surely Sir John, the Queen should not have to accept advice that you should be recalled at the very time should this happen when you were considering having to dismiss the government”.

After the dismissal, Charles told Kerr: “What you did last year was right and the courageous thing to do.”

Mountbatten’s biographer declared that Mountbatten, Charles favourite uncle,” much admired Kerr’s courageous and constitutionally correct action" in dismissing Whitlam.

A gaggle of royals all collaborated with Kerr in the dismissal of the Whitlam Government – the Queen, Prince Philip, who called Whitlam “a socialist arsehole”, Prince Charles and Lord Mountbatten.

The serious plotting began after Prince Charles and Kerr spoke in New Guinea in September 1975.

Tomorrow: Murdoch, the Dismissal and my job in Japan

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.