Led Zeppelin, my band that never ‘made it’, and the lost art of failure

November 30, 2025

Our culture treats success as virtue and failure as personal flaw. Older traditions – from Greek tragedy to Christian thought – saw failure as meaningful. Recovering that wisdom may be essential to living with dignity in an age of burnout.

“If you have something that you know is different in yourself, then you have to put work into it – you have to work and work and work. You also have to believe in it. But as long as you can stay really true, your aim is true, you can realise your dreams. I do believe that. Because this is what happened.”

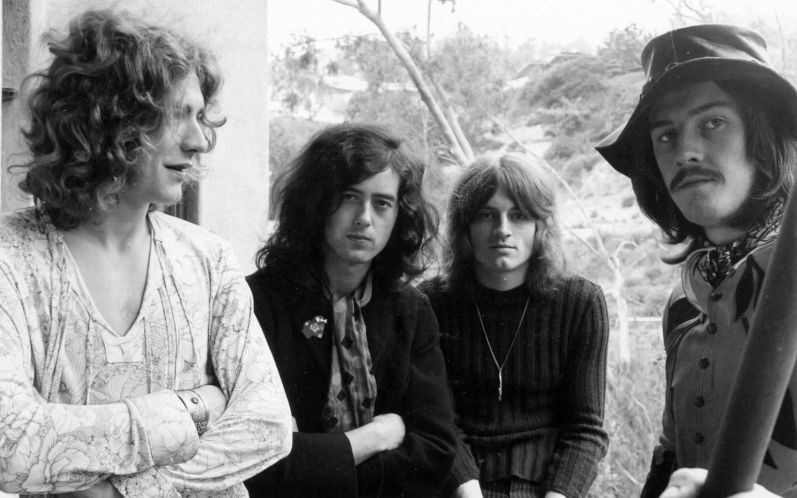

This quote from Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page in the closing scene of the new documentary _Becoming Led Zeppelin_ (2025) sounds like the perfect inspirational message: believe in yourself, work hard, and your dreams will come true.

But beneath the uplifting tone lies a troubling cultural logic that moralises success and individualises failure, as if the only meaning life can have is to “make it.”

Led Zeppelin’s success was not simply the product of talent or tenacity. As the film shows, it also depended on a booming record industry, a countercultural audience, and a manager who fiercely protected their creative freedom. Page was undeniably gifted and driven, but to universalise his path is to affirm a culture that leaves little room for the deeper truths found in failure. These truths were once woven into the fabric of an older tradition.

I learned this the hard way.

In 2008, my documentary _Sunstruck_ was released. Unlike most music documentaries, it did not tell a story of triumph. Instead, it followed 10 years in which my band, Waxing The Sun, did everything except become famous. We wrote songs, made albums that we gave away for free, played to pensioners in empty parks and alienated hospital staff at a Christmas party.

To put it lightly, we failed to achieve my youthful dream of being “bigger than The Beatles.”

Audiences didn’t just laugh. Many recognised the sadness of clinging to a dream that never arrives, and the deeper shame of living in a culture that treats failure as a moral flaw. The film’s tagline asked: “99 per cent of bands don’t make it big. Most break up early. But what happens to the ones that don’t give up?”

That question, what becomes of those who persist without reward, is one our culture rarely asks.

This was not always the case. For centuries in the West, failure was not only visible, it was meaningful. In the Christian tradition, worldly defeat is redemptive: Christ’s tragic, humiliating crucifixion was a loss that revealed a deeper truth. Saints, mystics, and reformers carried that idea forward, showing that rejecting worldly power could be a path to deeper meaning.

The ancient Greeks also knew that failure was intrinsic to human existence. In tragedies like _Oedipus Rex_ and _Antigone_, downfall comes not from laziness but from the limits of human agency. Tragedy made failure visible, even noble, and offered catharsis in facing it.

Today, that inheritance is fading. Spiritual or metaphysical understandings of failure have been replaced by a therapeutic mindset shaped by neoliberal culture. Since the 1980s, we have been taught that success is proof of individual effort and failure a sign of personal defect, turning tragedy’s collective catharsis into the private burdens of therapy, self-blame, and self-management. South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls ours “the burnout society”: a culture that exhausts people through constant productivity while erasing the collective dimension of suffering.

When I look back at my summation of our band’s failure in Sunstruck, I hear that same logic:

“For the most part we are damaged people … we all came out with some damage. But that’s to be expected. Nothing was done with any half measures.”

Here I am describing burnout as if it were just the price of passion, rather than the product of a system that measures worth only by visible achievement.

Arthur Miller saw the danger of this mindset long before the phrase “burnout society” existed. In the BBC documentary _The Century of the Self_ (2002), he rejected the therapeutic reading that Willy Loman in _Death of a Salesman_ (1949) was simply suffering from depression. That view, he argued, reflects the belief that: “Suffering is a mistake, or a sign of weakness, or a sign of illness, when in fact … the greatest truths we know have come out of people’s suffering.” For Miller, Loman was not a weak man but a tragic figure crushed by the myth of the self-made man, a victim of cultural and economic forces that neoliberalism reframes as personal pathology – someone in need of antidepressants.

It is telling that neither Loman’s story nor mine concludes with redemption. Without the older frameworks of tragedy or spiritual meaning, failure becomes a private pathology. Instead, we need to better recognise failure as part of the human condition. That means telling stories like Sunstruck alongside those of Led Zeppelin.

Jimmy Page’s understanding of Led Zeppelin’s success reveals the cultural lens through which we now view human worth. In the neoliberal imagination, success is proof of virtue and failure a mark of inadequacy. Yet the deeper heritage of the West, from the tragedies of ancient Greece to the crucifixion of Christ, tells a different story: that failure is not only inevitable but can be the very ground of transformation.

If we can reclaim that wisdom, we might free ourselves from the exhausting demand to “make it” and learn to value the quiet, redemptive dignity of those who persist without worldly reward.