Of social cohesion, belonging and the Australian flag

November 1, 2025

Until recently, “social cohesion” was a term rarely uttered by Australian politicians. Then suddenly, it was everywhere – in press conferences, speeches and ministerial statements. But what does it actually mean?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was little talk of “social cohesion” – no special envoy, no national conversation about how racism fractures our social fabric.

Fast forward to 2024. After Israeli forces began their assault on Gaza and global outrage mounted, Australians found themselves grouped into camps – “pro-Israel”, “pro-Palestinian” or, as many supporters of peace prefer, “pro-humanity”. Suddenly, “social cohesion” became the government’s new rallying cry – an initiative everyone was expected to support, though no one had really been told what it actually meant.

The Albanese Government even appointed a “Special Envoy for Social Cohesion”, Peter Khalil, to report directly to the prime minister. Yet, there was no consultation, no visible engagement, no report. Then, in May 2025, after just 10 months, the role was quietly abolished. What does that say about a government that is now so keen to push social cohesion?

And so, we’re left asking: what does “social cohesion” mean in practice? Is it pollie-speak for “don’t protest”? That we should stay home and silent, even as genocide unfolds in real time? Is it code for multicultural communities to “behave”? Or a warning dressed up in sociological jargon – that “harmony” must take precedence over morality, or even humanity?

Politicians themselves often undermine cohesion with their dog-whistling and racist rhetoric. Governments can fracture it just as easily as they invoke it – by deciding whose pain matters, whose racism counts and whose doesn’t. The appointment of a Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism, and later one to Combat Islamophobia, sent a clear message: some forms of racism deserve dedicated attention, while others are expected to rely on existing protections.

The Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975 already makes it unlawful to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate someone on the basis of race, colour, or national or ethnic origin. Yet somehow, that law was deemed insufficient for some, but entirely adequate for others – people of Indigenous, Chinese, Indian, African and other backgrounds who also face racism daily.

Does creating a hierarchy of racism foster cohesion?

For all the talk of social cohesion, what we are really grappling with is belonging – who feels they belong and who is made to feel they do not. The language of cohesion implies the fabric of Australia is fraying, yet belonging has never been evenly woven. Some are born wrapped in the flag; others are asked, again and again, to prove their place beneath it. The Australian flag, held up as a symbol of unity, too often becomes a banner of exclusion – waved to assert dominance rather than shared identity.

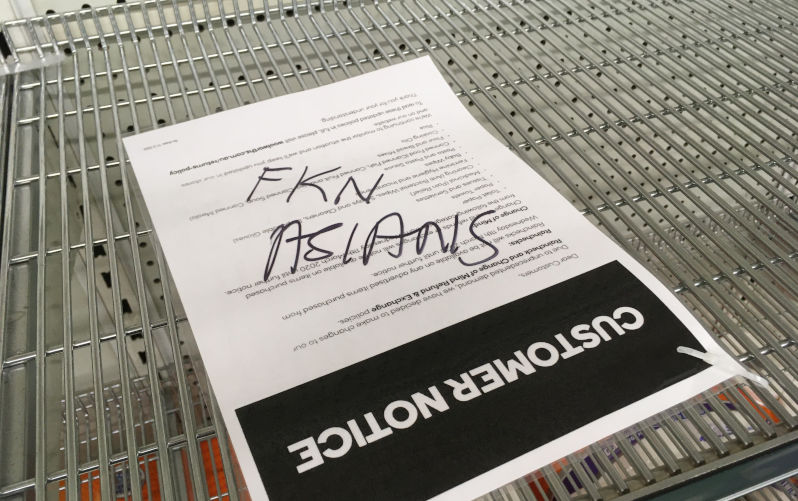

The flag flies above parliaments as a symbol of unity, yet those same parliaments have legislated exclusion. Think of the White Australia Policy. It is draped on the shoulders of Olympians, schoolchildren and protesters alike – a symbol of both pride and division. In recent times, it has been brandished at rallies where “patriotism” has come to mean hostility towards difference. Under that flag, some Australians are told to “go back where they came from”, even if their families have been here for generations.

The recent “March for Australia” showed how the flag’s meaning has turned from a symbol of unity into one of exclusion. Many marchers draped themselves in it as they protested against what they called “mass migration”. The message was unmistakable: migrants are not welcome. The flag that fluttered above those protests is the same one placed in the hands of new citizens at every citizenship ceremony across the country.

In those ceremonies, people who have met every requirement — studied the values booklet, sat the citizenship test and taken the oath of allegiance — become Australians in law and in spirit. They stand beneath that flag as equals with all other Australians – at least, that is how it is meant to be. Yet, for too many, this change of status is never fully recognised. To those who see Australia as inheritance rather than shared home, we remain forever “migrants”, our belonging provisional and our loyalty suspect.

What makes these marches even more troubling is who they stand with. – people whose ideology is built on racial superiority and hate. That alliance lays bare what their outrage over “mass migration” is really about: race and who they think Australia belongs to.

And if we’re honest, we know this isn’t directed at everyone born elsewhere. It is aimed, more often than not, at people of colour. A blonde, blue-eyed newcomer is rarely described as a migrant once they’ve settled in. The rest of us can live here for decades, raise families and contribute to our communities, yet still be spoken of as outsiders. How long must you live here before people stop calling you a migrant?

Maya Angelou once said, “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” I will never forget how Peter Dutton, as federal immigration minister, made me feel.

Under his watch came the threat to send Border Force officers into Melbourne to conduct random visa checks – as if we lived under an authoritarian regime. Even after a decade as a citizen, I felt an unmistakable chill. The intent suggested that racial profiling was probable – permissible, even. For the first time since coming to live here, I felt afraid of my own government and its institutions.

That experience stayed with me. It was one of the reasons I ran as an independent in the recent federal election, when Dutton sought to become Australia’s prime minister. Because if we don’t challenge the language and actions that make some of us feel lesser, what good is social cohesion?

The authorities backed down from their threat to conduct random visa checks – only after a public outcry, a snap rally that reminded us Australians will stand up against injustice when they see it.

This is what genuine cohesion looks like: a shared commitment to justice and the courage to stand together when belonging is denied. If the government truly cares about how we cohere as a society, it can start by eliminating racism for all Australians, not just some. The Australian Human Rights Commission has already done the hard work, producing the National Anti-Racism Framework, a comprehensive roadmap. The government has had its 63 recommendations since November last year. The question is, will it act?

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.