‘Spooky fiddling’: Preparing the ground – Part 3

November 12, 2025

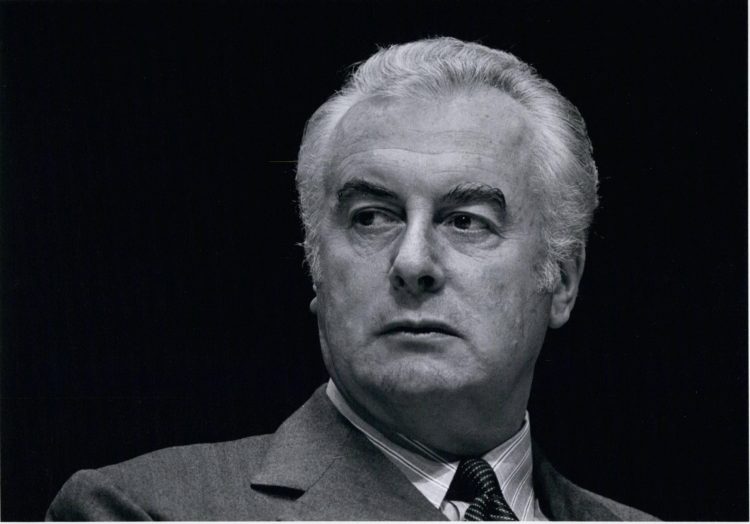

“There is profoundly increasing evidence that foreign espionage and intelligence activities are being practised in Australia on a wide scale… I believe the evidence is so grave and so alarming in its implications that it demands the fullest explanation. The deception over the CIA and the activities of foreign installations on our soil… are an onslaught on Australia’s sovereignty.” – Gough Whitlam, House of Representatives, 1977

In July 1977, Warren Christopher, deputy secretary of state under the new Democratic president, Jimmy Carter, flew into Sydney exclusively for a brief meeting at the airport with Opposition leader Gough Whitlam.

As Whitlam records in his memoirs, Christopher told him that president Carter had instructed him to say that: “The Democratic Party and the ALP were fraternal parties. He respected deeply the democratic rights of the allies of the United States. The US Administration would never again interfere in the domestic political processes of Australia. He would work with whatever government the people of Australia elected.”

Much to the frustration of his private secretary, Richard Butler, Whitlam asked no questions and made no direct response to Christopher’s statement. It has been widely observed that even long after the event, Whitlam seemed traumatised by his dismissal. But Butler drew a strong conclusion from Carter’s message: “It seemed obvious to me that the US had a role in the dismissal . . . eavesdropping, colluding with the actors and people like Kerr . . . encouraging them."

The circumstances around the dismissal were such that from the very beginning there was a suspicion of conspiracy, possibly involving intervention by the intelligence agencies in the US and Britain. Even before the dismissal took place, there was a suspicion of CIA activities in Australia. Whitlam himself raised the issue in early November, creating, as we shall see, a furore in Langley and the White House. Days before the dismissal, a detailed piece by Brian Toohey in the Australian Financial Review on the CIA’s presence in Australia clearly attracted the interest of the governor-general. It was among the news clippings Kerr sent to the Queen’s principal private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, at Buckingham Palace.

In 1983, an American academic, Professor James Nathan, writing in _Foreign Affairs_, proposed that “a plausible case is being developed that CIA officials may have also done in Australia what they managed to achieve in Iran, Guatemala and Chile: destroy an elected government – in the case of Australia, the Labor Party government from 1972 to 1975”. Nathan quoted Bill Colby, who noted in his memoirs, Honorable Men, that among the problems he had to deal with as CIA director included “crises like . . . coups in Cyprus and Portugal a nuclear explosion in India and a Left-wing and possible antagonistic government in Australia”. The question left hanging is what action his “honourable men” took to address the “crisis” in Australia.

In examining whether covert action did take place in Australia in 1975, two important points should be made. First of all, CIA interference in sovereign states was by no means unusual at that time; it was so common as to be almost de rigeur. This was the peak of what author Joseph Trento calls the “Dark Period” in the CIA’s history, Taylor Branch wrote in The New York Times in 1976, “the Congressional inquiries in the previous two years showed that the CIA, in some 900 foreign interventions over the past two decades, has run secret wars around the globe and has clandestinely dominated foreign governments so thoroughly as to make them virtual client states”.

Former CIA officer Ralph McGehee said in 1986 “I don’t think there is a government in Latin America that has been neither overthrown nor supported by the CIA. And probably I would say much the same for governments in the Middle East and … Africa.”

Even in fellow Five Eyes countries, the CIA flouted the protocol of non-intervention in their partner nations’ affairs. Richelson and Ball show how the agency made large donations to provincial political parties in Canada. They cite a dispute in the late 1960s between Richard Stallings, in charge of the CIA facility at Pine Gap, and the CIA head of station in Canberra, who was running an operation (probably in collaboration with ASIO) to undermine the anti-war movement and the ALP. Anticipating a future Labor government, Stallings wanted the CIA to do nothing to offend the party because of possible implications for Labor’s future attitude to Pine Gap. Also, covert action is just that: covert. CIA (and MI6) officers and their agents are extremely well trained and rarely get caught. They are unlikely to leave any trace of their work. Even 50 years after the dismissal, there are likely to be no documents in the public domain that could still cause difficulties in diplomatic relationships. As Taylor Branch said of CIA doctrine, “smoking guns are considered thoroughly unprofessional in clandestine operations”.

This is illustrated by the scanty orders with which CIA director Richard Helms emerged from a meeting with Nixon and Kissinger that lit the fuse on the Chile operation. In a near illegible note that Helms should probably have destroyed, his instructions are clear: “1 in 10 chance, perhaps, but save Chile! Not concerned [about] risks involved. No involvement of embassy. $10,000 available, more if necessary. Full time job – best men we have. Make the economy scream! 48 hours for plan of action.” This “remains the only known record of a US president ordering the covert overthrow of a democratically elected leader abroad”.

Secondly, and as illustrated by Helms’ note, if covert action did take place in Australia in 1974-75, it is wrong to ascribe responsibility to the agencies themselves. The CIA was not an autonomous organisation; it operated under the authority of the White House. From August 1974, as we have seen, Henry Kissinger was in effective control and dealing with the Australian problems from his position of national security adviser. Any covert operation to destabilise the Australian Government would have been authorised at the very highest levels of the administration. Intervention in Australia, which is different from Chile and other countries where the CIA plied its trade, would be particularly sensitive. Australia was a mature democracy that occupied an entire continent and had the 13th largest economy in the world. It was a major US ally that had fought alongside America in every conflict in the 20th century. It was a member of what is now the Five Eyes exclusive intelligence sharing group. To mount a covert operation against the Australian Government was a monumental decision for any US president to make. It would have been essential to avoid leaving behind even a wisp of smoke, let alone a smoking gun.

In his book Secret, published in 2019, Toohey has assembled a mass of evidence to sustain the contention that the CIA and Kissinger’s much smaller covert action force, Task Force 157, was active in Australia in 1975. Nathan’s earlier article in Foreign Affairs contains detailed information and provides some names. Former CIA officers, their contractors and well-informed insiders have provided ample support for this claim. Victor Marchetti, a former senior CIA officer who was involved in establishing Pine Gap as deputy to Stallings, said in 1980 “the CIA’s aim in Australia was to get rid of a government they did not like and that was not co-operative… it’s a Chile, but in a much more sophisticated and subtle form”. Earlier, he said Whitlam’s threat not to renew the lease on Pine Gap “caused apoplexy in the White House. Consequences were inevitable … a kind of Chile was set in motion".

Another former CIA officer, Robert McGehee, identified two senior officers involved in the Australian intervention. One was Ted Shackley, Kissinger’s “go to” CIA operative and a key player in the earlier Chile operation. The other was Ed Wilson, a friend of Shackley and now head of Task Force 157. McGehee asserted there was “all sorts of evidence that Task Force 157 was also orchestrating the efforts to overthrow the Whitlam government”.

Christopher Boyce, a cipher clerk in California who decoded material from Pine Gap, was arrested in 1977 for sharing the secrets with Moscow. He justified his treachery by expressing his disgust with CIA operations in Chile and Australia, where they had destabilised the Whitlam Government and infiltrated trade unions. According to Boyce, the CIA took a close interest in the blocking of the 1975 budget. He claimed the CIA officer in charge of his unit referred to the governor-general as “our man Kerr”. It is difficult to see why Boyce would have fabricated any of this; indeed, revealing these secrets could only have contributed to the length of his 40-year sentence.

Over the last half-century, US authorities have been vigilant in suppressing information on covert intervention in Australia. At Boyce’s trial, the CIA formally instructed the judge not to allow any evidence on operations in Australia, presumably on national security grounds. Toohey reveals that the CIA took court action against Marchetti and his co-author to remove the most sensitive information before they would allow publication of their book, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence. With one minor exception, this included every reference to operations in Australia. Much more recently, the Ford library refused James Curran’s request for the release of the remaining redacted sections of NSSM 204 and the associated critically important material on the approach the US would follow to resolve its substantial problems with the Whitlam Government in 1974-75. When Curran sought a reason for the decision, the librarian stated a concern, even 50 years after the event, for the possible impact of the release on US-Australia relations.

Having, arguably at least, substantiated the proposition the CIA were active in Australia in 1974-75, we now move to the question of their modus operandi. In his book CIA Diary, Philip Agee, a former CIA officer who served in Latin America, reveals many details of the CIA playbook. In discussing a CIA destabilisation campaign in Jamaica, Agee proposes that “no major political action of that nature would have been undertaken without the approval, and probably the participation, of the British. After all, special rules apply for CIA operations in Commonwealth countries".

In 1988, British MP Tam Dalyell raised the issue of British involvement in Whitlam’s dismissal in the House of Commons. He referred to a TV interview with CIA insider Joseph Trento, author of The Secret History of the CIA. Trento is quoted as saying:

“I have it on authority at the highest levels of the US intelligence community that there was genuine concern over the loss of those bases. I don’t think you could say the CIA forced Kerr to sack Whitlam, but I think that decisions were made that led to his sacking based on what the CIA was telling the English. They made a recommendation for the demise.”

Martin Pearce, biographer of the chief of MI6, Maurice Oldfield, suggests that his subject was involved in the events of 1975 in Australia. Pearce’s version differs from Trento’s, however, in that the CIA didn’t alert the British to the problems in Australia; rather it was Oldfield who was first on the phone to Bill Colby. Justice Robert Hope, head of Whitlam’s Royal Commission on the security services, had, quite improperly, told Oldfield that Whitlam was considering severing all connections with the CIA. Oldfield immediately recognised this could have existential implications for Pine Gap. He called Colby and they agreed that “something must be done”.

The symbiotic trio of ground stations, Pine Gap, Menwith Hill and Buckley, was equally important to the UK as to the US because of the critical role it played in providing warning of a Soviet attack. Nevertheless, the retention of Pine Gap would not have been a vital issue for the UK because the Americans would surely move the facility somewhere else at their own expense. For Britain’s Labour government to authorise covert action against the Whitlam Government would have been very unlikely and Oldfield would not launch an operation against Australia without his government’s approval. What he may have done, however, is turn a blind eye to US covert activity in Australia and ask to be kept informed.

Another even more problematic issue is the possible participation of Australia’s own security services in this undertaking. It is reasonable to assume that even if they were only halfway proficient in their calling, Australia’s senior intelligence officers would be able to detect incursions by supposedly friendly foreign services opposed to the Australian Government.

In this regard, Victor Marchetti made a disturbing observation:

“The CIA does not take these actions on itself. It’s done in co-operation with the local intelligence services and they, of course, provide assistance and protection. Look, you find out where the loyalties of your intelligence services lie. Do they lie with your country as a whole, for better or worse, or with the Establishment in your country? And in most instances, the answer you find is ‘with the Establishment’.”

The question around the possible involvement of ASIO and ASIS in the dismissal is complicated by Australia’s membership of the UKUSA Agreement, now Five Eyes. By the 1960s, Australia’s agencies had become closely intertwined with their opposite numbers in the US and the UK. The Australian Signals Directorate records that “the existence of the [UKUSA] Agreement was a tightly held secret for two decades; it was not disclosed to an Australian prime minister until Gough Whitlam insisted on seeing it in 1973”.

According to Richelson and Ball, Canada, Australia and New Zealand contributed between them only 2% of Five Eyes resources at that time. It seems likely, therefore, that those “junior partners” would operate in a subordinate role to the US. Intelligence was the currency of their trade. Their desire to have ongoing access to the valuable intelligence provided suggests they would be responsive to requests from their bigger brothers whose operations would be overwhelmingly designed to support US foreign policy interests. One former ASIS officer, who had operated in partnership with the CIA in Asia, advised the author that when the agency told them to jump, the only response was to ask: “how high?”

If the CIA intended to mount an operation against a left of centre government in Australia and needed some in-country assistance and support, it obviously would approach its partner agency at an officer level. It would only do that if, to use Marchetti’s framework, it could be confident the Australian agency’s loyalties lay more with the ‘Establishment’ than the government. Since ASIO was the CIA’s main point of contact in Australia, what assumption could the agency make about ASIO’s loyalty in late 1974 and 1975?

Labor came to power in 1972 justifiably suspicious of ASIO. They believed that Australia’s counterintelligence agency had been used by conservative governments to spy on left-wingers and systematically to undermine the ALP. Not long after coming to office, Whitlam established a Royal Commission into the security services chaired by Justice Robert Hope. In a report not completed until 1977, the Commission found that ASIO “had become badly politicised”. Worse still, “ASIO believed it was entitled to withhold important information from elected governments”.

Under Charles Spry, ASIO developed a very close relationship with the CIA, particularly with James Jesus Angleton, the agency’s formidable director of Counterintelligence. Access to US intelligence was ASIO’s currency and the battle against communist subversion was its mission. If there had been any goodwill for the Whitlam government within ASIO, it was blown away by two of its early actions. First, Whitlam’s letter on the Christmas bombing led to ASIO’s access to intelligence being significantly reduced. Word would probably have reached them that Ted Shackley had told his team that “the Australians might as well be regarded as North Vietnamese collaborators”. That would have caused bitter resentment, but not against Shackley. Secondly, attorney-general Lionel Murphy’s March 1973 “raid” on ASIO’s headquarters in a vain search for incriminating files brought about a complete breakdown in trust.

The ASIO raid also triggered what Angleton called a crisis within the CIA. Angleton wondered how they could “maintain relationships with the Australian intelligence services. Everything worried us", Angleton said. “You don’t see the jewels of counterintelligence being placed in jeopardy by a party that has extensive historical contacts in Eastern Europe.” In consequence, before he had been in office for even six months, the CIA made its first attempt to get rid of Whitlam. Armed with information from within ASIO, Angleton instructed the CIA station chief in Canberra, John Walker, to ask ASIO head Peter Barbour to state publicly that Whitlam had lied to Parliament about the raid. The objective was to force the prime minister to resign.

Barbour simply refused. He had taken over from Spry in 1970 and was intent on reforming ASIO so it could work effectively with both sides of politics. He had sought permission to brief Whitlam before the election, but Bill McMahon would not agree. Barbour was consistently loyal to Whitlam, but he never seemed to gain the prime minister’s trust. His defiance of the CIA now made him a target for the pro-Angleton faction within ASIO, a group known as the “Old and the Bold” led by Colin Brown who ran ASIO’s Canberra office.

There seems little doubt that if the CIA asked for limited assistance from ASIO at the officer level in destabilising the Whitlam Government, they would attract support. While Barbour would stand in the way, Brown was compiling a dossier on his chief that would eventually lead to his downfall,

When he was summoned to brief the new prime minister in February 1973, ASIS director-general, Bill Robertson, took with him a memorandum for the prime minister to sign. It instructed ASIS to close its station in Santiago established to assist the CIA in their operations against the democratically elected Allende Government of Chile. The Gorton Government had agreed to a request from the CIA against Robertson’s advice. Whitlam took the memorandum away with him, but wary of upsetting the Americans, it was a few weeks before he signed it. The station closed in July 1973, two months before the coup that resulted in the death of Allende.

ASIS worked very closely with Britain’s MI6 to the extent at this time of being a virtual branch of the British service. The two services shared offices in Asia and sometimes represented each other in stations in the region. They shared a communications system. ASIS officers referred to MI6 headquarters in London as “Head Office” and undertook the intensive MI6 training program in the UK. A former ASIS officer told the author that on arrival in London for training he was greeted by Oldfield who took him for dinner at his club. Oldfield referred to ASIS officers as “my Australians”.

But Oldfield was a Cold War warrior and the relationship between MI6 and the CIA was by far the most important one within Five Eyes. Unlike Angleton, Oldfield was not politically partisan. He enjoyed a good relationship in 1974-75 with his Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, and foreign minister, Jim Callaghan. Oldfield paid regard to due process, and it is most unlikely he would have encouraged Robertson to work against his own government. There is no indication that Robertson was disloyal to Whitlam. But, as we shall see, when Whitlam sacked him in October 1975, all bets were off. The prime minister had already made one enemy in the form of ASIS deputy director Dickie Austin, who resigned after the ASIO raid in early 1973. Now he had another.

Both ASIO and ASIS would play a role in the dismissal.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.