The Second Dismissal

November 11, 2025

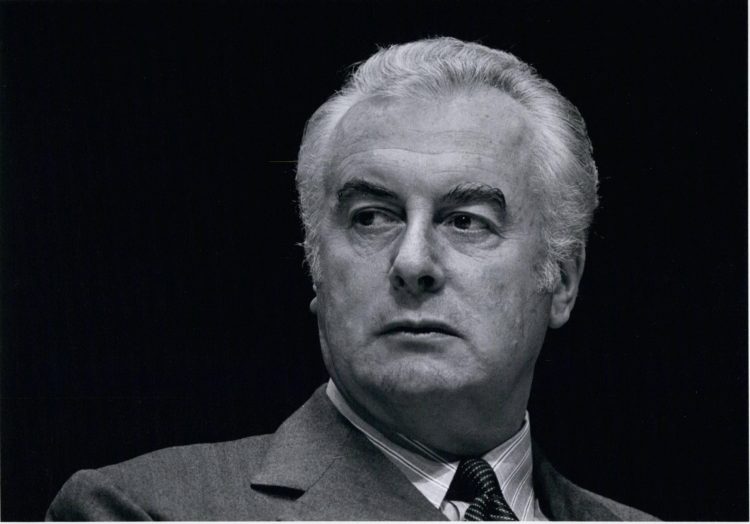

In an extract from The Double Dismissal, Emeritus Professor Jenny Hocking, distinguished fellow of the Whitlam Institute within Western Sydney University, and Dr Matt Harvey, senior lecturer at Victoria University of Technology, describe the chaos that led to two dismissals on 11 November.

Whitlam left Government House unaware that the leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Fraser, was waiting in an anteroom at the other end of the corridor, emerging immediately after his departure to be sworn in as prime minister. Whitlam only found out from journalists the following day that by the time he left Yarralumla, Fraser was already prime minister. Nor did Whitlam know that Fraser and Kerr had agreed earlier that morning on the four conditions by which Kerr would dismiss Whitlam and appoint Fraser as prime minister. Whitlam’s actions following the Dismissal took place in that fog of constructed secrecy, confusion, and deception.

He went straight to the Lodge to meet his core advisers including Freudenberg, Enderby, Scholes and Menadue, many of whom thought Whitlam was joking when he looked up briefly from his steak to tell them they had been sacked. None of them knew then that Fraser was at Yarralumla when Whitlam arrived, and that he had already been appointed prime minister by Kerr: “Contingency plans for a complete departure from accepted parliamentary practice and the accepted role of Australian governor-generals had not been prepared,” Scholes drily recalled. Their focus, such as it was given the varying degrees of shock, was on getting the supply bills through the Senate and then re-forming government through a motion of confidence in the House of Representatives in Whitlam and a government led by him.

Whitlam drafted a motion of confidence to move in the House of Representatives calling for the governor-general to again commission the Whitlam Government. It should be noted that in this frantic half-hour which focused on securing supply in the Senate and confidence in the House, no one thought to advise the Labor leaders in the Senate of the Dismissal. Had they known, they might have withdrawn the motion or otherwise frustrated the passage of the bills.

The House of Representatives and the Senate both resumed sitting at 2pm, with many Labor members still unaware that the government had been dismissed and anticipating the announcement of a half-Senate election. The atmosphere was electric as news began to filter through that the government had been dismissed. The public gallery quickly filled with shocked onlookers, distressed and in disbelief, some hanging perilously across the gallery balustrade to remonstrate. Their noise erupted and ebbed with every new announcement, and Hansard reporters struggled to keep pace. When Fraser rose at 2.39pm and announced that he had already been commissioned as prime minister by the governor-general, the House exploded.

The Senate, meanwhile, was again reconsidering the supply bills, with most of the Senators on all sides unaware that the government had been dismissed. However, the Senate officers, the clerk of the Senate, James Odgers and his deputy, Harry Evans, both knew that the Whitlam Government had been dismissed and that Fraser was now in office. Evans recounts that Odgers had told him during the luncheon adjournment that the government had been dismissed before conferring in Withers’ office. This had particular severe implications for the passage of the supply bills which can only be brought forward by the government.

Two claimants to government now fought for the confidence of the House of Representatives – the elected majority led by Whitlam and the appointed minority government led by Fraser. At 3pm, Whitlam moved a simple “want of confidence” motion in “the prime minister” Fraser, which Fraser lost by 10 votes. That same motion affirmed the confidence of the House in Whitlam and, with supply now passed, called on the Speaker to advise the governor-general to call on the member for Werriwa, Gough Whitlam, “to form a government”. The House then adjourned at 3.15pm to allow the speaker, Gordon Scholes, to inform the governor-general of its motion on the formation of government. It was set to reconvene at 5.30pm. Since supply had been passed by the Senate one hour earlier, Whitlam expected to be back in office as prime minister later that afternoon.

Scholes recounts that this was the process decided at the meeting at the Lodge immediately after the Dismissal: “all present were still prepared to believe that the governor-general would act on a resolution of the House of Representatives in accordance with accepted precedence”. However, in an extraordinary series of events in which conventions were torn up like confetti, Fraser refused to resign as prime minister despite the motion of no-confidence against him, and Kerr refused either to acknowledge the motion of the House or to receive the speaker who would deliver it to him. When Scholes’ office rang Government House immediately after the passage of the motion of no-confidence in Fraser, he was told that the governor-general would not be available until 4.30pm – more than an hour later.

The critical role played by Justice Anthony Mason re-emerges at this point on the afternoon of 11 November 1975. While the House was adjourned, Kerr rang Mason, concerned that Fraser had lost a motion of no-confidence and that the House had called on the governor-general to re-commission a Whitlam Government. In this critical telephone conversation, only revealed four decades later, Mason told Kerr that the House of Representatives’ motion of no-confidence in Fraser, the defining motion on the formation of government in the Westminster system, was “irrelevant” and that the commissioning of Fraser as prime minister should stand. Kerr then ignored the “irrelevant” no-confidence motion and refused to see the speaker until 4.30pm.

Scholes was kept waiting at the gates of Yarralumla for a further 10 minutes before being permitted to enter. As he finally drove into Government House, the official secretary, David Smith, was driving out, on his way to Parliament House to read the proclamation which had just been signed by Fraser and Kerr dissolving the Parliament and calling the double dissolution election for the Fraser Government, based on 21 Whitlam Government bills that the Fraser-led Coalition had twice rejected.

This was Kerr’s Second Dismissal, the dismissal of the Parliament itself. It was also a second Dismissal of Whitlam, who was entitled to resume the office of prime minister having the confidence of the House of Representatives and with supply having already been granted. Instead, Fraser remained in office as prime minister and Kerr dissolved the Parliament with a live motion of no-confidence by the House of Representatives before it, and with supply no longer blocked. Professor David Corbett described this as “the most provocative aspect of his [Kerr’s] conduct; he granted a dissolution to a caretaker prime minister who lacked a majority and had been defeated in the House, instead of calling back into office the man who had just had the House’s confidence in him reaffirmed”.

Speaker Gordon Scholes, who retained his position despite Kerr’s dismissal of the government of which he had been a member, wrote to the Queen the following day in the strongest terms. The governor-general’s refusal to see the speaker and his failure to withdraw Fraser’s commission following the motion of no-confidence, Scholes wrote, “were acts contrary to the proper exercise of the Royal Prerogative and constituted an act of contempt for the House of Representatives … to maintain in office a prime minister imposed on the nation by Royal prerogative rather than through Parliamentary endorsement constitutes a danger to our Parliamentary system”.

Scholes urged the Queen to call on the governor-general as her representative to recognise the wishes of the House of Representatives and recommission a government led by Whitlam as the leader with the confidence of the House. Charteris’ terse reply established what became a central pillar of the history of the Dismissal, which archival revelations decades later have since exposed as fiction: “The Queen has no part in the decisions which the governor-general must take in accordance with the Constitution.”

Harold Wilson’s British Labour Government was quick to distance itself from Kerr’s actions: “Ministers were not involved in any way. It has nothing to do with us. It is a question for the Queen and her advisers,” government spokesmen said. The Queen and her advisers on their part insisted that they knew nothing, that they played “no part” in Kerr’s decision, and indeed had been “kept in the dark” by him. Sir William Heseltine, the Queen’s deputy private secretary, claimed the Palace had “no clue” of what Kerr was thinking, stating that “the governor-general gave no clue to any of us at the Palace what was in his mind”.

The British High Commissioner to Australia, Sir Morrice James, recognised in Kerr’s unprecedented action the powerful reanimation of the reserve powers of the Crown: “Not for many years can there have been so bold and controversial an exercise of the powers of the Crown in a constitutional monarchy of the Westminster pattern. And not for many years to come will there be an end to the political and constitutional reverberations of Sir John Kerr’s action.”

The doors of the House of Representatives and the Senate were taped shut as the proclamation dissolving both Houses of Parliament was read on the steps of Parliament House by Smith, just as the speaker was ushered into the governor-general’s study with the motion of no-confidence. One hour earlier, Smith had called the attorney-general’s department and told them to prepare the proclamation for a double dissolution and to reinstate the words that Whitlam had removed from the proclamation the previous year, “God save the Queen!”. It is this that gives full meaning to the words and the impotent fury behind them of Whitlam’s most famous speech, on the steps of Parliament House on the last day of his prime ministership, 11th November 1975: “Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’ because nothing will save the Governor-General.”

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.