To fix the economy, fix housing

November 9, 2025

Australia’s economy is in a post-pandemic slump. To dig us out, state and federal governments must tackle the chronic shortage of housing in our biggest cities.

Australia’s cities are our economic engines. The density of cities — clustering workers and firms together — lifts productivity.

And larger cities mean deeper labour markets that can attract more talented workers and facilitate better matching between them and employers.

But the price of housing in our major cities has pushed many workers away.

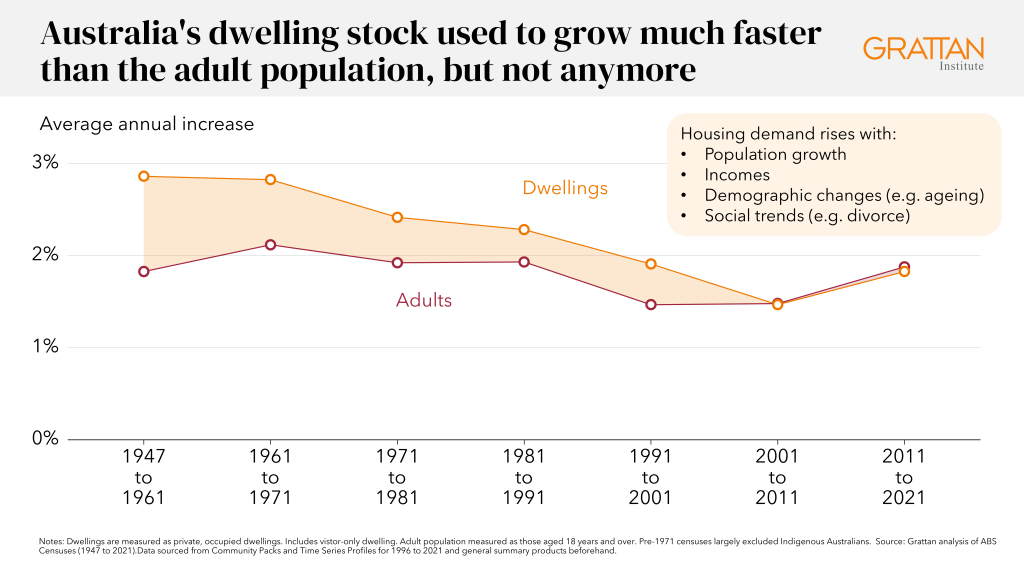

In the second half of last century, the growth in Australia’s stock of homes consistently outpaced the growth in Australia’s adult population. It meant the nation could absorb the rise in demand for housing from our booming and increasingly wealthy population, and house prices barely moved.

But since the turn of the century, growth in the housing stock has lagged that of the adult population.

Over the past 20 years, people younger than 30 have been pushed further from our city centres. From 2001 to 2024 — a period during which the population of Sydney grew by 1.5 million — the under-30 population declined in 16 inner-Sydney areas.

It’s no coincidence that our capital cities are less dense — they are home to many fewer people per square kilometre — than most other wealthy cities globally home to more than one million people.

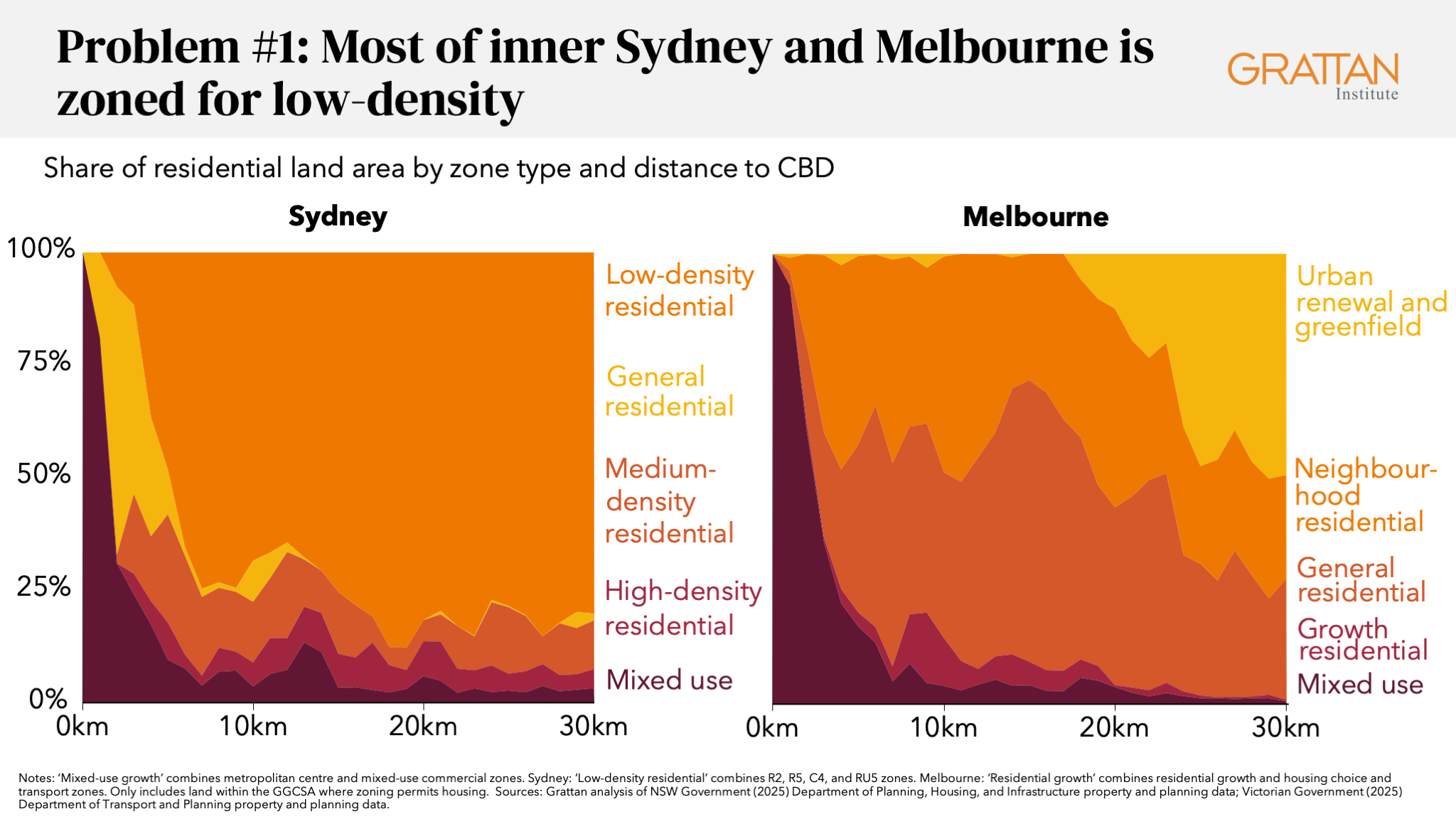

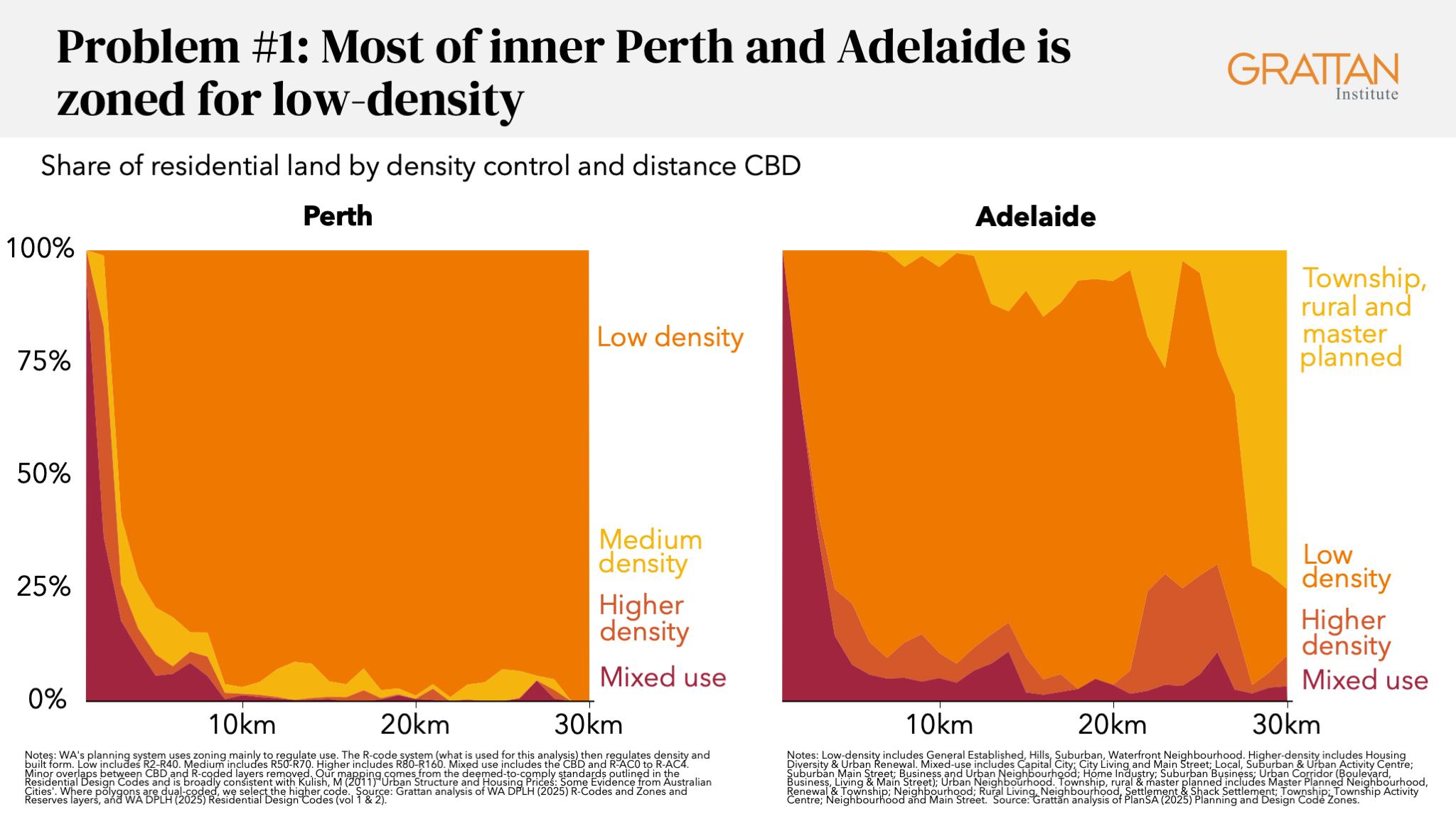

The main reason is that state and territory planning systems have made it hard to build more homes in the inner and middle suburbs of our capital cities – where Australians most want to live.

About 80% of residential land within 30km of the centre of Sydney, and 87% in Melbourne, is restricted to housing of three storeys or fewer.

And three quarters or more of residential land in Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide is zoned for two storeys or fewer.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Three key reforms are needed:

First, all state and territory governments should permit townhouse and apartment developments of up to three storeys on all residential-zoned land in capital cities, as Victoria has now largely done. These developments should not require a planning permit, just like many knock-down rebuild homes in most states already.

Subdividing large family homes for townhouses is an easy way to boost density and allow more housing on scarce inner-city land without the need for lot amalgamations. Around half of all residential-zoned blocks in Sydney and Melbourne are larger than 600 square metres, as are nearly two-thirds in Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide.

The Grattan Institute calculates that this change could unlock capacity for more than a million extra homes in Sydney alone that could be profitably built today.

Second, all state and territory governments should allow housing developments of at least six storeys around key transit hubs, as NSW and Victoria have begun to do.

Many of the world’s most iconic and liveable cities — think of Paris, Vienna and Copenhagen — allow six or more storeys broadly across much of their inner areas.

And third, taller apartment buildings should be permitted in high-demand locations, including in and around capital city CBDs.

These changes could lift housing construction by an average of up to 67,000 homes a year. That’s enough to cut house prices and rents by 12% within a decade, and more than 20% over two decades. And they could boost Australians’ incomes by up to $25 billion a year (in today’s dollars), or 1% of GDP, in the long term.

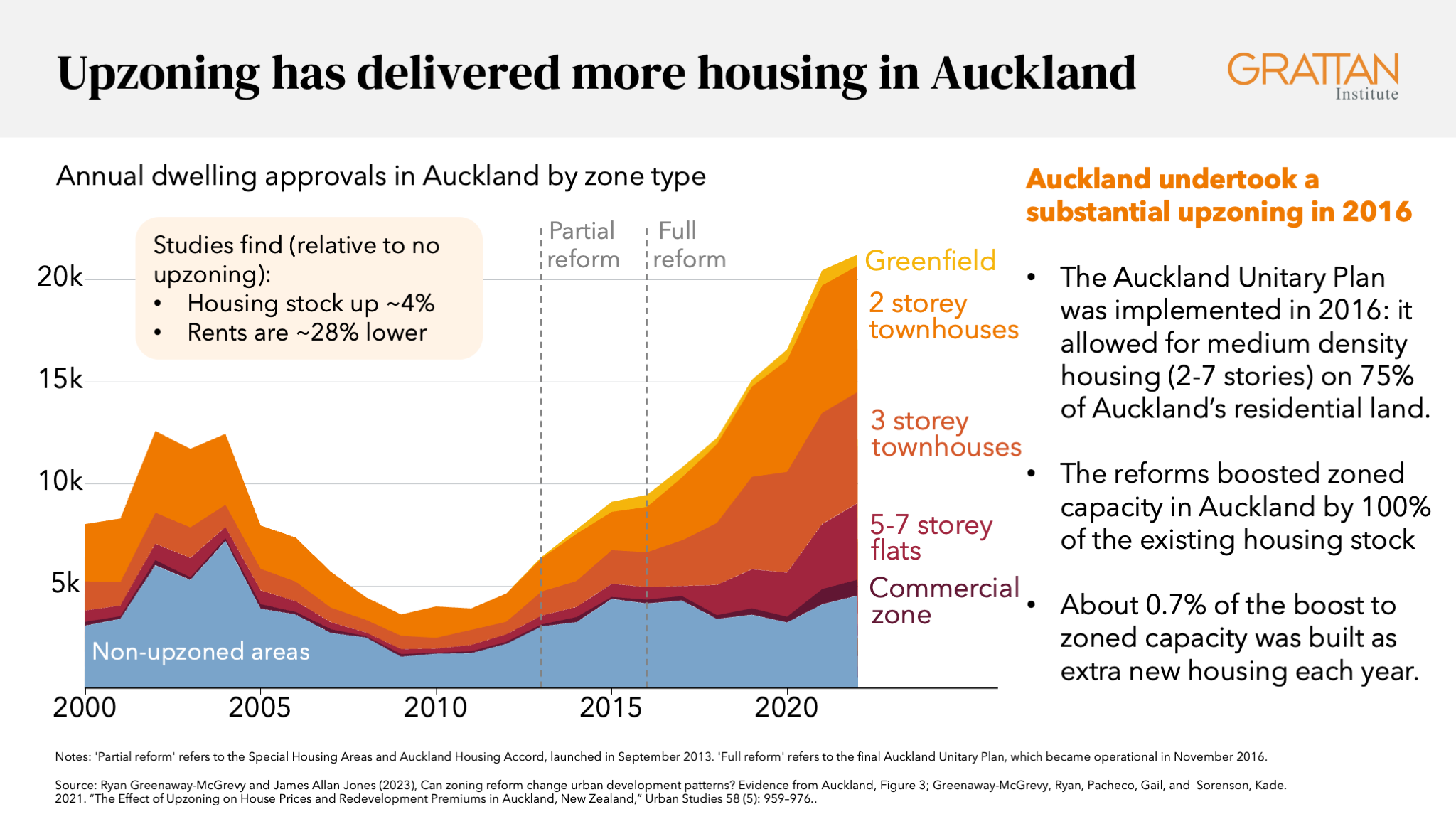

This isn’t merely theory. Auckland, which upzoned 75% of its land area in 2016, subsequently had a building boom that added an extra 4% to the city’s housing stock in just six years and reduced rents by 28%. Productivity in Auckland’s construction sector rose by 8% after the reforms.

The federal government should reward state and territory governments that adopt these reforms, by extending National Competition Policy payments to residential land use.

After all, the federal government would collect most of the extra tax revenue from the larger economy that would result.

There’s plenty of precedent for the federal government helping to pay for specific, verifiable economic reforms. Under the National Competition Policy, the Commonwealth paid the states almost $6 billion over 10 years in exchange for much-needed regulatory and competition reform. The Productivity Commission later concluded this reform boosted Australians’ incomes by 2.5%.

The federal government should also ask the Productivity Commission to regularly assess the capacity of state planning systems to meet expected housing demand and to recommend further reforms to get more housing built.

For too long, our planning systems have prevented more housing and dragged on Australia’s productivity. It’s a choice Australians can no longer afford.

Brendan Coates, Joey Moloney and Matthew Bowes are housing experts and the authors of the new Grattan Institute report, More homes, better cities: letting more people live where they want.

This article has been updated since publication. The chart ‘Australia’s dwelling stock used to grow much faster than the adult population, but not anymore’ has a corrected datapoint for the 2001-2021 period, and the surrounding text has been accordingly updated.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.