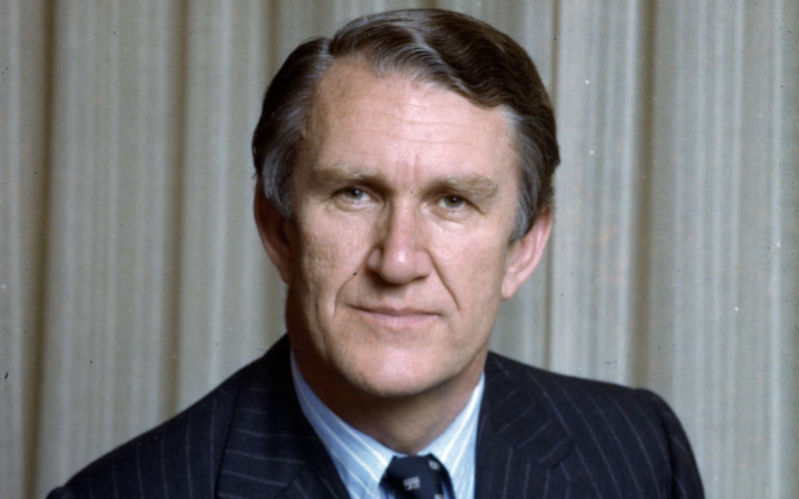

Working with PM Fraser - a country divided - Part 3

November 21, 2025

John Menadue stayed on as the most senior public servant in the land, after the trauma of the Dismissal. In this 5-part series he details what life was like working with PM Fraser. Given his closeness to Whitlam, some of his conclusions are surprising.

Malcolm Fraser never really got away from the fact that in coming to power he divided the country. That division was mirrored in his own person. In his awkwardness, he tended to push people apart.

If the Whitlam Government was over-prepared for government, the Fraser Government was under-prepared. In the three years in opposition, it did little rethink on policy. It was a matter of reclaiming its rightful position in government and performing competently.

At a discussion at the Lodge early in 1976, with his senior political colleagues and his own staff, Fraser commented that despite the brilliance and the glamour of Whitlam in 1972 against an ‘old dope like McMahon’, the Labor Party had won by only nine seats. In his view, if the Labor Party was anything like a natural party of government in Australia it would have won handsomely in those circumstances.

The lack of preparation for government and any clear direction had been highlighted in his 1975 policy speech to “give Australian industry the protection it needs,” but also claiming that a Liberal government would “make Australia competitive again.” The political rhetoric was there, but it lacked a core philosophy. Contrasting himself with the Whitlam Government, Fraser was committed above all else to managing his ministers, the public service and the economy and removing from government all waste and extravagance: “Life was not meant to be easy.”

To highlight the end of extravagance, Fraser instructed that expenditure on the reception for the new Parliament be cut. Instead of champagne we had orange juice. Fraser also tried to lower the political temperature after the frenetic days of the Whitlam Government. He told us in the department that he wanted to take politics off the front page of the newspapers.

We are all wise after the event, but the Fraser Government missed the opportunity, with a strong Prime Minister and with a record majority, to initiate reforms, particularly in industry structure. Business was protected and inward-looking. Australia had to become part of the global economy and develop its economic relations with Asia on a competitive basis. Nothing much changed, though. Hard-nosed policy development in opposition, free of the burden of government, should have better equipped the Liberals. There was no coherent framework in government.

Fraser toyed with monetarism, the Treasury fad at the time; inflation could be broken by controlling the money supply. It didn’t work. In the Fraser years, demand was not controlled through the budget and large wage increases resulted in high inflation and rising unemployment.

In fairness, however, it should be said there are convenient lapses of memory by the critics. At the time no ministers, policy advisers in the Liberal Party or business or media commentators were seriously espousing any credible alternatives. The dumping on Fraser, for failed economic policies, came well after the event.

The manner of the Fraser Government seizing power sapped its confidence and resolution from day one. I thought a nagging doubt was always there. It was tentative on tough issues. Government spending was a clear example. Ten years later, Fraser acknowledged to his biographer, Philip Ayres, that “he should have undertaken more radical surgery on the public sector in his first year.” He believed that Treasury gave him bad early advice on spending cuts. Most important of all, he was nervous about creating further social division and hardship with large expenditure cuts.

He went to great pains to try to build a consensus with the ACTU and Bob Hawke. Tony Street, the Minister for Employment and Industrial Relations, was the most reasonable person in the Cabinet and close to Fraser. They went to school together. As a result, in the early months of the Government there were compromises on Medibank, the abolition of the Prices Justification Tribunal and secret ballots in trade unions.

Fraser was interventionist across all ministerial portfolios, but Treasury resisted. It paid the price. We briefed Fraser on the regular quarterly Treasury forecasts and monthly Reserve Bank reports. He instructed Treasurer Phil Lynch that Treasury should send copies directly to him. It delayed. I wrote to Fred Wheeler confirming the Prime Minister’s requirements. Reluctantly Treasury complied but invariably the reports arrived at the last moment and too late for proper consideration. Fraser was angry with this continued defiance. The outcome was that in November, just after I had left the department, Fraser split Treasury into two: Treasury and Finance. It was for one purpose: to reduce Treasury influence. Treasury was always slow to learn that its first duty was to serve the Government.

On economic affairs Fraser was not a Thatcherite. He didn’t have any truck with ‘rational economics’ or the ‘radical right’. As a Western District grazier, he saw the world differently. People who had privilege and opportunity had responsibilities, particularly towards the underprivileged. There was a sense of noblesse oblige, and of an important role for the public sector to play.

Whitlam had mistakenly left his ministers to run their own affairs. Fraser was determined not to make the same mistake. He did it by his own strong personality and the much stronger position that Liberal leaders traditionally hold in Liberal Cabinets. He curbed ministers and restricted the number of their private staff much more than ever before. Most ministers were refused press secretaries and leakages were investigated by the Federal Police. Ministerial decisions were brought under his control. It infuriated his colleagues, but they scarcely said ‘boo’. Former ministers who now say they stood up to him must have attended different meetings to the ones I attended.

Matters came to Cabinet that really should have been left to ministers or perhaps attended to in private consultation with the Prime Minister. He was concerned about reinforcing his own authority, in a party and government that had a record majority. He was never under threat but always seemed wary.

The Whitlam Cabinet had been active and interventionist, but in this Fraser put Whitlam in the shade, as the public record shows. In the first year of the Whitlam Government, 1973, there were 1700 Cabinet submissions. In the first year of the Fraser Government there were 1900 and, at the peak in 1978, they had risen to 2700. There was an explosion in Cabinet business, whereas by all expectations the Fraser Government was going to be less interventionist and make fewer decisions. It was frenetic. Cabinet meetings were called at very short notice. Ministers did not get sufficient notice. The workload that we had in the department in that first year with Fraser was far more than anything we had known with the Whitlam Government. He would ring at any time of the night.

Years later when I spoke to Tammy Fraser about Malcolm’s plans, perhaps relaxing and spending more time at Nareen, his family property in western Victoria, she commented, “John, at Nareen he is bored shitless.” Seeing him in Cabinet and with his ministers I knew exactly what she meant. He wanted to relax but wasn’t sure how to. It was work, work, work. Outside politics he had few real interests.

At the first Cabinet I saw at first hand his great affection for black Africa. He was queried by a colleague about support which the Australian Council of Churches was providing for ‘guerrilla movements in Africa’. I was flabbergasted by Fraser’s response. He said that ‘the liberation movements in Southern Africa should be supported. Ian Smith [in Southern Rhodesia] is mad. I don’t just mean politically stupid. I mean he is clinically mad and the sooner he is got out of the way the better’. I was gasping. This was not what I had expected of a conservative Prime Minister.

A senior PM&C colleague later described to me how in a visit to South Africa in 1986 as a Co-Chairman of the Eminent Persons Group (EPG), Fraser called on Nelson Mandela in gaol. The EPG had been established by the Commonwealth Heads of Government to encourage a process of political dialogue to end apartheid in South Africa. Fraser described Mandela, to my colleague, as the most impressive man he had ever met. After 23 years in jail Nelson Mandela asked Fraser if Don Bradman was still alive. Fraser sent him a bat autographed by Bradman.

In the caretaker period after 11 November there were continuing and well-sourced reports about Indonesian troop movements which suggested a likely Indonesian attack on Dili. It came on 7 December 1975. Before the attack, however, Fraser had discussed the position in Timor and Indonesia with Tony Eggleton, who was the Federal Secretary of the Liberal Party, and me. Eggleton had been a press secretary to three Liberal Prime Ministers and the Director of Naval Public Relations. Fraser asked me to prepare a paper on the possibility of Australian military intervention in Timor against the Indonesians. He outlined two possibilities: either that Australia would intervene under a United Nations flag; or that Australia would do it unilaterally. He wanted information about the physical capabilities of the Australian defence forces to mount such a military operation against the Indonesians. Fortunately, Tony Eggleton was also opposed. He didn’t describe it as a mad hatter idea, but I think that is basically what he thought. I suggested it would be wise for Fraser to sleep on it before we did anything further. No further action was requested.

Later Fraser asked Alan Renouf, the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, to raise the Indonesian annexation of Timor in the United Nations. The department, however, was reluctant to intervene between Indonesia and Portugal. Renouf recruited Arthur Tange, the Secretary of Defence and former Foreign Affairs head, and respected by Fraser, to try to dissuade him. The problem was overcome by Portugal itself taking the matter to the United Nations.

In June 1976, Cynthia and I travelled with Fraser to Japan and China. At the last moment Susan Peacock, wife of the Foreign Minister, Andrew Peacock, could not make the trip and Cynthia was invited in her place. It was a great opportunity to be in Japan again and to see our oldest daughter, Susan, who was a Rotary student in Okayama in western Japan. In Tokyo, Fraser signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation between Australia and Japan, which Whitlam had first proposed to Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka, three years earlier. It was pleasant to see it signed after long years of bureaucratic delay on both sides. On the instructions of Fraser, I gave the Secretary of our Foreign Affairs Department a deadline for completion of negotiations.

In China, Fraser received a tumultuous welcome, very similar to the welcome Whitlam had received in 1973. In Whitlam’s case he was welcomed following the establishment of diplomatic relations. In Fraser’s case his anti-Soviet stand won him points with the Chinese.

The visit proved very eventful. By accident, the record of discussion of Fraser with Premier Hua Kuo-Feng was distributed by our Embassy to the media in error. The record highlighted Fraser’s criticism of the Soviet Union.

That was bad enough, but real turmoil was created by the leakage to the Melbourne Herald of a late-night discussion which Fraser held with his visiting party at the Guest House. The story alleged that Fraser had proposed a ‘four power pact’ comprising the United States, China, Japan and Australia, to contain the Soviet Union. On the Great Wall the next day, Peacock, the Foreign Minister and later Australian Ambassador to USA, almost out of breath waved a cable and yelled, “Prime Minister, Prime Minister, have you seen this?” It was a cable on the Melbourne Herald story. I was under suspicion. Warren Beeby in The Australian, referred to “unreconstructed Whitlamites” who were leaking to embarrass the Fraser Government. Fraser went out of his way to tell me on the Great Wall that he did not suspect me. He didn’t need to do that, but he was very aware of my difficult position, under pressure and in hostile territory.

On the return from Beijing, Fraser was irritated by the pretensions of the British in Hong Kong. Hong Kong police impounded the pistols of the Australian Federal police officers who were guarding him. In response he cancelled a visit to Governor MacLehose and rejected a cruise on his yacht around Hong Kong Harbour the next day. Steve FitzGerald, the Australian Ambassador in Beijing, and I, with our wives and staff had no problem taking over the cruise and sampling the Governor’s wines. When senior Hong Kong officials came later to Australia, Fraser had pleasure in instructing that the pistols of their police were to be impounded.

In the United States in July, I attended with Fraser his discussions with President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger. In Kissinger’s world of Realpolitik there was no place for waverers. You were either on the United States’ side or against. He detested the non-alignment of India. He said that he always arranged his itineraries to avoid any possibility that he might have to visit India. He adapted an old schoolboy story: ‘If you meet an Indian or a death adder on the jungle path at night, which do you kill first?’ For the Secretary of State of the most powerful nation on earth that was really something.

Fraser took a lively interest in all sorts of gadgets, especially the newest cameras and the radio telephone on his VIP aircraft. At a meeting of officials and private staff in the Hotel Okura in Tokyo, he brought in an amateur listening device he had acquired and, as a joke, placed it on the table. As the meeting started, ASIO officers dashed in shouting, “There is a listening device in here emitting a signal. Stop talking. Stop.” The toy was taken out to wry amusement. The meeting resumed. He was infatuated with intelligence and security gadgets.

His interest in intelligence gathering included checking on Whitlam’s abortive $500,000 fundraising from the Ba’ath Socialist Party in Iraq at the time of the 1975 election.

The go-between for the ALP and the Iraqis to raise the money was Henry Fischer, a Sydney businessman of central-European background and with contacts in the Middle East. Fischer took the story, unsolicited, to Murdoch in London. A reliable account of what then transpired is in _Oyster_, written by Brian Toohey and William Pinwell, and published in 1989. After action by the Commonwealth Government in the Federal Court in 1988, the text of the book was vetted by and negotiated with the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Having got the Iraqi scoop from Fischer, Murdoch swung into action. According to Toohey and Pinwell, Murdoch tried to get Fischer to persuade Whitlam to go to London to pick up the money personally and be secretly photographed in the act. Whitlam didn’t oblige. When Laurie Oakes broke the Iraqi story in the Sun News-Pictorial, Murdoch was scooped. In catch-up, he dictated his story for The Australian under the byline ‘A Special Correspondent’.

After the election of the Fraser government, the London ASIO representative was tasked from Canberra to interview Fischer. The ASIO reports distributed in Canberra made it clear that their primary information source was Murdoch. Fischer couldn’t be found. Murdoch was simultaneously playing the game from both ends: the source of the London ASIO reports that Canberra was reading and writing for The Australian.

But that was only the beginning of the story. Foreign Minister Peacock and his department were instructed to open an embassy in Baghdad as a cover for the posting of an ASIS agent, with the task of investigating Whitlam and his connections in Iraq. Alan Renouf, Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, and his Deputy, Nick Parkinson, together with Ian Kennison, Head of ASIS, were, to say the least, disturbed that this was not a legitimate intelligence-gathering exercise.

As head of Fraser’s department, I spelled out my concern to Kennison and others and told him that he should refuse to open an ASIS office. If he felt he couldn’t refuse, he should at least insist on a written direction from Peacock, his minister. The written direction was given, the Baghdad post opened, including an ASIS agent. The post was closed within 12 months.

Years later the Hawke government appointed Justice Hope to undertake a further judicial inquiry into intelligence and security matters. I briefed Hope on the extraordinary role of ASIO and ASIS in a party-political dispute over attempted fundraisings in Iraq.

Before I leave this episode, I should say that I believe Whitlam’s attempted fundraising from Iraq was out of character. Except for this one incident, I found him, almost to a fault, sceptical of people with money and mindful of the compromise that might be involved in accepting party donations from them. “Comrade, I will be beholden to no one.” Bill Hartley, his partner in the venture, a leader of the sectarian left in the ALP in Victoria, was as unlikely a collaborator as it was possible to imagine. In ‘normal times’ it would have sent all sorts of warning bells ringing and lights flashing in Whitlam’s mind. I can only conclude that after 11 November 1975, Whitlam was so distressed that his old caution and judgment on fundraising was thrown to the wind.

This is an updated extract from Things You Learn Along the Way, 1999 John Menadue

Tomorrow: Working with PM Fraser - burying White Australia - Part 4