Working with PM Fraser - parting words - Part 5 - Malcolm Fraser

November 23, 2025

John Menadue stayed on as the most senior public servant in the land, after the trauma of the Dismissal. In this five-part series he details what life was like working with PM Fraser. Given his closeness to Whitlam, some of his conclusions are surprising.

Malcolm Fraser became a firm opponent of white rule in Africa. Despite Maggie Thatcher he was determined to do what he could to end white rule in Southern Rhodesia.

On race issues it was likely that Fraser was influenced by his mother Una Woolf of Jewish descent. But I never heard him mention this ancestry. The angular and awkward Malcolm Fraser was also befriended and influenced by black Africans at Oxford.

Malcolm Fraser’s concern for human rights in Africa showed in the first cabinet meeting of the Fraser government after the dismissal of the Whitlam government. There had been a lot of media reports in Australia that money raised by the World Council of Churches for humanitarian aid in Southern Rhodesia was being diverted to assist the underground political and guerrilla opposition to Ian Smith, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia. In Cabinet the issue was raised by a senior NSW minister. I was really taken aback by Malcolm Fraser’s pungent response. He said that Ian Smith was not only politically culpable for racism in Southern Rhodesia, but that he was clinically ‘mad’.

In government from 1975 to 1983, Malcolm Fraser took up many of the human rights issues that Gough Whitlam had put on the agenda. Whitlam started the process to establish land rights for indigenous Australians, but it was Malcolm Fraser who had the first legislation enacted. From his western Sydney electorate of Werriwa, with migrants from so many countries, Whitlam laid the groundwork for multiculturalism. But it was Fraser who expanded and entrenched multiculturalism. SBS was established and settlement programs for migrants and refugees were co-ordinated and then well-funded following the Galbally Report.

Following piecemeal reform by Holt, Gorton and McMahon, Whitlam formally ended White Australia by legislation. But under the Whitlam Government the abolition of White Australia was never put to the test in the community. Migrant and refugee intakes in the Whitlam period were the lowest since the Great Depression.

Malcolm Fraser put the abolition of White Australia to the test by accepting tens of thousands of Indochinese refugees. Through the policies and programs initiated by the Fraser Government, including later family reunion, 250,000 persons of Indochinese background came to Australia.

Racism and opposition to foreigners is often a dormant but potent factor in public life, but Malcolm Fraser determined that we had a humanitarian obligation to the people who had fled Indochina. He didn’t wait for opinion polling or focus groups to decide what we should do. He gave us leadership. It wasn’t easy given our history of White Australia and the knowledge that fear of the foreigner, particularly Chinese could be so easily exploited. But with leadership, Malcolm Fraser showed that we all have generous instincts. With his leadership we responded because we knew in our hearts that he was right. If only we had that leadership today!

In my early days as head of Immigration the British High Commissioner called to confirm that Australia would continue to find a new home for “super grass”, British spies operating within the IRA. I had never heard about it. I was finding a lot of spiders under the rocks.

I spoke to Ian Macphee my Minister who said “no”. The High Commissioner then went over both our heads to Malcolm Fraser. Fraser was even more emphatic that we would not be taking “super grass” to solve a problem for the British in Northern Ireland.

My appointment as Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs in 1980 stemmed from Malcolm Fraser’s lively concern about racism. In my posting in Japan, I spoke to scores of community groups about Australia. On almost every occasion I would be asked about White Australia. It irritated me, particularly given Japan’s exclusivist policies on race and migration.

As I came to the end of my posting Malcolm Fraser was visiting Japan and he asked me what I wanted to do when I returned. I mentioned to him how White Australia had followed me all round Japan, so I told him I would like on return to Australia to do what I could to help bury White Australia. His response was instantaneous and to the point – ‘You’re on’! Within three months I was back in Canberra as Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs.

In that role I was able to continue to help expand the Indochina program. I also set about changing the Department that was culturally steeped in White Australia. I was quite public in what I was doing. Liberal Party backbenchers were concerned about my activities. But never did Ian Macphee, my minister, or Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, criticise or ask me to back off, even when graffiti was painted on the wall opposite my office in Belconnen, ‘Menadue = mongrelisation’. I should have photographed it before it was erased.

In his book _Dangerous Allies_, Malcolm Fraser gave credit to both Gough Whitlam and Doc. Evatt for their attempts to carve out an independent foreign policy for Australia. Fraser regretted that “we have significantly diminished our capacity to act as a separate sovereign nation” and “what faith can we as a nation having an ally that believes that is within its rights to remove a nation’s head of state”.

I don’t think Fraser would have had a bar of AUKUS and foreign bases in Australia. In Parliament on 11 March 1981, he said: “The Australian Government has a firm policy that aircraft carrying nuclear weapons will not be allowed to fly over or stage through Australia without its prior knowledge and agreement. Nothing less than this would be consistent with the maintenance of our national sovereignty.” The Albanese Government supinely accepts that the US ‘will neither confirm or deny’ that its vessels or aircraft are carrying nuclear vessels.

Malcolm Fraser was also active in attempting to develop Australia’s role within the Commonwealth of Nations. He saw the Commonwealth as an opportunity for a middle power like Australia.

It turned out that he and Gough Whitlam had more in common than they knew. Whitlam said that he hadn’t disagreed with Malcolm Fraser for 20 years! Several times he said to me that unlike Kerr, “Malcolm never deceived me. He was out in the open.”

Fraser delivered the Whitlam Oration in 2012. He opened the oration with ‘Men and Women of Australia’.

At the Sorry Day in Parliament House in 2008, former Prime Ministers were photographed together. With a walking stick, or ‘cane’ as Gough would have called it, in one hand – he put his other hand on Malcolm Fraser’s shoulder for support. It was quite moving to see the old combatants so close.

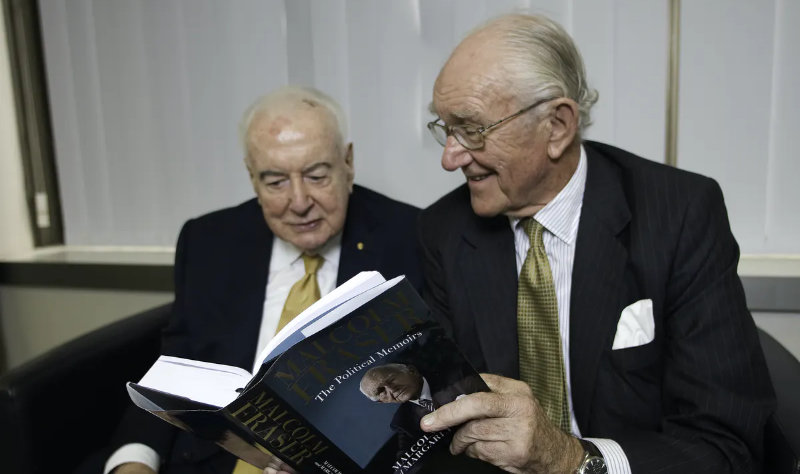

About three months before Gough Whitlam died, Malcolm Fraser called to see him in his Sydney office. He presented Gough with his book _The Political Memoirs_. He had inscribed in the book –

“Dear Gough, with great respect and affection, Malcolm.” My eyes misted over.

It had been a long and colourful journey for both, but there was clear respect and affection at the end.

Shortly after Gough Whitlam died, Malcolm Fraser commented: “Whitlam was a most formidable opponent in political terms but was someone I considered a friend. He had a sense of Australia’s identity and purpose as a nation, not as an appendage to other nations.”

The last contact I had with Malcolm Fraser was when he asked me if I was interested in joining a new Party he was considering. I declined.

Read the five-part series and more on our series of the Dismissal at 50.