Climate hot takes for 2025

December 18, 2025

Scientific evidence in 2025 showed global warming accelerating faster than expected, while emissions continued to rise and climate policy lagged dangerously behind physical reality.

Climate warming is a field of fast-changing physical realities – in many cases beyond scientific expectations – and gob-smacking new flood and heatwave and fire extremes, month after month, enhanced by a heating climate. And we are now ending a year when climate denial reached new peaks in the American Presidency and within our home-grown Liberal-National-Party coalition.

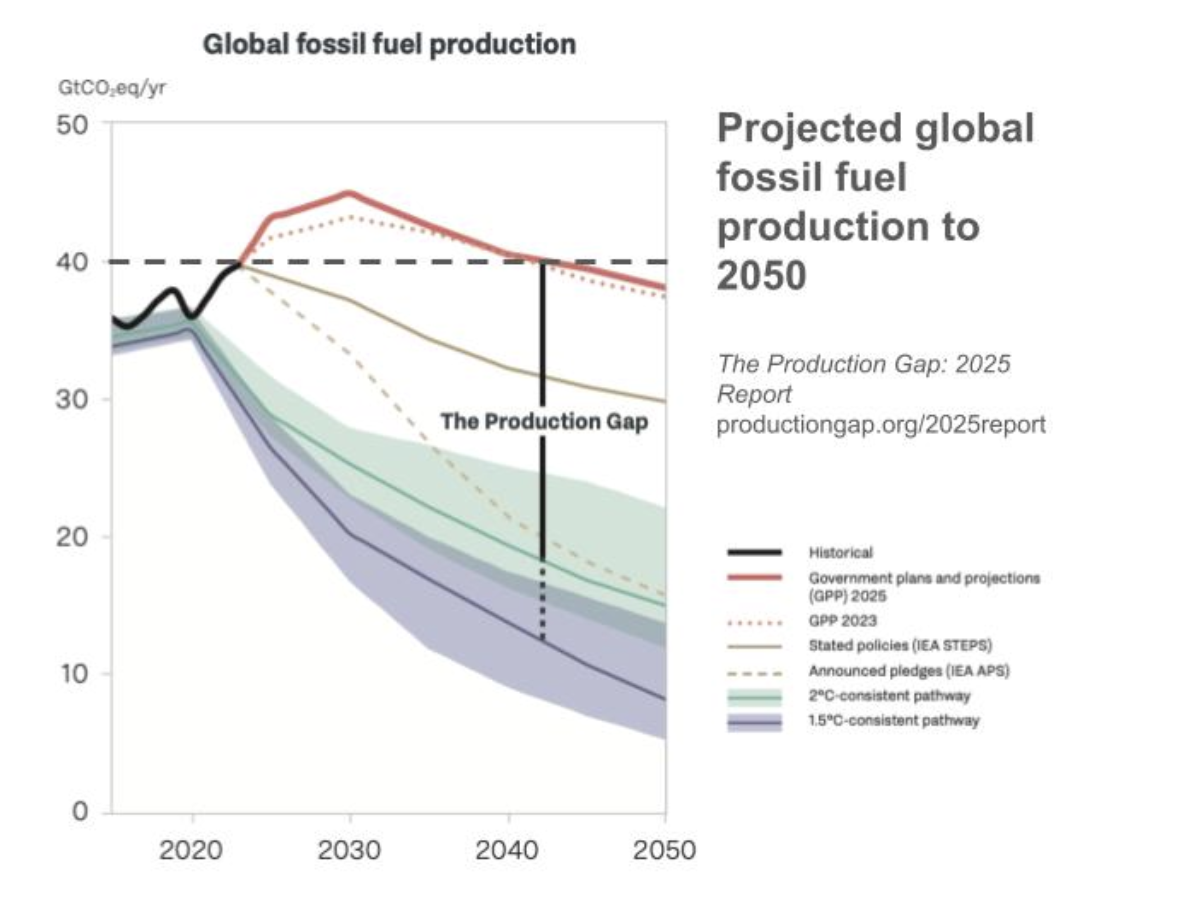

Fossil-fuel carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are expected to increase by 1.1 per cent in 2025 to reach a record high; the global average concentration of CO2 rose by 3.5 parts per million which was the largest increase since modern measurements started in 1957; and it is projected that fossil fuel emissions by 2050 will be barely lower than today, according to the 2025 Production Gap report (see diagram). In fact, both oil and gas supply are projected to continue rising till 2050.

This year, it was confirmed by scientists that the extraordinary jump in global average temperature in 2023 to 1.5°C was not a one-off, but indicative of a pattern of accelerated global warming. The 2024 year was 1.6°C; the first eleven months of 2025 was 1.48°C; and the three-year average will exceed 1.5°C.

It is unlikely that any future three-year average will drop below that figure. James Hansen, perhaps the world’s greatest living climate scientist, says that “averaged over the El Nino/La Nina cycle, the 1.5°C limit has been reached”.

The projections of continuing high emissions and the weakening of the carbon sinks in forests and in soils and permafrost means we are likely to exceed 3°C of warming. “We are potentially headed towards 3°C of warming by 2100 if we carry on with the policies we have at the moment,” says IPCC Chair Professor Jim Skea. And it may be a good deal higher than that.

Five years ago the late Professor Will Steffen argued that:

“Given the momentum in both the Earth and human systems, and the growing difference between the ‘reaction time’ needed to steer humanity towards a more sustainable future, and the ‘intervention time’ left to avert a range of catastrophes in both the physical climate system (e.g., melting of Arctic sea ice) and the biosphere (e.g. loss of the Great Barrier Reef), we are already deep into the trajectory towards collapse.”

The evidence over the last year only reinforces that conclusion. So how, in all of this, and thousands of new scientific papers, is it possible to select the “big” stories of 2025?

Running AMOC

Sometimes there are events in climate research and observation which are truly shocking – even to scientists. One was the extraordinary “big melt” of Arctic sea-ice in 2007 which led one leading glaciologist to exclaim that it was happening “100 years ahead of schedule.” And then there was the 2014 research which concluded that “a rapidly melting section of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet appears to be in an irreversible state of decline” and had passed a tipping point. Previously the IPCC had reported that Antarctica would likely be stable for a 1000 years, so it was a real eye-opener.

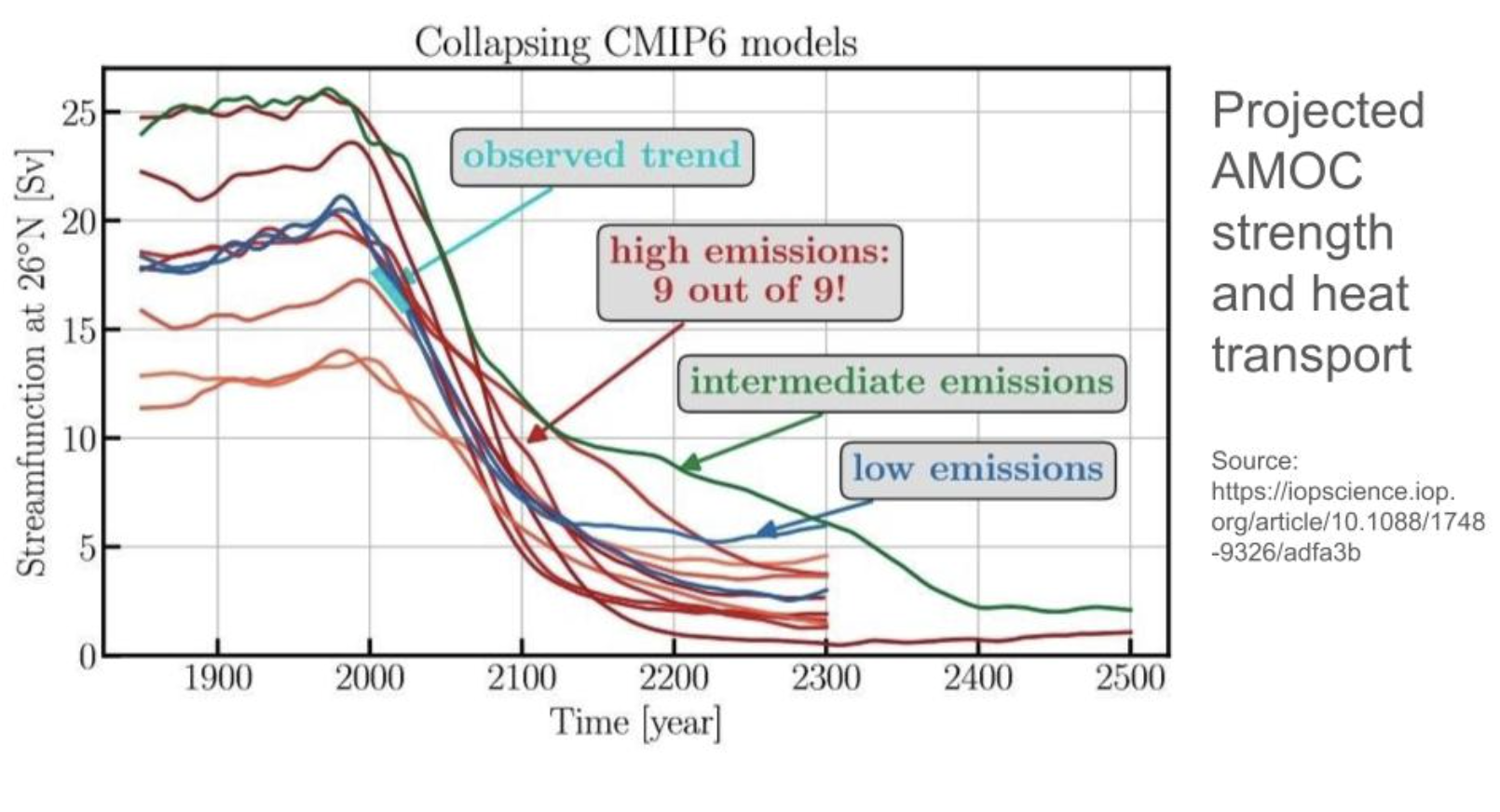

This year, it was research about the AMOC, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. New modelling showed it was at a point of collapse that would mean agriculture – and perhaps living – would become non-viable in north-western Europe. AMOC is the vast ocean circulation system across the breadth and depth of the Atlantic and from pole to pole that moves vast amounts of water; and also transports a huge amount of heat from tropical waters up the North American coast and on to northern Europe.

That this system could shut down or “collapse” in a hotter world was well established in theory and in climate history. It has already slowed by 15 per cent, but AMOC expert Professor Stefan Rahmstorf said that until recently he considered the risk of collapse this century to be less than 10 per cent. Then came new research by Ramstorf and two colleagues, 'Shutdown of northern Atlantic overturning after 2100 following deep mixing collapse in CMIP6 projections'. Using standard climate models with high emissions – the path we are presently on – the research showed the AMOC shuts down in all nine models that ran past 2100, and is well on the way by 2100, having commenced at the end of the last century. The collapse is likely initiated by surface warming.

Ramstorf says that “the AMOC tipping point where the shutdown becomes inevitable is probably in the next 10 to 20 years or so,” and he gave a compelling, short AMOC presentation at the Helsinki Atlas 2025 conference. Other research showed that the tipping point where the AMOC breaks down is also found in a high-resolution ocean model.

Whilst the collapse would not be complete till the mid-2100s, the implications in the shorter term are profound for some European states. Iceland has designated the potential collapse of AMOC a national security concern and an existential threat, enabling its government to strategise for worst-case scenarios. Climate Minister Johann Pall Johannsson told Reuters: “It is a direct threat to our national resilience and security… this is the first time a specific climate-related phenomenon has been formally brought before the National Security Council as a potential existential threat.”

Likewise, The Economist reported with alarm that:

“A complete AMOC shutdown could see Brussels hitting -20°C (-4°F) in a bad winter. In Oslo the figure would be almost -50°C (-58°F). Average rainfall in parts of northern Europe would drop precipitously; according to one estimate as much as 80 per cent of England’s arable land would no longer be farmable without irrigation. Storms would get worse. An AMOC collapse would push the band of rain which girdles the tropics towards the south. That would be very bad for the African countries on the south edge of the Sahara; it could also be devastating to the Amazon.”

When AMOC collapse challenges European foundations, including the viability of nations and states, and of the EU and NATO, this moves climate from the realm of environmental, left-right culture wars and into the heart of the matter: human security, social breakdown, mass displacement and death.

Accelerating warming skewers the Paris framework

The international climate policy-making deal at COP21, the Paris Agreement, identified a new climate goal of 1.5°C, which required “net-zero by 2050” emissions, based on modelling to “overshoot” the target and then cool back to it by 2100, driven by voluntary, unenforceable Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to emission reduction by member states.

This was based on modelling which showed 1.5°C of warming would be reached around 2040. And fossil fuel reductions didn’t get a mention. The framework was always a fantasy, and accelerating warming and new research has now made that clear to anyone with their eyes open.

First, as noted above, emissions and CO2 levels are still rising and emissions by 2050 are looking more like 100 per cent of the 2015 level, rather than “net zero”. NDCs are a free kick to petrostates, and they have treated them as such.

Second, with 1.5°C arriving 15 years earlier than anticipated in Paris – 2025 versus 2040 – the “net zero” goal would also have to move forward fifteen years to 2035, but that necessity has passed not one policymaker’s lips.

Third, overshoot is now ringing more alarm bells in the scientific community. Extinctions caused by overshoot are one thing that can’t be restored: once a species is extinct or an ecosystem destroyed, lowering the temperature won’t bring them back. Now researchers warn that:

“Global and regional climate change and associated risks after an overshoot are different from a world that avoids it… the possibility that global warming could be reversed many decades into the future might be of limited relevance for adaptation planning today [because] temperature reversal could be undercut by strong Earth-system feedbacks resulting in high near-term and continuous long-term warming… Only rapid near-term emission reductions are effective in reducing climate risks.”

Fourth, 2025 has brought more evidence that 1.5°C is far from safe. It has been shown that the Paris Agreement target won’t protect polar ice sheets, that overshooting climate targets could significantly increase risk for tipping cascades, and that of ten major climate subsystems (such as polar ice, Amazon etc), six show large-scale abrupt shifts across multiple models at warming of 1.5°C.

Fifth, the heart of the climate challenge is ending the use of fossil files. No ifs, no buts. But again at the COP30 climate policy-making farce this year in Belem, Brazil, petrostates moved to block any mention of fossil fuel phase-out in the final resolution, as they have for three decades and are likely to for another three if the COP process should stagger on for that long.

For half the states there, and the community-based advocates at Belem, this was an outrage, and they expressed their determination to go on building a coalition of the willing around the demand to plan and end the use of fossil fuels. But this did not happen at the official COP proceedings, but on the sidelines and despite it.The official COP process is dead; even COP regulars now say that UNFCCC consensus governance means it will always fail.

This big initiative of phasing out fossil fuels can more fruitfully grow outside the prison walls of the COP than inside. From now it will be easier and cheaper and more effective to get people together without the COP pageantry and the 1600 fossil fuel lobbyists in attendance, and organise independently and away from a deadly charade. It will also be easier to adopt measures as a group, such as climate-focused foreign and trade policies, border carbon taxes, and the like.

Facing collapse, a time for climate interventions?

In their annual State of the Climate Report, entitled in 2025 A planet on the brink, William Ripple and his colleagues warned that:

“We are hurtling toward climate chaos. The planet’s vital signs are flashing red. The consequences of human-driven alterations of the climate are no longer future threats but are here now. This unfolding emergency stems from failed foresight, political inaction, unsustainable economic systems, and misinformation. Almost every corner of the biosphere is reeling from intensifying heat, storms, floods, droughts, or fires. The window to prevent the worst outcomes is rapidly closing.”

In 2025, it has been noticeable that the idea that we are heading towards 3°C or more – with a global food-and-water crisis triggering social conflict, state failure, large-scale displacement, war and systemic collapse – has become more mainstream.

For example, at a UK National Emergency Briefing on 27 November 2025, an audience of 1250 including 100 parliamentarians heard from ten leading UK scientists, who did not mince words. Professor Kevin Anderson told the briefing:

“We are going to see a rise of about 2°C by the middle of the century. But now there is a small but very real risk that we could hit 4°C by the end of the century. The prospects of 3°C and 4°C of warming are absolutely dire. We cannot risk that at all. It’s extreme and unstoppable and beyond any safe zone that has nurtured civilisation. We are going to be seeing unprecedented societal and ecological collapse. We are going to see escalating geo-political instability and rising military tensions. And there will be no real economy to talk about. There is no ‘reduction in GDP’. We’d be looking at systemic collapse.”

We are already at 1.5°C, with some tipping points passed, others on the brink and abrupt change hovering. Sir David King, the former UK Chief Scientist, has made the case for climate interventions because “rapid emissions reduction is no longer sufficient to avoid an unmanageable future for mankind. We also must have the capability to remove greenhouse gases at scale from the atmosphere, and to repair those parts of the climate system, such as the Arctic Circle, which are passing or have passed their tipping point”. The need for large carbon drawdown is well understood, and climate repair including direct cooling – for example by solar radiation management (SRM) – is no longer just a theory.

At least two organisations are now either deploying atmospheric cooling techniques at small scale ( makesunsets.com) or actively testing solar radiation management techniques ( stardustsolutions.com), so the cooling governance debate is no longer an abstract one.

UK scientists are launching outdoor geoengineering experiments as part of a £50m government-funded programme run by Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria).

In May, Cambridge hosted the Arctic Repair Conference 2025, a pioneering conference hosted by the Centre for Climate Repair, in association with the University of the Arctic, with a focus on innovative climate engineering techniques designed to combat the rapid changes taking place in the Arctic. The podcaster Nate Hagens asked Will we artificially cool the planet? The science and politics of geoengineering, and scientists published a Call for more climate intervention research.

Perhaps the most interesting event was in Helsinki, hosted by Operatio Arktis, a Finnish youth advocacy organisation. ATLAS2025 aimed to address “critical security and economic challenges by bringing together key decision-makers, scientists and thought leaders to prioritise tipping point risk management from the perspective of Finland, the Nordic countries and the global community, and in anticipation and prevention, technological interventions and effective approaches”.

Attendees included senior government officials, activists, scientists and representatives of the traditionally Sámi-speaking indigenous people inhabiting the region of Sápmi, which includes large northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland, and of the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

A focus of the conference was the need for climate interventions and cooling options such as solar SRM to preserve the Arctic, and outcomes included:

“A. Develop effective governance. Currently, we lack international regulation for SRM, which is problematic given the unequal distribution of capacity in the world. B. Support responsible research on the benefits and risks of SRM. Elevate research efforts which follow the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and co-create projects in a way that serves stakeholders and public interest. C. Engage and communicate with a broad range of stakeholders about the potential risks, benefits, and distributional effects of SRM. Create space for critical and also principle-based conversations.”

Such an event and outcomes were probably unimaginable a couple of years ago, but it is one example of how the impending crisis and the imminence of abrupt and cascading change is spurring new climate conversations.

As for Australia, there is barely a whisper about such matters, and the opposition is at war with the laws of physics and chemistry, whilst the government solidifies Australia’s position as the third largest exporter of fossil fuels by handing out new coal and gas licences.