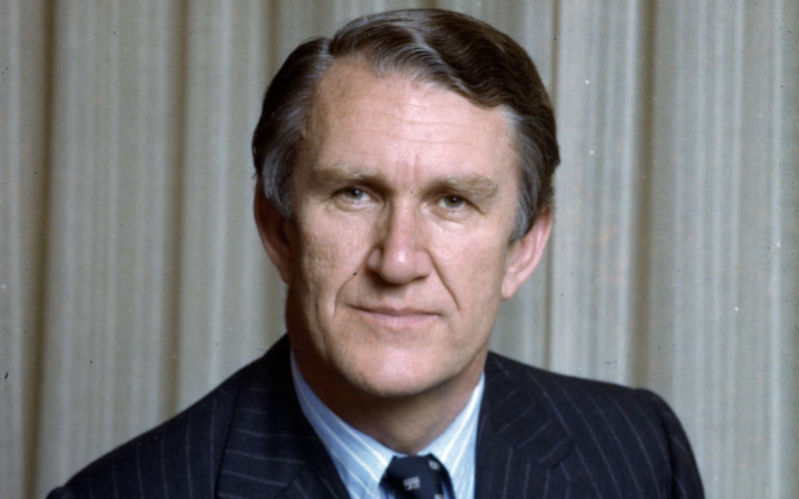

Malcolm Fraser: a decent man committed to an independent Australia

December 4, 2025

Personal experience and recent reflections challenge the popular caricature of Malcolm Fraser, revealing a former prime minister increasingly willing to defy orthodoxy in defence of sovereignty, justice and independence.

I was moved reading John Menadue’s recent series, “ Working with PM Fraser”. It brought back memories of my brief but productive collaboration with Malcolm Fraser in his final two years.

I first met Malcolm Fraser in January 2013. I had spent part of my childhood growing up in Ararat in the electorate of Wannon, for which he was the local MP. I can remember sitting bored in our family vehicle as a six- or seven-year-old waiting for my father to finish a constituent meeting with “the prime minister” in his electorate office. I also remember, from hearing various adult conversations over the years, that Malcolm Fraser had cried when he lost the 1983 election; he had said “life wasn’t meant to be easy” (my mum loved quoting that one to us kids when we whinged); and something about him losing his trousers somewhere. All of this added up, in my mind, to a caricature of the man.

By the time I met him, however, I had developed a deeper appreciation of Fraser based on his more recent activities, rather than my perception of his time in politics. My party, the Citizens Party, has always focused on issues relating to Australia’s national sovereignty, and as Research Director I had noticed Malcolm Fraser taking strong positions that we agreed with on issues such as opposing Canadian media magnate Conrad Black’s takeover of Fairfax, opposing the Iraq war, and speaking out against Australia’s appalling mistreatment of refugees. The issue that led to our meeting was his outspoken opposition to the early talk of war against China.

In 2012, the Citizens Party published an issue of our New Citizen newspaper in which we detailed the presence of US bases and facilities in Australia, and identified the political identities who were openly talking of war with China. The strongest quotes in that feature against this emerging agenda were public statements by Malcolm Fraser, so we mailed him a copy and he agreed to meet.

In our first meeting, which included Citizens Party founder Craig Isherwood, we discussed the Asia Pivot announced by Barack Obama in 2011, which was premised on a supposed China “threat”. Mr Fraser showed he had a deep understanding of the historical origins and legal issues around tensions in the South China Sea.

Unprompted, he raised Zionist leader Isi Leibler’s attacks on him for his support for Palestinians. This was common ground, as our party had also experienced being attacked by Isi Leibler. He showed he would not be intimidated, leaving no doubt in my mind as to what position he would have taken on the Gaza conflict in the last few years.

Another unexpected area of common ground was the financial system. As we were speaking about the hangover from the global financial crisis, Fraser commented, “Repealing Glass-Steagall was a mistake.” Glass-Steagall was the 1933 US law that had separated commercial banks with deposits from speculative investment banking; its repeal in 1999 had fuelled the explosion of derivatives speculation that had imploded in 2008. At that time our party was in the middle of a major campaign for a Glass-Steagall separation of Australia’s banks. Fraser became an enthusiastic recruit to that campaign, and even wrote a submission to the 2014 Financial System Inquiry calling for an Australian Glass-Steagall law. As John Menadue observed, he was no Thatcherite.

Perhaps the most dramatic episode in our collaboration was immediately following the 22 February 2014 coup in Ukraine, when US-backed protesters drove out the Yanukovych government. On 3 March he wrote a powerful op-ed in The Guardian, Ukraine: there’s no way out unless the west understands its past mistakes, which denounced the USA’s broken promise not to expand NATO eastward. We quoted him in a Citizens Party release criticising then-PM Tony Abbott’s response to the events, which prompted the Russian news agency Tass to contact me asking for an interview with Fraser. Not many people would have been prepared to speak to Russian media in those weeks, but when I passed on the request Fraser didn’t hesitate. The resulting half-hour interview on RT’s Worlds Apart was significant, in that a senior statesman of the west sheeted home blame for the conflict on US-NATO policy. (Read a transcript of the interview by P&I contributor Susan Dirgham).

In a meeting soon after that, he was excited by the impending publication of his book, Dangerous Allies, in May 2014. He was especially proud of the promotional kicker for the book: Australia needs America for security, but Australia only needs security because of America.

In my last meeting with Malcolm Fraser, he mentioned he had been in discussion with John Menadue about starting a new political party. John mentioned this discussion in his recent series but said he had declined when Fraser queried whether he would be interested in joining such a party. As I told John last week, I got the impression from my discussion with Fraser that he considered it a real possibility, so he may not have taken John’s response as the last word and intended to keep working on him.

In early 2015 I phoned Fraser and asked him to speak at an international conference the Citizens Party planned for March 2015. He agreed but cautioned that he first had to see how he recovered from an operation he was scheduled to have a few weeks before the conference. Sadly, he didn’t survive the operation. We opened that conference with a tribute to Fraser and his abiding commitment to a truly independent Australia.

From my personal experience, which I feel John Menadue’s series confirms, Malcolm Fraser was a thoroughly decent man, who in person was different to the superficial caricature of a ruthless politician that defines him to many Australians due to the tumultuous political events of the 1970s.

End note: The television coverage following Malcolm Fraser’s death included interviews in which he acknowledged being emotionally reserved. Due to his austere, reserved demeanour I could not bring myself to call him anything other than Mr Fraser, but I did get to see a crack in that demeanour. In a meeting with him one day I nearly died with embarrassment when my SMS notification went off, which was a very loud Woody Woodpecker laugh. As I fumbled to put my phone on silent, Fraser gave us a little grin and told us a story of how he had been at a family event and all his grandchildren were absorbed in their phones. He asked what they were so interested in and they said Twitter, so afterwards he signed up to Twitter himself. When he next saw his grandchildren, he asked them how many followers they had, and each answered they had a few hundred. Smiling broadly, he told us that he had boasted: “I have 30,000!”