MYEFO leaves the hard work on inflation, debt and budget repair undone

December 19, 2025

The latest MYEFO shows only marginal improvement in the budget outlook, while deficits persist and fiscal settings continue to complicate the Reserve Bank’s task.

Wednesday’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) – the half-yearly review of the 2025-26 Budget presented back in March, just before the most recent Federal election was called – does little to ameliorate the challenge now facing the RBA in getting inflation back into its 2-3 per cent target band without back-tracking on at least some of the three reductions in interest rates which it implemented earlier this year.

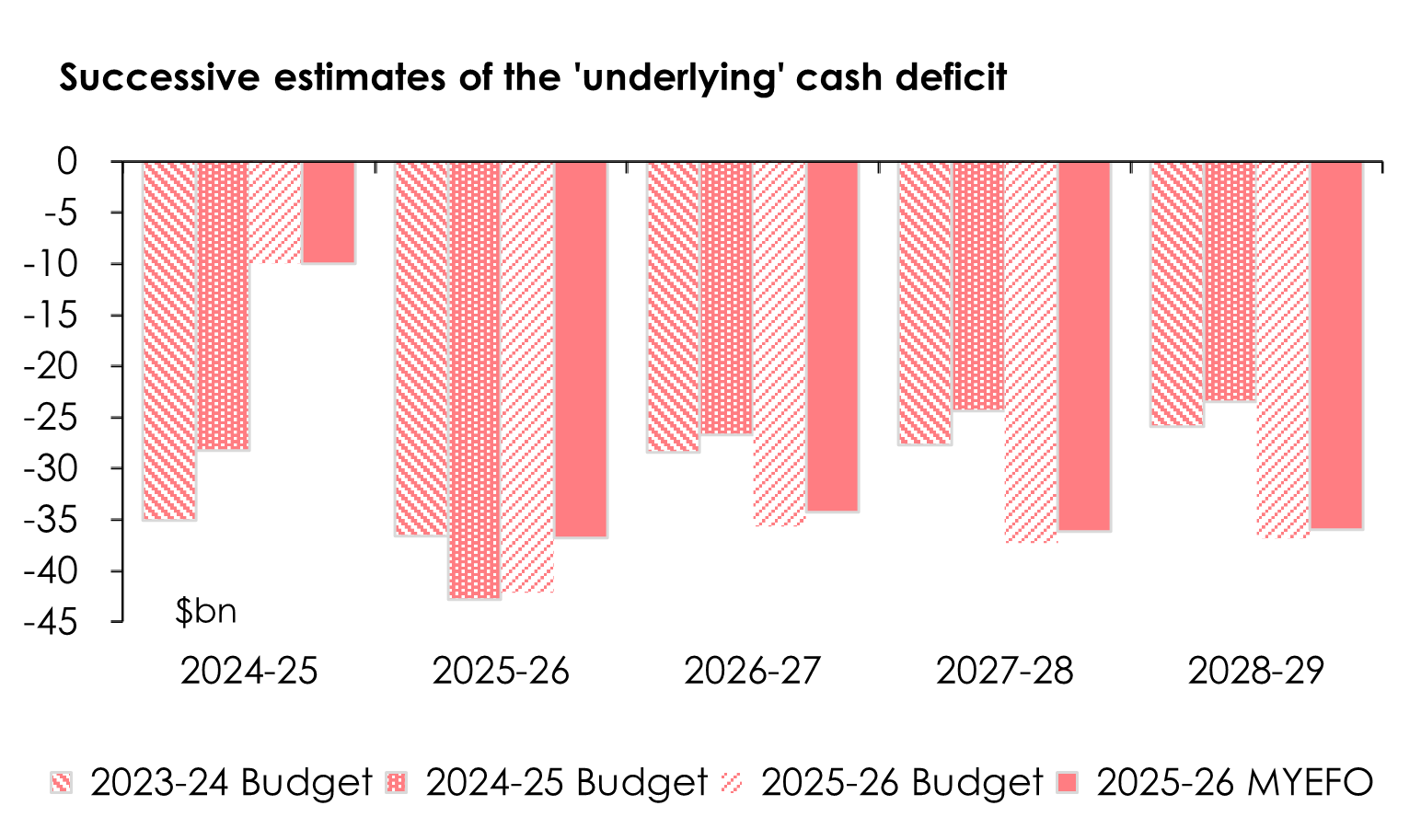

Treasurer Jim Chalmers and Finance Minister Katy Gallagher are congratulating themselves for foreshadowing ‘underlying’ cash deficits totalling $143.2 billion (equivalent to an average of 1.2 per cent of GDP) over the four years to 2028-29, $8.7 billion (or 0.1 pc pt of GDP) less than had been projected in the March Budget.

Of that improvement, $2.2 billion comes from policy decisions – and, as they note, this is the first time in eight years that policy decisions have resulted in an improvement rather than a deterioration in the ‘bottom line’. That $2.2 billion comprises of $3.8 billion of net savings in payments (none of which occur until the 2027-28 financial year – policy decisions actually increase payments by $1.8 billion in 2025-26 and 2026-27), partly offset by $1.6 billion in reductions in receipts, largely stemming from the changes to the Government’s plans to increase tax on large superannuation balances announced in September.

The remaining $6.2 billion in improvements to the ‘underlying’ cash balance over the four years to 2028-29 comes from what budget documents call ‘parameter variations’ – that is, changes to forecasts and other assumptions underpinning the forward estimates of payments and receipts – with the former being revised up by $35.1 billion over the four years to 2028-29 and the latter by $41.3 billion (as in previous years, in large part because commodity prices have remained higher than Treasury’s very conservative assumptions, resulting in higher company tax collections from mining and energy companies).

The Government congratulates itself for ‘banking’ all of the upward revisions to revenues (that is, directing them towards reducing the deficit), for (it says) the first time “in more than a decade and a half”.

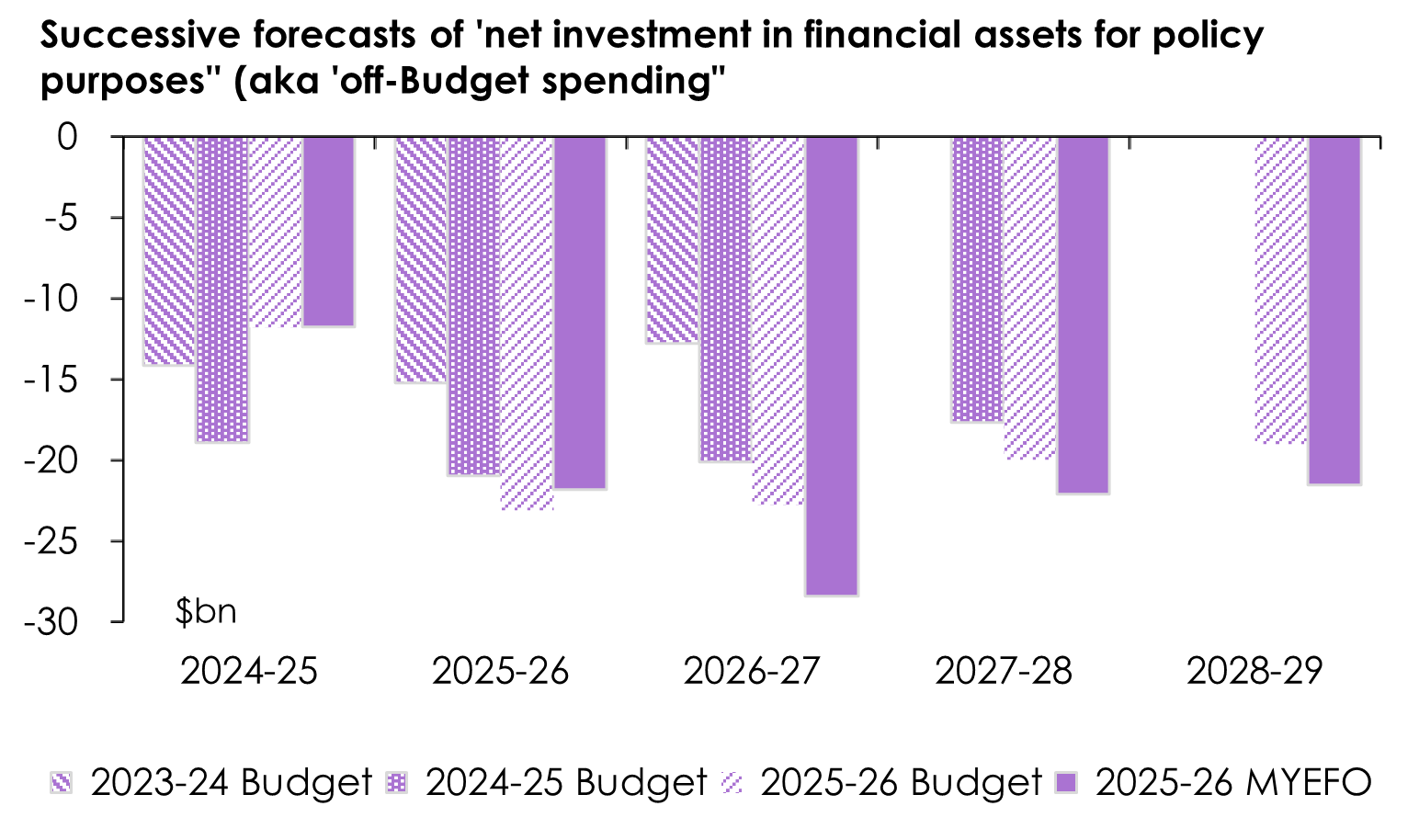

So far, so good – albeit in very small quantities. But the improvement in the so-called ‘underlying’ cash balance has been more than offset by increases in what budget documents call ’net investments in financial assets for policy purposes’, and what many journalists and analysts have taken to referring as ‘off-budget spending’ – totalling $9.0 billion over the four years to 2028-29.

Of this amount, at least $5.6 billion is attributable to ‘policy decisions’, including $2.6 billion in additional concessional loans to community housing providers, $2.0 billion in concessional loans “to support states, territories and industry to deliver up to 100,000 new, well-located dwellings reserved for sale to first home buyers” (one of the Government’s 2025 election pledges), and $1.0 billion for the Regional Investment Corporation to “deliver new concessional loans to farm businesses and drought-affected farm-related businesses” (among other things).

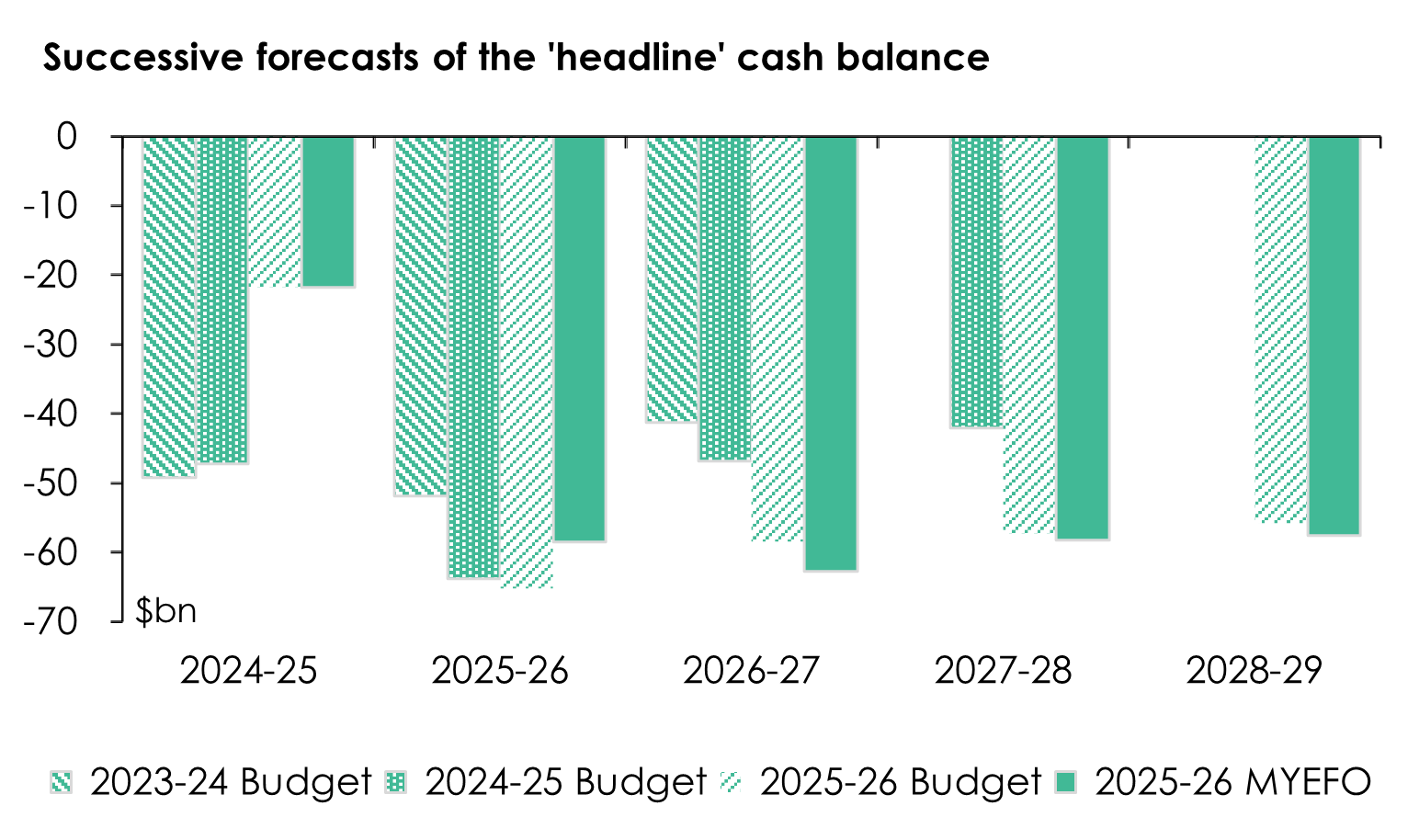

As a result of this increased ‘off-budget’ spending, the Government will incur headline cash deficits totalling $237 billion over the four years to 2028-29 - which is marginally ($291 million) more than had been forecast in the 2025-26 Budget (see chart below).

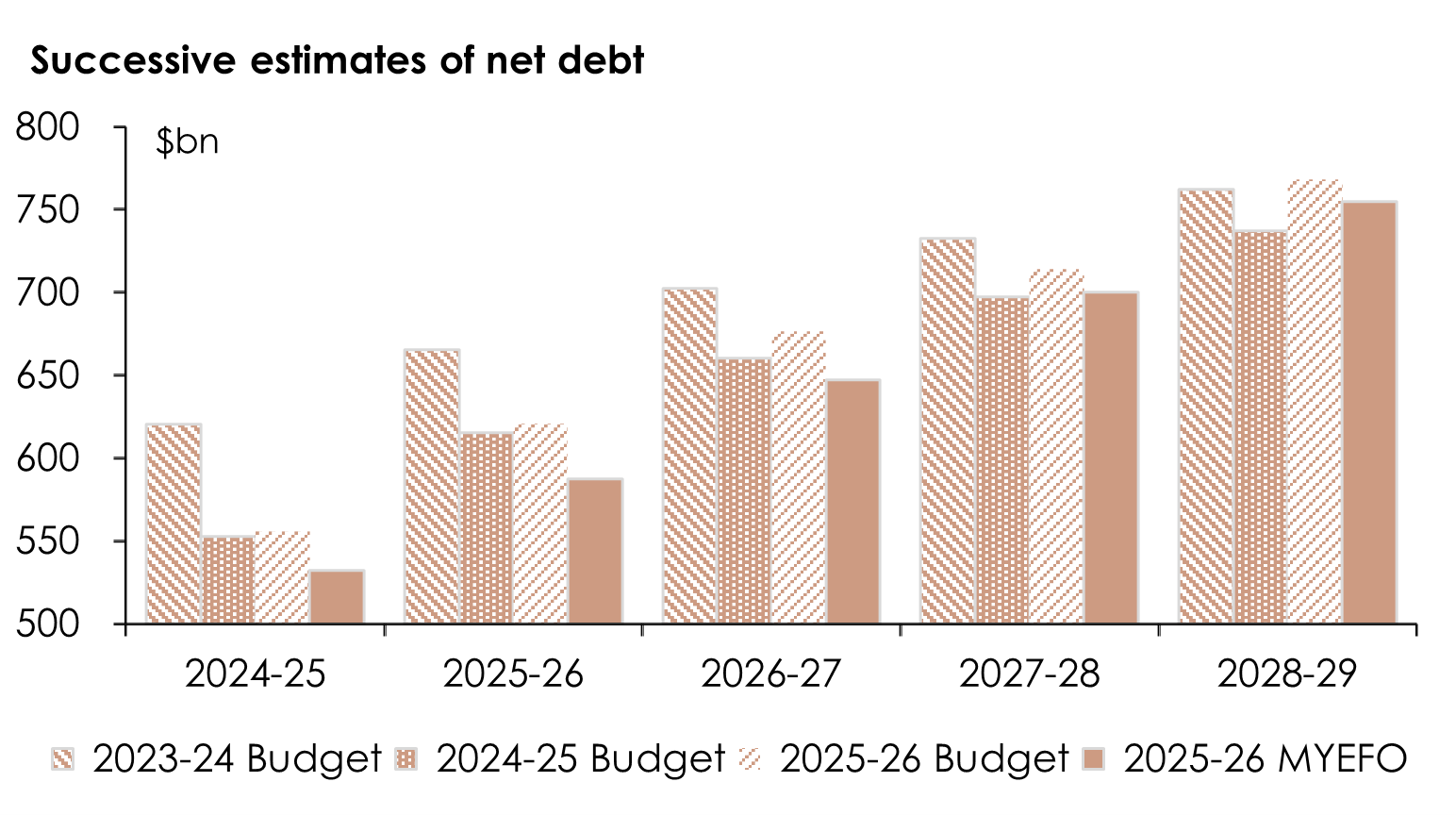

And it is the headline cash balance not the ‘underlying’ balance, which for the past 30 years has been taken as ’the’ preferred measure of the Budget ‘bottom line’ – which is the principal driver of changes in net debt. And MYEFO forecasts that net debt will rise by $222.5 billion over the four years to June 2029, which is $9.9 billion more than had been projected back in March. The only reason that the forecast level of net debt in June 2029, of $754.8 billion, is $13.4 billion lower than the corresponding forecast in the March Budget is because the starting point – the level of net debt as at 30th June 2025 – was $23.6 billion lower than had been anticipated in the March Budget.

The point of all this is that the Government really hasn’t done anything significant to wind back the contribution that its transactions with the rest of the economy are making to sustaining growth in aggregate demand (a contribution which is better captured by the ‘headline’ as opposed to the ‘underlying’ cash balance – by which measure the Government hasn’t done anything at all to reduce its contribution to growth in aggregate demand), thereby making it less challenging for the RBA to bring aggregate demand into line with aggregate supply in order, in turn, to bring ‘underlying’ inflation back into the 2-3 per cent target band.

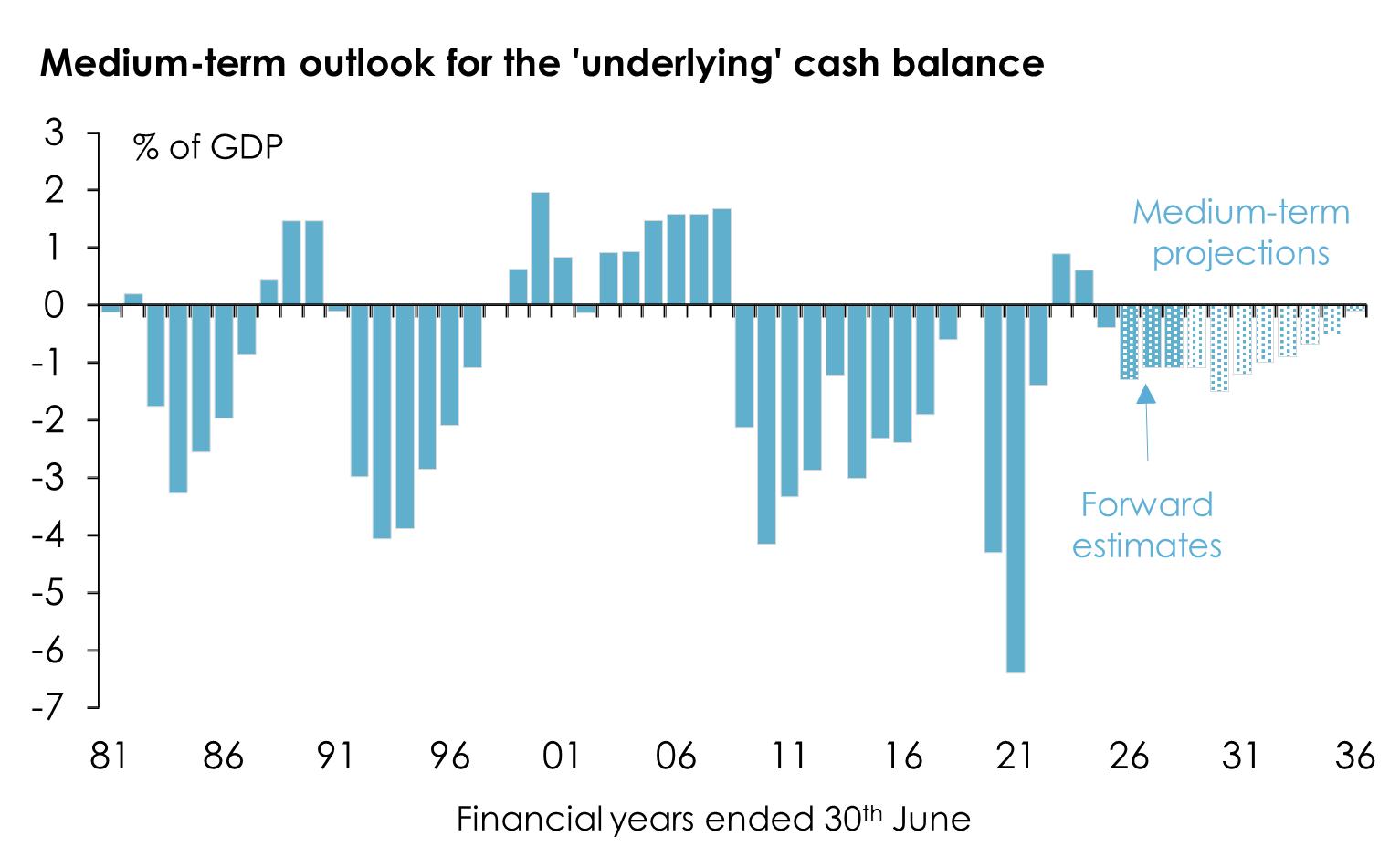

Nor has the Government really done anything to improve the medium-term outlook for the Budget, which still shows budget deficits persisting into the middle of the next decade.

In fact, if you want to be really picky, MYEFO forecasts that there will be an ‘underlying’ cash deficit of just under $5 billion (0.1 per cent of GDP) in 2035-36, whereas the March Budget forecast that the ‘underlying’ cash balance would be zero in a decade’s time. (Neither the Budget nor MYEFO makes any projections for the ‘headline’ cash balance beyond the end of the four-year forward estimates period – or at least the Government doesn’t publish them, although Treasury must make them internally in order to be able to generate medium-term projections of net debt).

And the only reason the ‘underlying’ cash balance declines at all after 2028-29 is because of ‘fiscal drag’ – that is, taxpayers being forced into marginal tax rate brackets because of the non-indexation of the personal income tax scales, something which (as former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry has repeatedly pointed out) will disproportionately impact younger wage and salary earners.

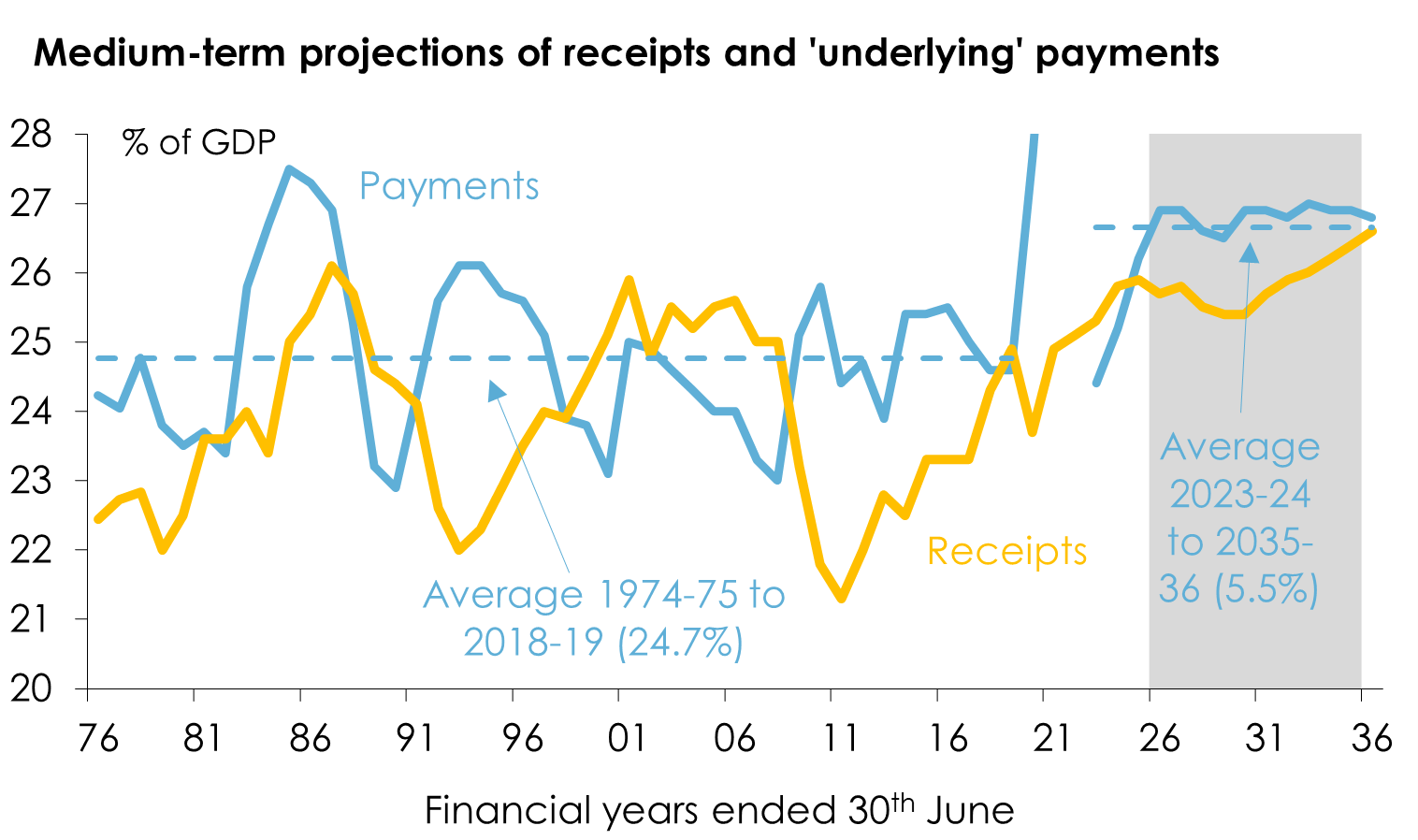

Yes, I get that there are inexorable pressures on the spending side of the Budget, arising from (in particular) the ongoing ageing of the Australian population, demands on the NDIS, the need to spend more on defence (which to me arises not from the need to appease the Americans, but rather because we can no longer regard the Americans as trustworthy and reliable allies and defence partners) and from the escalating burden of interest payments. As I’ve written before, that’s been plainly evident since the last Budget of the previous Coalition Government in 2022.

But this Government has been unable or unwilling to reduce spending in other areas in order to make room for this additional spending, or, alternatively, to increase revenues in order to pay for it. That’s in large part because the Government hasn’t sought, at either of the past two elections, a mandate from the electorate to undertake either spending cuts or tax reforms that would pay for the additional spending on health, aged, disability and child care which the electorate clearly wants, the additional spending on defence which both sides of politics thinks the electorate should have (whether they want it or not), and the additional spending on interest which is unavoidable as a result of all the debt that successive Governments have run up since the global financial crisis and (on current projections) will continue to run up over the next 10 years.

Again, I understand the Prime Minister’s reluctance to do anything that the Government hadn’t said it would do during the most recent election campaign. But to date, there’s not much if any evidence of any great willingness or enthusiasm on the part of the Prime Minister, or the Treasurer, to ‘argue the case’ for a mandate for ‘budget repair’ or ’tax reform’ ahead of the next election, due by May 2028, at which – given the huge majority it won in the House of Representatives at this year’s election – it is more likely than not to get a third term.

And in the absence of that, the Government’s budgetary position is likely to remain a risk to the outlook for interest rates, and a drag on Australia’s potential growth performance.