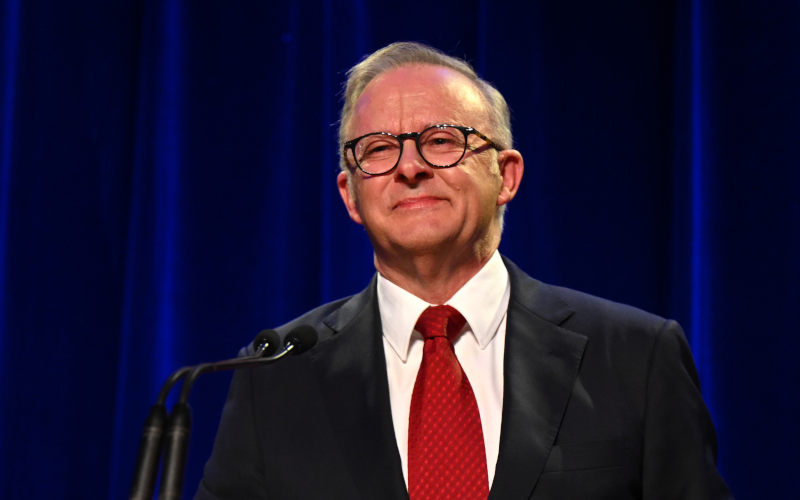

How the Albanese government kept “jobs for mates” alive

December 4, 2025

The Albanese government promised to end political patronage in statutory appointments, but has instead chosen a non-binding framework that preserves ministerial discretion and limits accountability.

The Albanese government has decided not to restrict its flexibility to appoint mates to statutory officer positions. What a surprise.

The ALP rightly and self-righteously criticised the Morrison government for its wholesale political patronage. Its habits were severe enough in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal to cause its abolition and replacement.

As a matter of principle appointments to statutory positions should be as far distant from politics as possible because the fundamental reason for their existence is to perform functions removed from government influence. The ABC or the SBS should not be subject to Pravda-like political direction.

Many governments have not been so sensitive, although Morrison’s took things to rarely seen extremes.

In a flush of reformist enthusiasm after it was first elected the Albanese government vowed to knock off the “jobs for mates” habits. It engaged Lynelle Briggs, a former Public Service Commissioner, to advise on what to do so.

Her report was signed off in August 2023 and until this month it was kept under the tightest of wraps because it was alleged to be a Cabinet document. That’s nonsense, of course, as standard good practice is for reports to be made public and used for consultation prior to final government decisions. Clearly Briggs’s report caused enough “trouble at mill” for citizens to be excluded from having a say on it prior to its being shelved.

On 2 December, the Government released the report and indicated, if in not so many words, that it was rejecting all its significant recommendations, including that procedures for statutory appointments should be legislated to provide strong protections against ill-intentioned governments and ministers.

Briggs’s report contains too much fluff, gets too much into the weeds and, on the critical point, sows the seeds of its destruction.

It carries on about having “a champion team…rather than a team of champions”, “finding the spark of behaviours and skills that ignite opportunities” and getting “new people to bring about generational change.” Such distracting rhetoric is unhelpful especially when it is augmented by the populist spiel that statutory appointments “should reflect the diversity of society”, whatever that means. What’s important is that appointments are made on the basis of who is best able to do the job and if that means there are no youths or senior citizens or Tasmanians on the Reserve Bank boards, then too bad.

But to get to the nub: the risk of the politicisation of statutory appointments is in proportion to the extent of ministerial discretion in making them, all other things being equal. This is where the Briggs report collapses, allowing the government to set it aside.

Briggs recommends that ministers be advised on appointments by independent committees. The reports of these committees would then be used to make recommendations to the prime minister about appointments, however ministers could ignore panels’ reports and recommend a “direct appointment” of whoever they wish although giving reasons for doing so which would “be made publicly available on announcement.”

In essence this is the arrangement that now applies for appointments to the ABC and SBS boards. It has not prevented jobs on these boards that owe more to political alignment than merit. The requirement for ministers to give public explanations when they have not followed the recommendations of advisory committees has been an ineffective discipline. When Prime Minister Morrison brought forth Ita Buttrose to be the chair of the ABC board, he simply said “Oh, everyone knows Ita”. Many probably did and that was enough for them.

Briggs has recommended a system of proven fallibility and in doing so has provided ministers with the capacity to do whatever they want without the slightest political or any other penalty.

So why has the government rejected her recommendation?

Well, what would be the point of legislating statutory appointment procedures of proven unreliability which ministers can easily work their ways around without the discipline of political penalty? As there is none, Briggs has provided the government with the opportunity to reject her key recommendation and be logical in doing so.

In place of Briggs’s recommendations, the government has brought forth a “ Government Appointments Framework”. It is to have no legal backing and is a masterpiece of the permissive containing vast acreages of ice for ministers to skate on. It repetitively suggests ministers should only do things that are “appropriate and proportionate”, code that requires no imagination to crack.

Often political interests and the public interest coincide but where they do not there can be no surprises about guessing the winner. And that’s what we have here.

Politicians can be eloquent about the need for merit in appointments to public offices and the need to avoid the politicisation of statutory positions where independence from politics is critical. In the commonwealth, these sensitivities are often observed, if in varying degrees. Too often, though, merit is subordinated to the desire to give jobs to mates. Those temptations can best be minimised by restricting ministers to selecting appointees from lists of candidates recommended by independent advisory panels.

This was the essence of an excellent Bill prepared by the member for Mackellar in the House of Representatives, Sophie Scamps. That is, Briggs had a ready-made solution at hand. It was, however, a step too far for her, so her report has flopped allowing the government to keep “jobs for mates” alive.

The chance to knock off these insidious habits is unlikely to come around again for a very long time. That’s a shame.