Bill Gates knows the climate and poverty facts but misses the politics

December 7, 2025

Bill Gates downplays climate catastrophe, wolves are blamed – or credited – for ecosystem repair, and China’s energy surge defies Western narratives.

Bill Gates’s “tough truths about climate”

Bill Gates has dismissed the “doomsday view of climate change” on the basis that although some people, particularly people in poor countries, will suffer serious consequences, it will not lead to humanity’s demise and most people will be able to live and thrive for the foreseeable future.

Gates suggests that too much attention is focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the short term and this is diverting resources away from more effective ways of improving life as the world warms. He wants more emphasis on tackling under-development, poverty and disease in poor countries where about eight million people per year are killed by poverty-related health problems, an order of magnitude greater than those killed by climate change.

Gates wants the world to focus on evidence-based investments and policies that generate the innovations needed to, for instance, make electricity more widely available, cheaper and cleaner (eg. improve wind power, install highly efficient power lines and develop nuclear fission and fusion technologies), and create more productive farms with lower methane emissions. Improvements in agriculture are at the top of Gates’s list of best buys.

Gates aims to shift resources from climate mitigation to climate adaptation: “we should deal with disease and extreme weather in proportion to the suffering they cause and go after the underlying conditions that leave people vulnerable”. The goal is to make everything as cheap to do cleanly as it currently is to do dirtily: “we need more breakthroughs and luckily humans’ ability to invent is better than it has ever been.”

I imagine that if you are Bill Gates you have pretty much unlimited access to information and experts, so I’d be cautious about disagreeing with any of the statistics he presents or anything he says about technology, even if I wanted to – which generally I don’t. Many of us in the health, environment and social policy fields have been making the same arguments about the need for more emphasis on reducing poverty, improving public health and reducing inequalities for decades.

The problems I have with Gates’s arguments are not with what he says but with what he doesn’t:

- We aren’t in an either-or situation – we don’t have the luxury of choosing between improving health and poverty or reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We need to tackle climate change mitigation and adaptation simultaneously with all the other threats to our natural environment, social and economic development, equity and health.

This is not only because it’s the right thing to do but also because they are interconnected and we can’t solve one without solving the others. And for those who say, “we can’t afford to do everything at once”, a) we can’t afford not to – we haven’t got any other viable option, and b) we can stop wasting money on activities that do nothing to promote a better life for the vast majority of the global population.

- Even if Gates is broadly correct in dismissing the doomsday view (but for an alternative perspective, see 600 scientists and Julian Cribb), he seems to ignore the fact that some communities face a serious existential threat to their existence in the near future from, for instance, rising sea levels, thawing permafrost, melting glaciers and extreme heat. Try telling them that their all too justifiable “doomsday” concerns are unwarranted.

- While Gates (rightly) prioritises agriculture, the problem is not simply making it more efficient and cleaner. The most catastrophic possibility is the collapse of our terrestrial and marine food systems. Gates doesn’t say anything about the already declining yields from land and sea caused by a range of environmental insults – rising temperatures, desertification, droughts, loss of topsoil, decreasing numbers of insect pollinators (possibly the most likely cause of a near-term precipitous drop in crop yields), overfishing, eutrophication, to name a few.

- Gates has nothing to say about greed, privilege, organised resistance to change by vested interests operating at local and global levels, exploitation, within-country and international geopolitical tensions, imperialism, colonialism, or the capital sunk in still-functional but no longer needed assets. He’s ignoring the five Ps that will get in the way of his grand scheme, personalities, privilege, power, political economy and politics.

- Gates seems to think that if we better utilise investment, research, innovation and market mechanisms, Adam Smith’s invisible hand will magically deliver green capitalism and capitalism-with-a-human-face and all our problems will be solved. Unfortunately this ignores the sine qua non of capitalism – the need for ever increasing profits and capital accumulation. The development of global monopoly capitalism (a concept with which Microsoft has some familiarity) has further strengthened corporate power and resistance to any change that threatens their profits. It seems highly risky (and unlikely) to me to expect the system that created our current crises to solve them.

So, Bill, ‘High Distinctions’ for reminding everyone of the urgent need to attend to the very pressing problems of the less privileged around the world and for suggestions regarding the technologies to improve adaptation. Sorry, though, ‘Fails’ for promoting the idea that it’s climate mitigation or tackling the pressing problems of poor people and for your faith in the market and capitalism (even though you never use the word) as the routes to salvation.

Do reintroduced large predators restore landscapes and ecosystems?

It’s one of the great ecosystem recovery stories. After grey wolves were hunted to near-extinction in the US in the early 20th century, elk and other grazers had a field day. They increased in numbers and were able to feed freely in riparian zones. Grasses rather than trees increased in the river valleys and the waters flowed more quickly. The ecologies of the land and waterways changed radically.

Following the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park in the mid-90s, elk grazed less safely, willow and aspen regenerated on the river banks and beavers were able to return, build dams and slow the water flow. Hey presto, ecosystem restored. That’s an oversimplification but you get the idea and can probably see why the wolf program was hailed as a great success for the idea of reintroducing top-predators to landscapes and restoring the status quo ante. But is it correct? Subsequent research has produced varied findings.

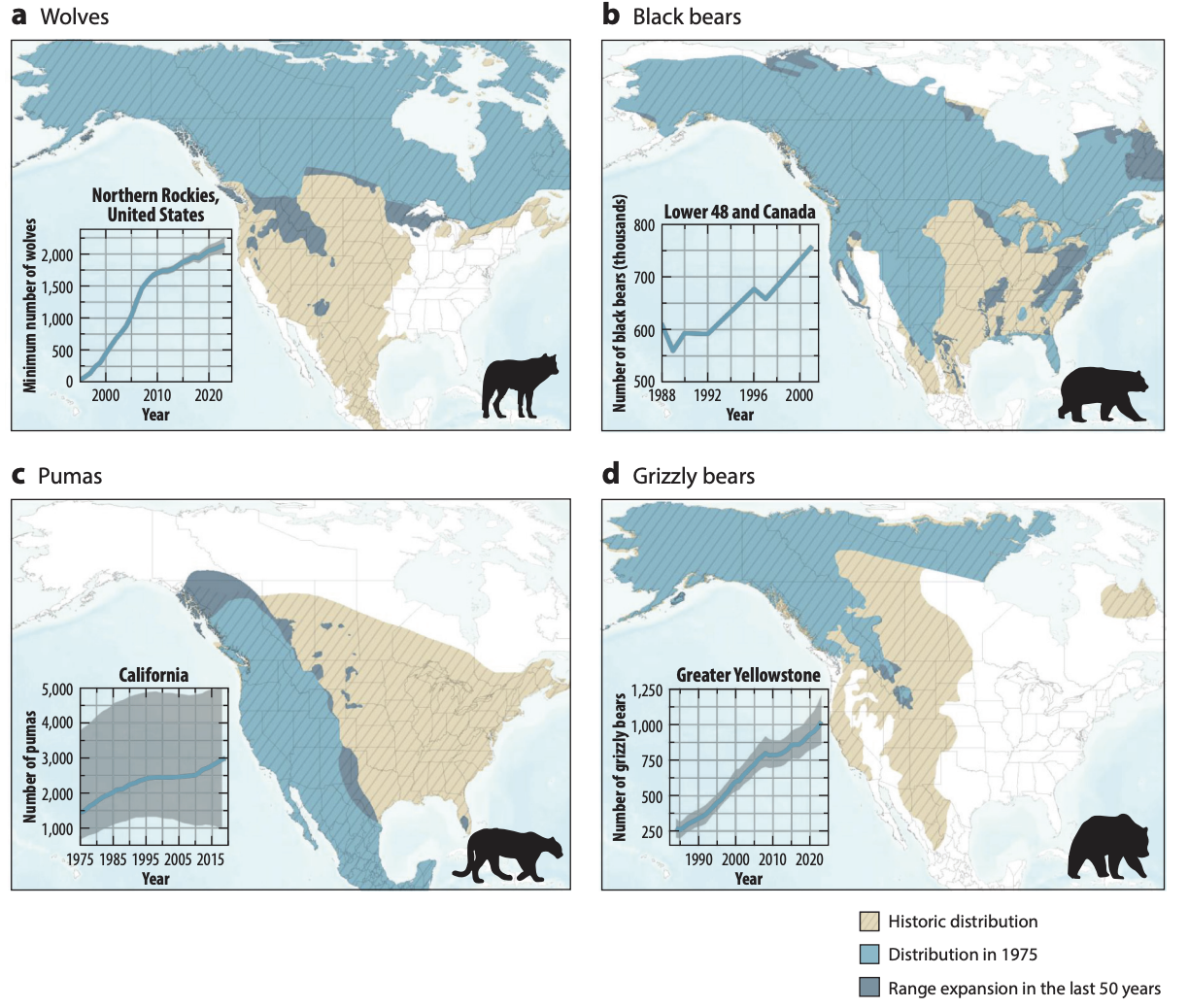

Examples of changing numbers and distribution patterns of predators in North America over recent decades.

So, can the restoration of large predators repair damaged ecosystems (and if so, exactly how) or are some changes beyond reversal? An analysis of 170 publications since the 1930s has shown, not surprisingly, that the presence of wolves alone may not be enough to restore landscapes and ecosystems. Rather, the findings suggest “that while large-carnivore recovery in Yellowstone has triggered some ecological changes consistent with trophic cascades, complex interactions involving competition, climate, other herbivores, and human influence obscure a clear causal link between predator return and widespread vegetation recovery”.

The paper’s lead author commented “In most mainland systems, it’s only when you combine wolves with grizzly bears and you take away human hunting as a substantial component that you see them suppressing prey numbers. Outside of that, they’re mostly background noise against how humans are managing their prey populations. You’d be better off avoiding the loss of beavers and wolves in the first place than you would be accepting that loss and trying to restore them later.” Having some evidence to back up common-sense is always nice, isn’t it.

When do migrants become English?

This is a cheap shot, I know, but the quotation below is quite amusing.

“English is the dominant language in research – it’s essentially the lingua franca of science” (from ‘The Climate and Biodiversity Knowledge We Lose When Everything’s in English’)

On the other hand, maybe the joke is on me. Lingua franca, just like bungalow (Hindustani), kindergarten (German), tsunami (Japanese) and billabong, now seems to be standard English. All five are long-standing entries in the OED.

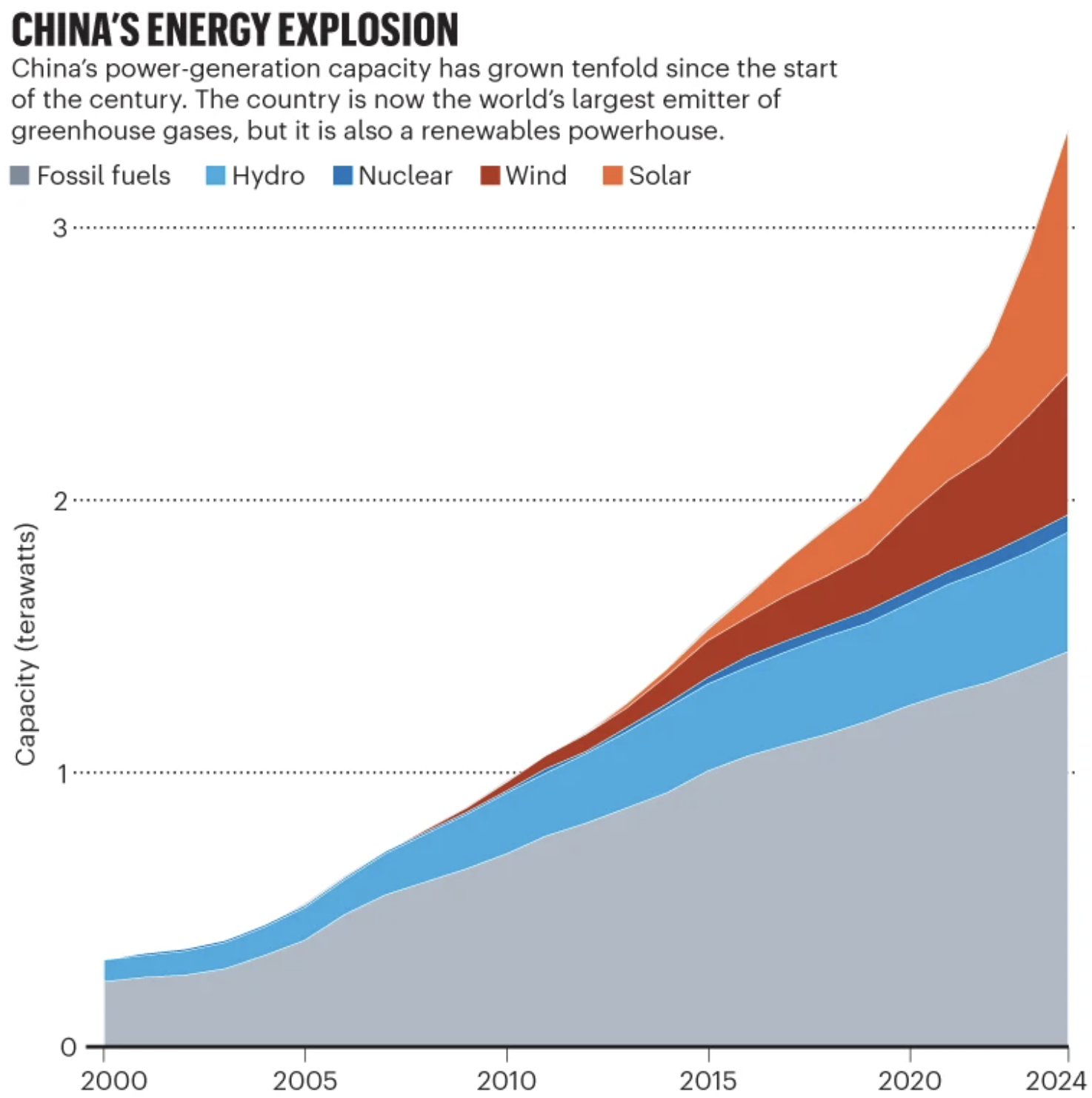

China’s energy explosion in a nutshell

- Since 2000, China’s energy generation capacity has grown ten-fold.

- China is still building the vast majority of the world’s new coal-fired power stations, although many of their new plants are operating well below capacity and/or are seen as back up.

- China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and has driven 90 per cent of the global growth in CO2 emissions since 2015 but it has only half the emissions per person as the US.

- China’s fossil fuel generated emissions seem to have peaked.

- President Xi Jinping recently announced plans to reduce GHG emissions by 7-10 per cent from peak levels by 2035.

- China is also the world leader in the generation of renewable energy and the production of equipment needed for the transition to a decarbonised economy.

- China is the world’s leading refiner of 19 of 20 strategic minerals required for the energy transition, AI chips, data centres, high tech applications, industry and defence. For 13 of these it refines over 60 per cent of the global supply and for six it is over 80 per cent. More than half of the 19 are subject to export controls.

Michael and the spider

If you like a feel-good movie, here is 10 minutes of absolute joy on so many levels.