Environment: More good recycling is needed – emphasis on good

December 21, 2025

Low levels of plastic recycling are bad for human health and the environment. For lead, high levels of dangerous recycling are doing the damage. Northern Australia’s vast, ecologically relatively intact savannas are undervalued.

Plastics harming the health of humans and the environment

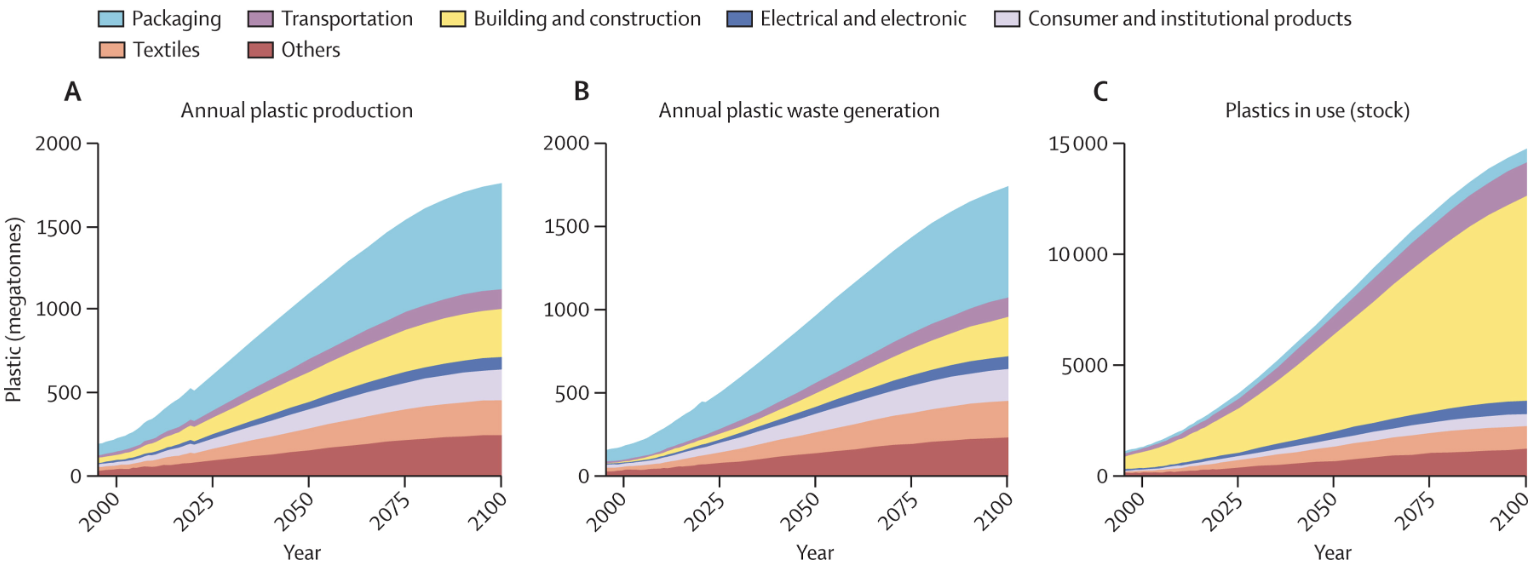

The production of plastics has increased from 2 megatons (Mt) per year in 1950 to 475 in 2022, with a projection of 1200 Mt by 2060. It almost goes without saying that China is the biggest producer, responsible for over 40 per cent of the annual global total.

There is now 8,000 Mt of plastic waste polluting the planet from the depths of the oceans to the tops of mountain ranges. Less than 10 per cent of plastic is recycled. Three factors are principally responsible for the worsening plastic pollution crisis: global plastic production is increasing; recycling is failing; plastics fragment into ever smaller particles, most of which do not biodegrade in the environment. A 70 per cent reduction in the production of single use plastics would avoid the consumption of almost four million barrels of oil per day (a staggering 5 per cent of total daily consumption) and cost the petrochemical industry US$138 billion per year.

Image suppliedMaking matters worse, plastic pollution and climate change, which have common origins in hyper-consumptive societies, should be viewed as joint crises. Climate change is contributing to the durability, abundance, wide distribution, exposure to and impacts of plastic and its associated chemicals in our marine and fresh waters, soils, atmosphere, animals and plants. Together, climate change and plastic pollution can have significant synergistic (not just additive) ecological effects. Large, long-lived aquatic organisms at the top of food webs (apex predators) seem to be particularly vulnerable and human agricultural and fisheries systems are not immune.

Following the Paris Agreement in 2015, The Lancet medical journal conducted an authoritative, systematic review of the effects of climate change on health. They followed this by establishing an international research collaboration to create a health-focused, global monitoring system to track progress ( _Lancet Countdown_ series on health and climate change). The Lancet has repeated the process to publish the first Countdown on health and plastics.

All stages of the life cycle of plastics – the production process, the chemicals used, the microplastic and nanoplastic particles (MNPs) generated both intentionally and when plastics breakdown, and plastic waste – have proven or potential, direct and indirect harmful effects on most if not all human cells and body systems leading to multiple diseases and premature death. Production workers and waste pickers are at high risk of injuries and exposure to toxic chemicals, as are adjacent communities. For example:

- While the majority of the over 16,000 chemicals that may be incorporated in plastics have never been tested for toxicity, more than a quarter are known to be hazardous to human health. They have multiple health effects across all ages but infants in the womb and young children are particularly at risk of, for instance, miscarriage, reduced birthweight, congenital malformations and reduced cognitive function.

- Plastic debris and MNPs in the environment create habitats that support the growth of microorganisms and interactions among them which can drive the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Plastisphere, a portmanteau word developed about a decade ago, describes the ecosystems of microbial communities that live on plastic waste.

The Lancet produced the Countdown to inform discussions at this year’s conference to finalise the development a Global Plastics Treaty. Unfortunately, the negotiations collapsed in the face of fierce opposition from several major oil and gas producing countries and companies.

Northern Australia’s valuable tropical savannas

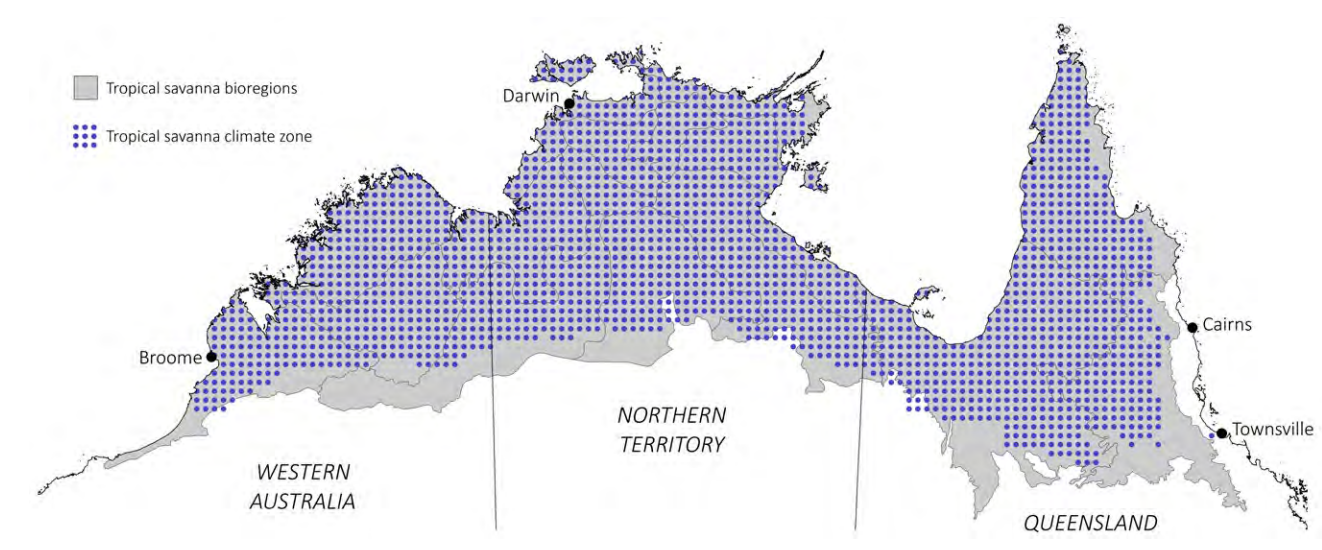

Tropical savannas cover 20 per cent of Earth’s land surface. They contain great ecological diversity and are characterised by an open tree canopy above an understorey dominated by grasses and sparse shrub cover. Patches of other ecosystems such as rivers, wetlands, rainforests (in areas with higher rainfall) and heathlands are scattered across the savannas.

The savanna’s structure is maintained by a strong wet-dry annual cycle: high wet season rainfall that leads to the accumulation of grass biomass followed by an intense dry season that dries the grass and facilitates fires (and did so long before humans appeared on the scene). The grasses, fires and seasonal droughts inhibit the growth of trees.

Globally, the largest continuous savanna regions occur in South America, Africa and Australia but Australia’s are the most ecologically intact. The savannas of northern Australia cover 1.33 million square kilometres (about the size of the NT), extending over 2,500 km from the Kimberley to almost the coast of Queensland. As well as their biological richness, Australia’s savannas have considerable cultural and spiritual significance for Aboriginal populations.

Notwithstanding the relatively intact nature of Australia’s savannas, they have suffered from – you guessed it – land clearing, invasive species such as cats and Buffel Grass, introduced herbivores and agriculture, mining and climate change. Removal of the traditional owners since 1788 has led to altered fire management practices and more frequent high-intensity fires. Consequently there have been dramatic decreases in populations of native flora and fauna (mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates) and many are now threatened with extinction even in National Parks.

Recommendations by the Northern Territory’s Environment Centre (ECNT) for better policy and management practices to protect the NT’s savannas include:

- Better NT environmental and land use laws, including a Biodiversity Conservation Act, and integration of climate change considerations into environmental and land use policies and laws.

- Stricter limits on land clearing and improved oversight and regulation of habitat destruction.

- Regular state of the environment monitoring and reporting and development of a biodiversity strategy.

- Enhanced protection of critical ecosystems, habitats and biodiversity hotspots.

- Encouragement of sustainable agriculture and horticulture.

- Integration of environmental and cultural concerns and their management, including supporting Indigenous land management.

- Increased collaboration with local communities and environmental organisations.

- More funding for conservation projects.

Recycling lead batteries sounds like a good idea

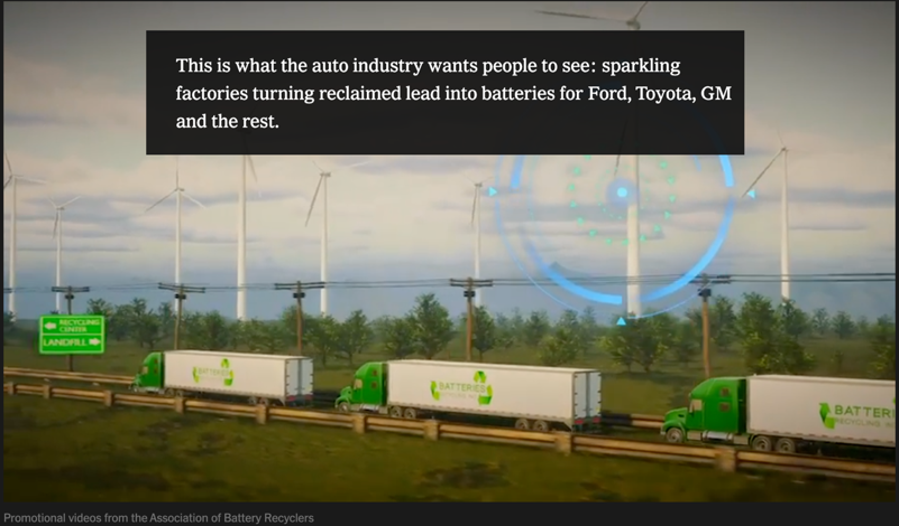

So it’s not surprising that the US auto industry likes to portray lead recycling as the sensible, clean, green, US-based, circular economy alternative to sending old batteries to landfill and mining more lead for the next batch of batteries.

But the reality is often very different:

To reduce the cost of car batteries, US manufacturers started using lead recycled from old batteries. It seemed like a good idea but as the US tightened regulations on lead processing for health reasons, it became increasingly difficult to find locally recycled lead. The industry started sourcing it from overseas where expenses are lower, workers are desperate for jobs and occupational health and safety regulations are often less restrictive. Plus, governments are keen to generate jobs and foreign investment. Ten years ago, the US imported almost no recycled lead from Nigeria. Now, each year the US is sending tens of thousands of second-hand cars to Nigeria and taking back over 34,000 tons of lead, enough to make millions of batteries.

Battery recycling facilities emit vast quantities of lead-contaminated exhaust that pollutes the air, land, water supplies, crops, sports fields, everything in the vicinity. Lead is extremely harmful to human health, causing damage to, for example, the brain, nervous system, liver, kidneys and eyes and impairing children’s intellectual development. No level of lead in the body is safe. Globally, lead poisoning causes more deaths than malaria and HIV combined.

Ogijo, Nigeria, is the location of at least seven battery recycling facilities. People living near or working in the factories volunteered to have their blood sampled. Among those tested, all 16 workers, 41 of 56 adults and 8 of 14 children had dangerously high levels of lead in their blood. Dust and soil samples showed lead levels almost 200 times the hazardous level.

The supply chain from a battery recycling facility in Africa to a new battery in the US involves many intermediary stages and handlers. Safety standards and adherence to regulations (where they exist) vary greatly and there’s a tendency for each company to claim that while they behave responsibly and adhere to the relevant regulations they can’t be held responsible for others in the industry and must rely on their suppliers’ assurances that they are doing everything properly. Similarly, it’s easy for governments to pass the responsibility for developing regulations and monitoring adherence to other jurisdictions.

Lead batteries can be recycled cleanly but it’s expensive and the current recycling chain facilitates cheap alternatives. According to the New York Times, “The industry, in effect, built a global supply system in which everyone involved can say someone else is responsible for oversight”. A regrettably common tale, I fear.

Confused by carbon offsets?

Are you completely bemused by the language and science of carbon emissions and their offsets: carbon credits, junk credits, ACCUs, fossil fuel phase-outs, hard-to-abate industries, net and real zero targets, carbon neutrality, price of carbon, the social cost of carbon, negative externalities, permanency, integrity, transparency, paying to pollute, Safeguard Mechanism? If so, you’re not alone.

Well, Millie Muroi has written the article for you. She doesn’t specifically use all these terms but she does discuss the concepts in easy to understand language. Her conclusion is summed up in her article’s title: “Coalition is no friend of environment – neither are carbon emissions offsets”.

If you’ve read Ms Muroi and would like a little more detail, The Australia Institute’s factsheet is helpful. It is also the source of David Pope’s cartoon.

Forests, how lucky are we!

I’m sure I don’t need to tell P&I readers about the benefits conferred by forests, not only trees on land but also mangroves on the shoreline. Nonetheless, the graphic below is a nice reminder of the manifold ways in which humans benefit from them.

Sadly, Christmas trees are missing from the pictures above but I wish you all a very happy whatever-it-is you celebrate at this time of year. See you again on 25 January.