Friends and frenemies: Australia’s China policy is stuck in a four-tier mindset

December 8, 2025

Australia’s stabilisation of relations with China is welcome, but the old adversarial mindset remains intact. Institutional biases, selective outrage and context-free media narratives still shape how Australia sees China, limiting any genuine foreign policy reset.

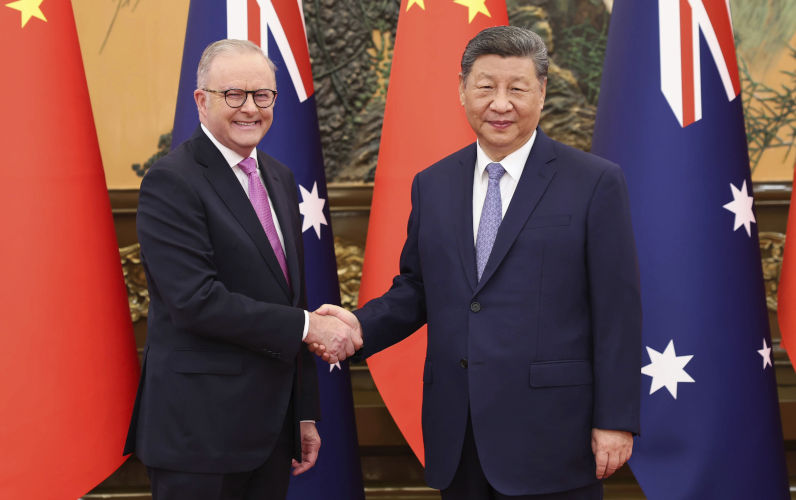

Recent analyses highlight a persistent and dangerous tension at the heart of Australian foreign policy. While the Albanese government has been praised for stabilising the tumultuous relationship with China, a series of critical articles suggests this “reset” may be more rhetorical than substantive.

The authors argue that a deep-seated, adversarial framework – sustained by institutional biases, hostile media narratives, and a dangerous form of historical amnesia – continues to shape Australia’s approach to its most significant trading partner, preventing a truly pragmatic and interest-driven engagement.

The hidden structure of Australian foreign policy

Australia’s foreign policy is guided by an unspoken, but implicit, four-tier system that shapes how we react to different countries’, this framework influences Australia’s diplomacy, trade, and strategic partnerships – often contradicting its stated commitment to universal values and international law.

This four-tier system highlights tensions in Australia’s strategic culture: between idealism and pragmatism; alliance loyalty and national independence; moral consistency and strategic flexibility. These tensions have grown as Australia navigates the complex great power competition in the Asia-Pacific.

The system’s effects go beyond bilateral ties, impacting Australia’s credibility as a middle power, its role in multilateral forums, and its ability to pursue policies serving Australian interests. Selective moral standards have weakened Australia’s soft power and reduced its influence just when regional leadership opportunities arose.

Understanding this system is key to explaining the sharp deterioration in Australia-China relations from 2016 to 2022, and why the Albanese Labor government’s efforts to restore functional ties suggest that there may be a fundamental shift in Australia’s international approach.

The four-tier categorisation system

- Allies - we take our strategic directions from these and never criticise whatever the issue (coincidentally, these are white Anglo-Saxon countries). To these we provide unconditional support.

- Friends, those we chat to privately if there is an issue, but never attack publicly and generally support.

- Neutral, those we don’t care about, and

- Enemies – those we use any reason (justified or not) to attack.

We choose our outrage based on who we wish to demonise – not the act itself. Australia’s foreign policy inconsistencies can be understood when viewed through this framework.

During the 2016-2022 period, China was firmly relegated to Tier 4, a shift with disastrous consequences for Australian trade and diplomacy. The current Labor government has commendably attempted to move China back towards Tier 3. However, as Ronald C Keith argues, the language of the government’s “new regional architecture” is still laden with the assumptions of the old adversarial posture.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s rhetoric of “balance” is viewed with suspicion in Beijing, which, as Keith notes, questions whether it has ever been treated with the equality Australia now espouses. The continued reliance on the United States as the ultimate “keeper of balance” implicitly casts China as the power to be balanced against, perpetuating the Tier 4 dynamic.

Information warfare: from pulp geopolitics to historical amnesia

This Tier 4 mentality is sustained by powerful institutional forces, most notably the security agencies and a compliant, often hostile, media. This information warfare operates on two levels: the overt creation of fear and the covert erasure of context.

First, as detailed by John Queripel and Fred Zhang, is the practice of “pulp geopolitics”. Queripel describes the “security panic” manufactured around a senior Chinese official’s visit, while Zhang systematically deconstructs how News Corp’s editorial reflex weaponises routine business and environmental stories into geopolitical dramas. By framing a new EV launch as an “assault” or a corporate supply chain decision as a “surrender,” the media primes the public for conflict, making rational policy debate impossible.

Second, and more insidiously, is the promotion of what Zhang calls a “ dangerous form of historical amnesia”. In a separate analysis, he highlights how Western media outlets uniformly framed China’s furious response to a Japanese official’s security pronouncement as irrational “wolf warrior diplomacy.”

What was systematically erased was the historical context: the official used the term 存立危機事態 (“survival-threatening situation”), a specific legal phrase whose conceptual framework directly echoes the justification Imperial Japan used for its invasion of China and the attack on Pearl Harbor. For China and other nations that suffered under Japanese occupation, this language is not neutral; it is a traumatic reminder of past aggression. As Zhang powerfully argues, omitting this context is akin to ignoring the historical weight of the word “Lebensraum” in a European security discussion. This erasure of history denies China’s legitimate security concerns and recasts them as baseless paranoia, perfectly fitting the Tier 4 adversary narrative.

The folly of subservience

The unquestioning hostility towards Tier 4 adversaries is the logical consequence of Australia’s unconditional loyalty to its Tier 1 ally, the United States. As Mark Beeson, reviewing Clinton Fernandes’ Turbulence, argues, Australian policy planners are motivated by a “single standard – does something protect or advance US power and Australia’s relevance to it?”. This 80-year default setting of subservience has led Australia into “pointless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan” and now into the AUKUS agreement, which Fernandes describes not as a nation-building project, but as a “contribution of people, territory, materials, money, diplomacy and ideology to the war-fighting capabilities of the United States.”

This subservience breeds hypocrisy. Australia is quick to criticise China’s human rights record (a Tier 4 adversary) while remaining silent on the actions of the US or its allies (Tier 1 and its protectorates). As Fernandes concludes, “Human rights will be ignored or highlighted as needed” to stay onside with the US. This selective morality, driven by alliance loyalty, undermines Australia’s credibility and prevents an independent foreign policy based on genuine national interest.

Beyond rhetoric and amnesia

The critiques from these authors reveal a fundamental challenge. A genuine reset in Australia-China relations cannot be achieved through diplomatic rhetoric alone. It requires a conscious effort to dismantle the institutional and ideological structures that perpetuate the Tier 4 adversarial mindset and the Tier 1 subservience that underpins it.

This means questioning the narratives of security agencies and, crucially, demanding more from our media. A public sphere saturated with pulp geopolitics and historical amnesia cannot sustain an informed debate about the national interest. As Keith points out, China has for decades promoted principles of “peaceful coexistence”. A truly pragmatic Australian foreign policy would explore these avenues for cooperation with intellectual honesty, rather than reflexively treating them with suspicion.

The Albanese government has taken a crucial first step in stabilising the relationship. The next, more difficult step is to move beyond the old assumptions and the hostile, context-stripped headlines. It requires building a relationship based on mutual interest and a clear-eyed understanding of history, not fear. Only then can Australia escape the self-imposed constraints of its own rigid and outdated foreign policy framework.