‘This will be my dream project’: How we got Frank Gehry to design the UTS ‘paper bag’

December 9, 2025

“I’m up for it” was the response of arguably the most famous architect in the world to our hesitant inquiry. “This will be my dream project,” he said.

With the announcement of Frank Gehry’s death at age 96, it seems almost unreal to recall his fleeting presence in our city. But his legacy is with us in brick, glass and steel in the visible form of the UTS Business School at the University of Technology Sydney, more popularly known as “the paper bag building”.

I had just been appointed dean in 2009, doing what most deans do at the start of their term – engaging with staff, students and partners on a new vision and strategy for a very practical mainstream faculty of business. We were assisted in this by a design thinking group, Second Road.

We wanted to be ahead of the game, preparing students not just for existing jobs but for the jobs and opportunities of the future. In addition to specialised discipline knowledge, these would require “boundary-crossing” skills of creative and analytical problem-solving and entrepreneurial thinking.

As the faculty had outgrown its accommodation, we secured the support of the university to design and construct a new building on the site of the old Dairy Farmers warehouse in Ultimo. But not just any new building, let alone yet another utilitarian box. It had to reflect our vision for business education.

The obvious candidate was Frank Gehry, but how would we reach him? As it happened, one of the Second Road consultants knew him from a past life. She called him and shared our plans. “Are they serious?” Frank asked. “Get the dean to send his strategy.”

Frank was hooked. He was jaded by the narrow interest in the flamboyant visuals of his buildings at the expense of the design philosophy behind them. But in UTS he found a client who shared his uplifting, transformative vision of education. And within weeks he was in Sydney to check us out.

We started with a harbour cruise to show off the skyline, accompanied by fellow Pritzker prize-winner Glenn Murcutt and Penny Seidler. “It’s bland,” said Frank, referring to the skyline. “We can do better”. Next day he asked us, as he always did in a new assignment, to “show me the buildings you love”.

Apart from the Opera House (of course) and some of the Seidler buildings, what was there to show among Sydney’s mediocre examples of modernism? At least at that time, it was as though we didn’t have to try, given the spectacular beauty of our harbour backdrop.

I plumped for Richard Johnston’s striking towers and Renzo Piano’s Aurora Place, with its translucent sails seemingly riffing the harbour. “That’s the same one Renzo did in Berlin”, said Frank. “I never do the same building twice.”

We were beginning to discover what made Frank tick. It wasn’t our efforts at emulating the international style, but the sandstone origin story around Macquarie Street and Martin Place. “Sydney’s soul lies in its fabric of urban brick.”

Frank already had a feel for the city as he visited previously in 1979 to inspect the Opera House and present a lecture at the then-NSW Institute of Technology’s neo-brutalist tower, later to become UTS. Now he was back to undertake his first and only project in the southern hemisphere.

Frank’s unique approach was to start, not with external appearances, but to “design from the inside out” in dialogue with the users about the functionality of the internal spaces. He asked the faculty: “How do you want to work with each other, with students and the community?”

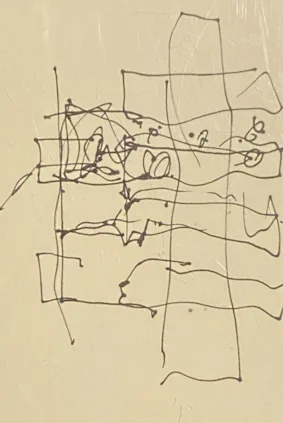

Much of Frank’s approach involved sketches and block models, as well as design software. He saw the design process as “liquid until we allow it to crystallise”. His sketch for our building imagined it as a “treehouse” with a trunk of social spaces branching into areas of collaborative research and teaching.

He texted: “It’s a gnarly project, a business school, not sexy like a museum or concert hall. We love the prospect. Thinking of it as a treehouse came tripping out of my head on the spur of the moment in your presence and was not contrived. But on reflection the metaphor may be apt. A growing, learning organism with many branches of thought, some robust and some ephemeral and delicate.”

This approach is often misunderstood as being somehow flippant and not sufficiently rigorous. I had to push back on such comments at the opening of the building 10 years ago. This is a building that was finished on time, on budget, as well as being an inspiration for Sydney’s architecture and generations of students to come.