Environment: It’s official - Australia’s extreme weather events will get more severe

January 25, 2026

Australia’s first Climate Risk Assessment confirms we’re in for more frequent and more extreme climate hazards. Ten years on from the Paris Agreement, Australia and governments around the world are still kicking the climate action can down the road.

Australia’s climate risk assessment

The government published Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment in September 2025. While it is eminently readable, it is far too long and detailed for me to summarise so I’ll limit myself to highlighting a couple of features.

Australia is likely to experience more frequent and more extreme climate hazards, with an increase in concurrent and cascading climate emergencies, often in new locations and at new times of year. Historical patterns of extreme weather events will be poor indicators of future risk. Extreme weather will create severe problems across Australia with some communities (e.g. disadvantaged households, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, very young and very old people, people with existing health problems and outdoor workers) being most vulnerable.

States and territories will be exposed to different risks and impacts:

Heatwaves (brown thermometer in the map) will be more common across northern Australia and vector-borne diseases such as malaria (blue virus) in the southern mainland states. Sea level rise (grey arrows) will be greater along the east coast, crop yields (green tractor) lower in the southern mainland states, and loss of coral reefs and marine biodiversity (orange coral) greater in Queensland and WA. Damage to ecosystems (light green leaves) and disruptions to supply chains (purple A-B) will be widespread.

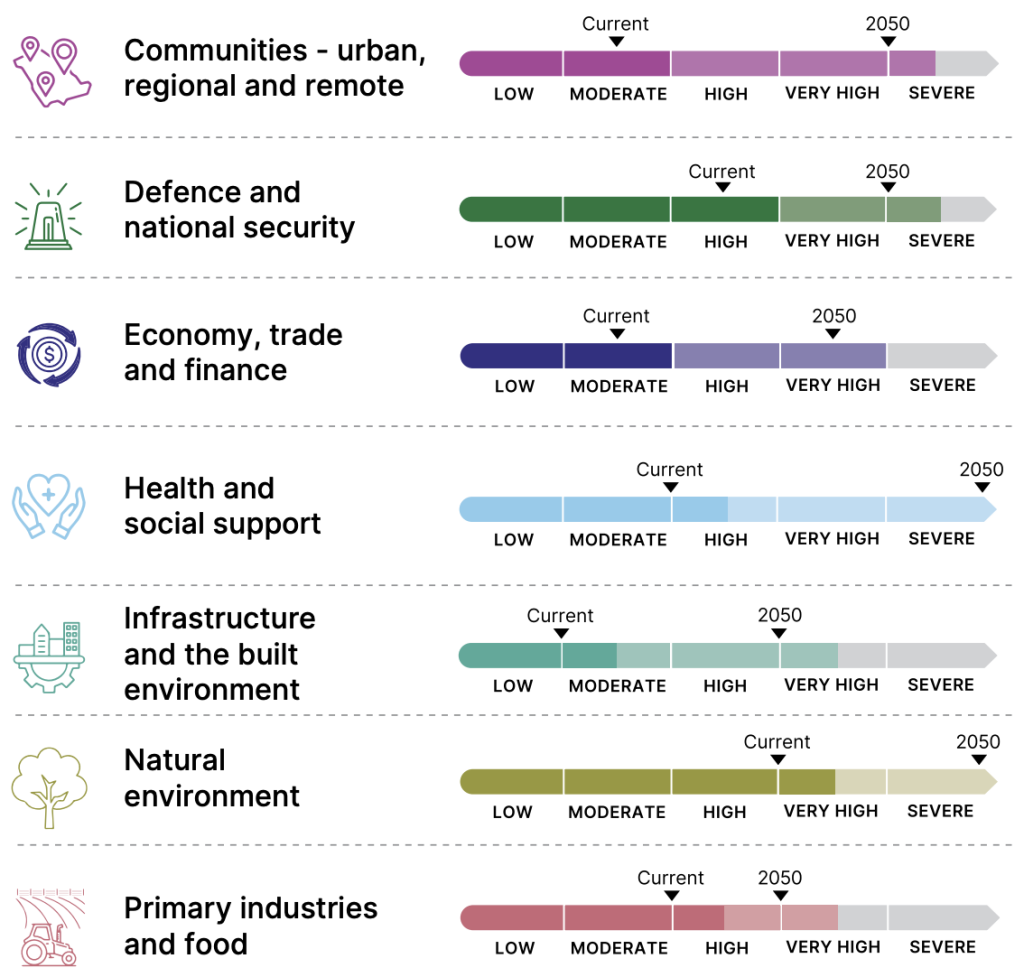

Between now and 2050, climate related risks increase for all of Australia’s natural and social systems, with the natural environment and health and social support reaching the most severe level.

For clarity, the National Climate Risk Assessment is not the same as the assessment of climate risks external to Australia that was completed by the Office of National Intelligence in 2022 and has still not been released by the government. It’s possible that the government thinks that, to corrupt Jack Nicholson’s line, the public can’t handle the truth. It’s more likely though that the government doesn’t want the public to know that the government itself doesn’t know how to handle the truth.

My climate risk assessment is that the principal risk to Australians is that current and future Australian governments will continue the decades-long government policies of refusing to be open and honest with the people about the climate risks and refusing to do what is necessary to minimise them.

What have the French ever done for us?

Or with less of a nod to Monty Python, has the 2015 Paris Agreement done anything to improve life for future generations?

First the good news:

- Climate change is now widely recognised as a global crisis and shared challenge.

- There are internationally accepted targets for keeping warming below 1.5/2.0oC and reaching net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, and a box of tools that promote ambition, commitments, accountability and monitoring.

- Many businesses and regional and local governments have taken a lead in decarbonising their activities.

- Policies developed since 2015 have reduced the projected global warming in 2100 from 3.5oC to 2.7o Full delivery of all nations’ pledges would reduce it to 1.9oC.

- The lower temperature projections for 2100 will (if they eventuate) reduce the risks to human health and wellbeing associated with extreme weather events, sea level rise, biodiversity loss and passing irreversible Earth System tipping points.

- The need for climate justice is recognised and a financial system for helping low income countries deal with existing climate-related loss and damage has been established.

- By 2023, global climate finance from public and private sources had more than trebled and investments in clean technology now exceed investments in fossil fuels.

Now the bad:

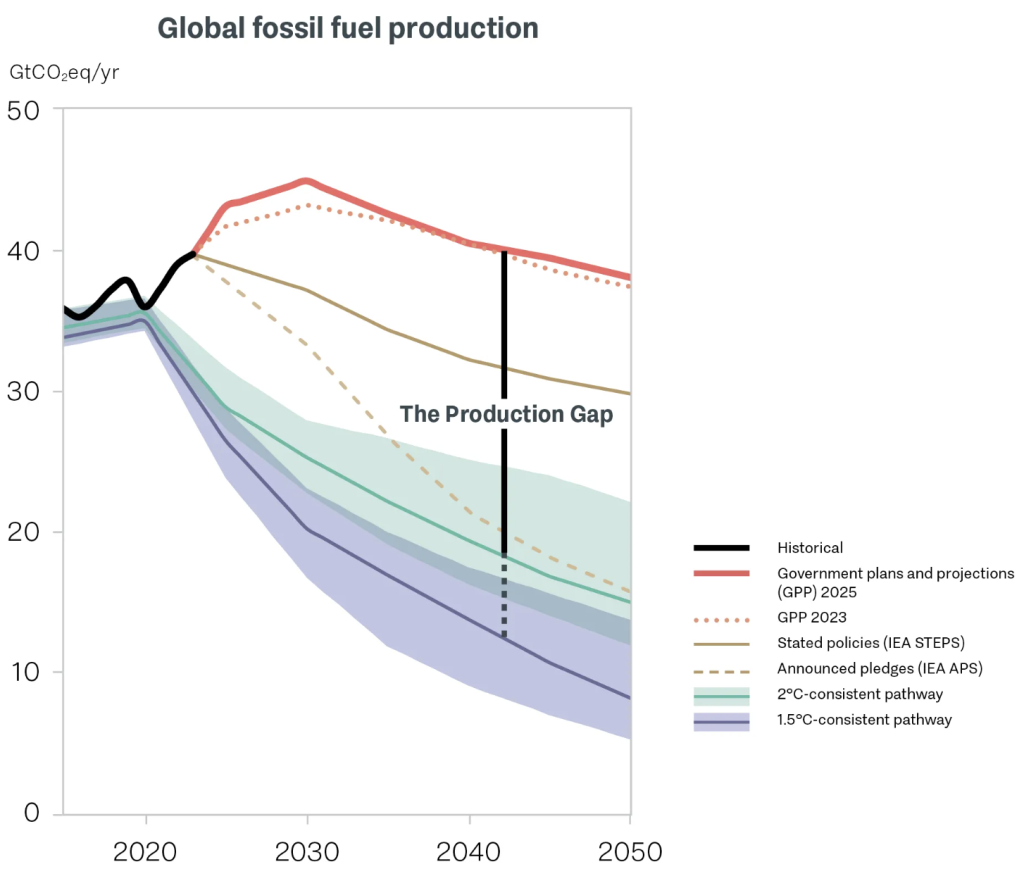

- Fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions have still not peaked globally.

- Fossil fuel-producing countries (and companies) continue to fight against policies to limit the production of coal, oil and gas. Collectively, they are planning to increase production over the next ten years and are currently planning to produce more fossil fuels between now and 2050 than they were planning in 2023. Extraction plans to 2030 are more than double the level consistent with keeping warming under 1.5oC and 77% higher than is consistent with 2.0o

- We are now more aware of the dramatic increase in risks for humans (including our economies) and the environment if warming reaches 2.0oC rather 1.5o Warming of 2.7oC will have disastrous consequences.

- A temporary overshoot of 1.5oC is now inevitable. Overshooting 2.0oC looks likely.

- Warming of 1.5oC risks triggering several tipping points (e.g. loss of warm water corals, irreversibly melting polar ice sheets and permafrost, conversion of the Amazon to a source of CO2 emissions) and setting off tipping cascades.

- Even where change is heading in the right direction, the pace of change is nowhere near fast enough.

- A lack of political leadership has led to collective ambition not matching the Paris Agreement’s aims. There has been insufficient short-term action since 2015 and climate action has flatlined in the last few years.

- The more fossil fuel infrastructure we build now and the more coal, oil and gas we produce, the more difficult and costly it will be to make reductions later.

Climate Analytics concludes that: “The first decade of the Paris Agreement has triggered a structural shift in how the world organises to limit warming to 1.5oC. The gains are uneven and insufficient – but they are consequential and would almost certainly not have occurred at this scale without Paris. The priority must be to keep peak warming as close as possible to 1.5oC.”

Perhaps the best current course of action for countries that are serious about climate action is to go into cruise mode for the next three years and be ready to hit the accelerator hard when Trump leaves the White House (provided that isn’t too late).

Everything you want to know about the world’s forests

Almost a third of the Earth’s land area is covered by forests, of which 45 per cent is in the tropics. How much do you know about them?

Which continent has the largest forest area (25 per cent of the world’s total)?

Which continent’s land area is 49 per cent forest?

Which five countries contain over half of the world’s forests? (Clue: their first letters are B, C, C, R and U)

If you got five or more correct, you should audition for Hard Quiz but to prepare for your grilling by Tom Gleeson you’d better become familiar with the 150 pages, containing 300 figures and tables, of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025.

Here are a few gobbets that caught my eye:

- While the rate of deforestation has slowed, so has the rate of forest expansion. Over the last decade, the annual net loss has been over four million hectares (half of NSW in total).

- Primary forests constitute just less than a third of all the world’s forests. Europe and the Americas have about 75 per cent of the primary forest.

- Planted forests account for 8 per cent of all forests, of which half is intensively managed plantation forest. In South America, plantation forests (95 per cent of which are introduced species) make up almost 100 per cent of the planted forests.

- Of the total forest biomass, about 45 per cent is in the soil, 45 per cent in the living vegetation above and below ground, and 10 per cent is litter and deadwood.

- In the subtropics, fires are the major disturbance to forests but in temperate and boreal forests insects, disease and severe weather are the major threats.

- 70 per cent of the world’s forests are publicly owned and a quarter are privately owned. Indigenous Peoples and local communities manage 3 per cent of publicly owned forests.

Good luck with Tom.

Car battery recycling update

Just before Christmas I wrote about the severe damage being done to humans and the environment in Nigeria by the recycling of old car batteries that had been shipped from the US to Nigeria so that the lead could be removed and shipped back to the US to make new batteries.

It seems, I stress “seems”, that the investigation and report by the New York Times may have had a beneficial effect. The Nigerian government has shut down some of the battery recycling factories and has begun monitoring the local population for lead poisoning and measuring lead levels in the soil and air. A large battery manufacturer in the US has also said that it has stopped buying lead from Nigeria.

Whether this newfound government and industry interest in the dangers associated with lead will result in sustained improvement in work practices in Nigeria or the US car industry taking responsibility for their supply chains remains to be seen, but this case does demonstrate some value in exposing bad behaviour.

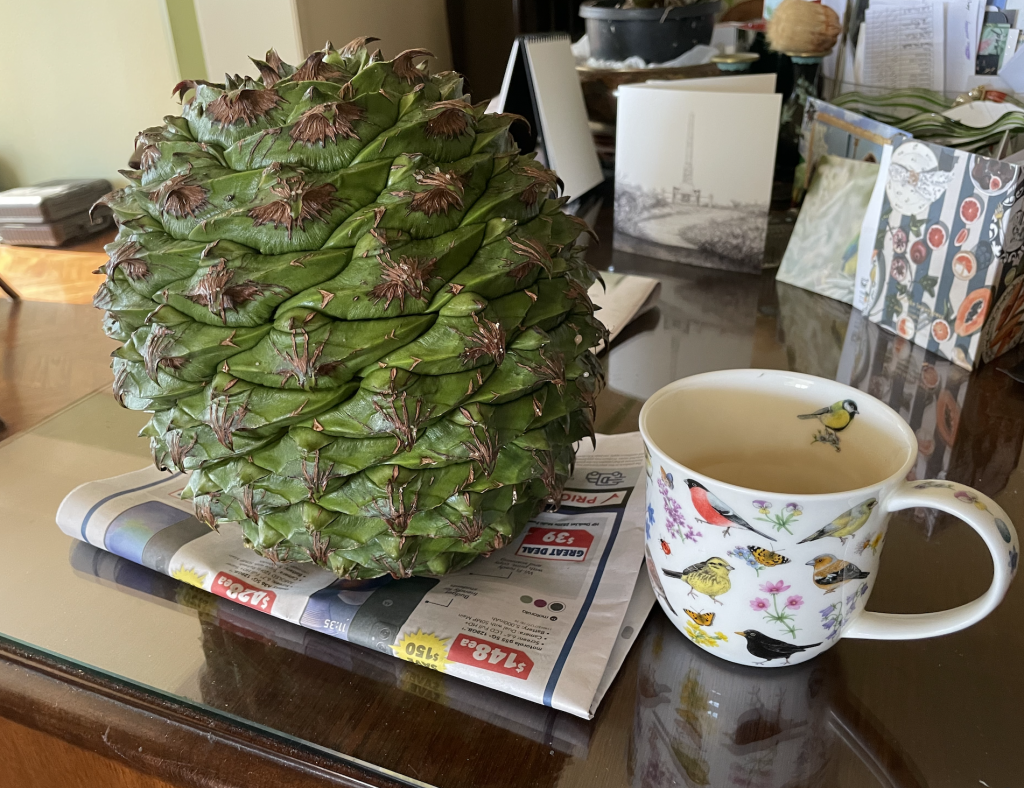

Bunya from heaven

I found the bunya pine cone below a couple of weeks ago on the grass verge of a fairly busy suburban street. The ones I’ve seen previously have sustained some damage from the fall but this one was almost unscathed – perhaps branches had broken its fall and then it had landed on the grass. It weighed 5kg so it would possibly kill you if it landed on your head – the cones can grow up to 10kg.

The bunya pine can live for up to 600 years and is the only surviving species of the genus Araucaria. It is native to Southeast Queensland but will grow elsewhere and many have been planted in public and private gardens. The kernels of each individual segment are eaten by Indigenous Australians and were the basis of bunya festivals.

Bunya pines are magnificent and important for evolutionary, botanical and cultural reasons but my residual public health sensibilities suggest that they are not well-suited to busy public areas.

Photo: Peter Sainsbury