Australia’s economic growth forecasts look upbeat – but the foundations are shaky

January 24, 2026

According to the government the economy is strengthening, but the risks are all on the downside, especially the projection that productivity will grow significantly faster than it has over the previous 15 years.

A few days before Christmas the government released its latest assessment of the economic and fiscal outlook.

Essentially, according to the government, things are looking good.

Growth in total GDP, which was 1.4 per cent in both 2023-24 and 2024-25, is forecast to increase significantly to 2¼ per cent in 2025-26 and 2026-27, followed by 2½ per cent in 2027-28 and 2¾ in 2028-29.

The other good news is that over the year to June 2025, real household disposable income per capita increased by 3¼ per cent, much faster than in any other OECD country and double the OECD average. But over the whole six-year period, since the advent of the Covid pandemic, real household income per capita only increased at an average annual rate of 0.6 per cent.

Also, for many people what is happening to their real wages is a principal determinant of their cost-of-living pressures. But wage growth has been stagnant, with real wages in Australia only increasing at an average annual rate of 0.2 per cent over the 14 years following the Global Financial Crisis, from 2010 to 2024 – an almost imperceptible rate of increase.

In the current financial year, the latest Treasury forecast is that the recent acceleration in inflation will cause real wages to fall by ½ per cent. However, the Treasury expects that fall will then be followed by increases of ½ per cent, 1 per cent and 1¼ per cent in 2026-27, 2027-28 and 2028-29 respectively. In other words, over the next three years we will slowly get back to achieving the normal expected improvement in living standards.

Nevertheless, after years of stagnation, there are some downside risks to these forecasts of even a gradual recovery in Australian living standards, including the highly uncertain global economic outlook, inflation and possible interest rate increases, and lower productivity growth.

Australia is a trading nation, and its economic prospects depend significantly on our trading partners and their demand for our exports.

But in its most recent pronouncement, the government itself thinks that:

“The global economic outlook is highly uncertain and global growth is expected to remain subdued over the forecast period. There are downside risks from global trade disruptions, conflict and geopolitical tensions and more persistent inflation in major advanced economies. Continued uncertainty in trade policy settings is adding to uncertainty and economic fragmentation”.

Inflation is above central bank targets in many advanced economies prompting a tightening of monetary policies, and the shift to a less efficient trading system is creating head winds for the global economy. Generally, consumers are pessimistic – including in the US – and the risk is that labour markets will weaken.

In addition, the world’s two major economies – the US and China – also present particular risks.

In the US, projections for its economic growth have been revised down since Trump took over. For example, in the last year of the Biden Administration, 2024, GDP grew by 2.8 per cent, but in the first year of the Trump Administration, 2025, GDP only grew by 2.0 per cent, and the OECD is only forecasting 1.7 per cent growth in 2026.

Trump’s tariff changes have damaged international confidence in the US economy, as has the very large Budget deficit which has increased to more than 7 per cent of GDP thanks to Trump’s tax cuts, which only help the rich. Furthermore, the US depends heavily upon foreigners to finance that deficit, but on a trade-weighted basis the dollar is now down by about 7 per cent compared to a year ago.

The US stock market is massively over-valued. The price of shares should reflect the present value of their expected earnings in the years ahead, but with a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio that is more than twice as high as its long-term average it must be expected that US share market will face a major downturn. Indeed, the US P/E ratio is now around the level that led to the collapse of the dot-com boom back in 2001, and there could well be a similar collapse in the near future given the extraordinarily high valuations for technology companies relative to their earnings.

Finally, US inflation has accelerated, although the labour market is less tight.

In short, there is a strong chance that the US economy will be widely perceived as being in much worse shape around the time of the Congressional elections at the end of this year.

Turning to China, it continues to rely too heavily on its long-term growth model based on exports and investment. But following the collapse of the property market, because of the over-investment, China has not yet succeeded in developing an alternative growth model which would require much greater private consumption.

So long as this situation continues, Chinese demand will not support growth in other countries, like Australia, as strongly as we have become used to.

Inflation at the end of last year was clearly higher than the authorities had been expecting. Indeed, the Reserve Bank has acknowledged that “Recent data suggest that there is slightly more pressure in the economy than previously assessed”. Its conclusion was that underlying inflation had picked up.

The Reserve Bank now thinks that” the risks of inflation have now tilted to the upside”. The Bank will follow the data, but most market economists no longer expect further interest rate cuts and are programming in at least one or more interest rate increases during this year.

As I have argued previously, it is the cost of servicing a mortgage which has had the biggest impact on living standards, and it seems there is now a significant risk that this will impact again in the year ahead. Furthermore, the recent increase in housing prices has swallowed up all the benefits to new mortgagees from the three interest rate cuts last year.

Productivity growth is the key determinant of real wages and living standards. Unless productivity growth picks up, living standards will continue to stagnate.

The Government’s forecast is that the rate of productivity growth will pick up from a fall of 0.8 per cent last year in 2024-25, to increase by 1.0 per cent in 2025-26, and then by ¾ per cent in each of 2026-27 and 2027-28, followed by 1 per cent in 2028-29.

Interestingly this Treasury forecast for productivity growth is significantly less than its projected growth of potential productivity, which Treasury assumes is increasing at an annual rate of 1.2 per cent. In other words, Treasury believes that the economy will be operating below its potential over the next few years, which should diminish the inflation risks if Treasury is right.

There are, however, good reasons for thinking that Treasury is over-optimistic in its forecasts for both actual and potential productivity growth.

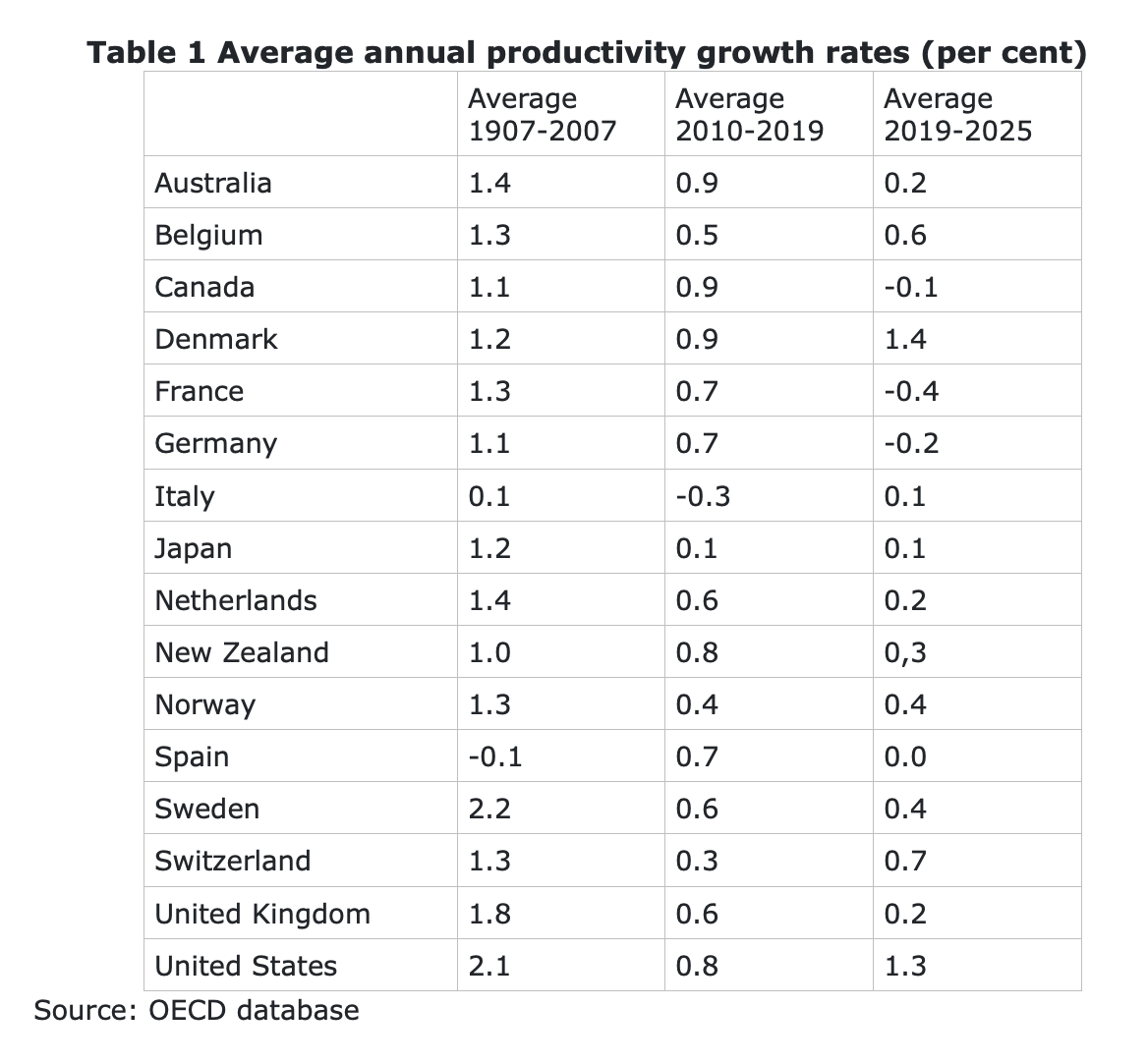

As Table 1 shows productivity growth has been substantially less in all economies similar to Australia’s since the Global Financial Crisis (2007-09) compared to the decade before the GFC (1997-2007). Furthermore, we know that increases in productivity are almost entirely driven by technological change, and as developed economies mostly adopt the same technologies, that is why they all share much the same experience when it comes to productivity growth.

Thus, Treasury’s assumption that potential productivity growth is as high as 1.2 per cent seems much too high. And even the Treasury forecast for actual productivity growth is significantly higher than the OECD forecast for the three-year period 2024-27.

Following its Economic Reform Roundtable last August, the Government is pursuing a number of reforms, including developing a national market with better regulation, improved competition, building a skilled and adaptable workforce, developing a National AI Plan, and taking advantage of Australia’s cheap renewable energy through its plan for a Future Made in Australia.

But while these reforms are worthwhile, they will only improve productivity at the margin.

Productivity growth is the basis for improving living standards. Consequently, it seems likely that living standards will continue to stagnate as experienced for the last 15 years or so.

The implications of this continued stagnation, or at best much slower growth in living standards than most of our life-experience will be further explored in another article to follow soon.