China pushes ahead in 2026 as Trump plays catch-up

February 4, 2026

China entered Donald Trump’s second presidency wary but prepared. Experience has taught Beijing to expect volatility, but also negotiation, shaping a strategy of caution, leverage and long-term planning.

Beijing was well prepared for the return of US President Donald Trump to the White House for his second act. Previous experience showed that Trump would be capricious, but transactional. A deal with China – due to its massive economic size and importance – would appeal to his self-regard. The US abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in January 2026 underlined to Beijing that it is now dealing with a relentlessly self-interested, threatened and defensive United States.

That will make Beijing cautious about avoiding unnecessary escalation, even as it seeks manageable ways to assert what it regards as its legitimate interests in the South China Sea and Taiwan. The major military exercise undertaken near Taiwan in the last days of 2025 demonstrates Beijing’s own relentlessness on this issue.

Over 2025, Chinese reactions to the new US administration underwent various phases.

In response to Trump’s tariffs, China imposed its own. For this, it was rewarded with a US backdown and the implementation of a series of limited deals. The greatest source of leverage was the stoppage of exports of rare minerals sourced and processed in China, on which much high-tech manufacturing in the United States and elsewhere depends. Trump produced copious amounts of bluster on social media, but ultimately returned to the negotiating table. In this way, he looked less like a statesman in control and more like a figure forever playing catch-up.

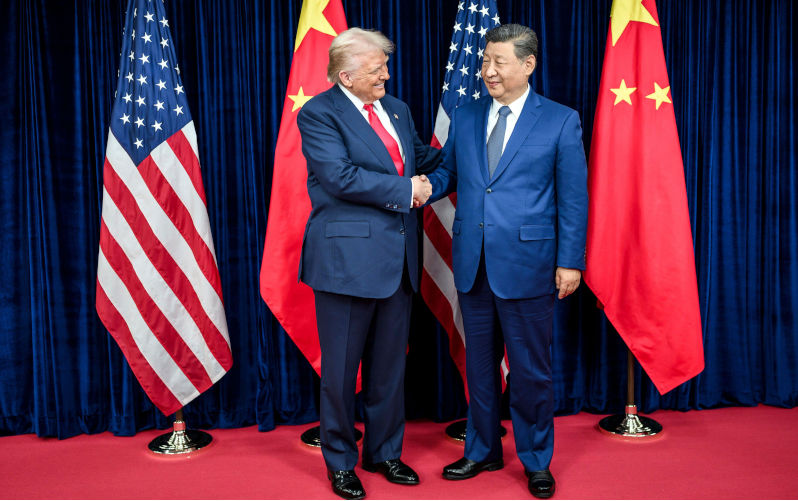

Meanwhile, Beijing pursued side deals with partners like the European Union, reducing tariffs on European pork. Such measures enabled Chinese exporters to deliver a record surplus of US$1 trillion by the end of 2025. When Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping met at the APEC Summit in South Korea in late October, the latter unsurprisingly looked more in control. Standing up to the United States also brought Xi political rewards domestically.

The Chinese economy over 2025 experienced significant turbulence, and this is unlikely to abate much in 2026. The housing market, youth unemployment and weak domestic consumption remain major problems. But with the United States, Beijing senses that it has in Trump a president it can make deals with, and who has silenced the shrill, largely ideologically driven and often overemotional hawks that once dominated the administration.

Chinese self-confidence about its global position was well captured by the nationalistic pride shown during the large military celebrations in Beijing marking the 80th anniversary of the end of the Pacific War. During the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Summit in late August in Tianjin, India’s Narendra Modi, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un all paid homage to a confident looking Xi.

China used Communist Party meetings in late 2025 to set out the expected contours of the year ahead. 2026 is expected to be dominated by the ongoing strife with the United States, accentuated by the implications of the US actions against Venezuela.

But 2026 will also be about the introduction and implementation of the new Five-Year Plan. Socialism with Chinese characteristics no longer depends on the levels of centralised control that characterised the past, even as it sets larger national goals. And while the non-state sector received greater support from the government in 2025 after years in the political wilderness, in 2026 its role will be to contribute to these broader macroeconomic goals even as it continues to seek profit for its owners and workers.

The overall aim will be to realise Chinese technological self-reliance, especially in artificial intelligence, pharmaceuticals and advanced semiconductors (as far as practicable). In the words of the Plenum meeting held in October, the aim is an economy which is ‘innovative and high quality’.

In artificial intelligence, quantum computing, robotics and pharmaceuticals, the country is already starting to breathe down the neck of foreign competitors. China has more STEM graduates than anywhere else on the planet. It has the supply chain infrastructure and industrial base to do things on a scale unlike anywhere else. It is producing research which is increasingly seen as world leading. That is the reality the world will need to deal with in 2026.

While Trump and his allies continue their cultural wars against internal constituencies, Xi is unlikely to let up on the internal purge of military officers, though this is more about countering perennial corruption than heading off direct political threats to the regime.

Speculation will continue about whether the country is gearing up for a massive military onslaught on Taiwan. But while rhetoric and psychological pressure from Beijing won’t abate, hard evidence indicating necessary preparations will be more difficult to come by. No one should forget that if even a modest conflict broke out, the consequences for everyone would be devastating.

In 2026, manoeuvrings and potential events related to the convening of the next major Party Congress in 2027 will begin. The main question is whether any hint of a younger generation of leadership will emerge in significant positions. These will be the potential successors to the Xi era.

While anything overt would be very unlikely, preparing for a China without Xi would appear to be a natural thing for a system that prides itself on planning. Despite this, Xi will remain the dominant political figure in his country in 2026 – and the main global leader who seemingly commands both fear and admiration from his US counterpart.

Republished from East Asia Forum, 2 February 2026