Environment: Small-bodied and short-lived, tiny freshwater fish play big roles in ecosystems

February 8, 2026

A threatened Aussie tiddler flashes a fin for tiny freshwater fish worldwide, toxic PFAS chemicals are all around us and deep inside us and never go away, and illegal gold mining in Congo destroys the environment and communities.

Tiny fishes – miniature marvels that slip through the net

In the global hierarchy of humans’ sentiment for animals, big, visible and dramatic are higher than small and reclusive, vertebrates are higher than invertebrates, warm and fluffy mammals and birds are higher than cold, scaly and slithery reptiles, amphibians and fish, land animals are higher than water-dwellers, and in the water, marine are higher than freshwater. What hope then for enthusing the public about tiny freshwater fishes with unpronounceable names?

SHOAL, a global partnership whose goal is to save 1,000 threatened freshwater fish species from extinction, is trying to invert the traditional hierarchy by telling the exciting stories of ten tiny fishes, none of them longer than 40mm – the last two bits of your little finger. They live in all sorts of places - forest pools no bigger than a puddle, limestone springs, swamps and even fast flowing rivers. But they are enormously important to their ecosystems. They feast on algae, plankton, vegetation and small invertebrates, recycle nutrients, control insect populations and provide food for bigger beasts in the food chain.

Tiny fish have short lifespans and limited ranges in highly specific habitats. They are very sensitive to environmental change - bad news for them but it also makes them useful bioindicators of environmental conditions. Thriving tiny fish indicate a thriving ecosystem and saving 1,000 species from extinction depends on ensuring that they have thriving habitats. But now to the really good bit …

… an Aussie fish has been selected among the 10 global super stars. The Red-finned Blue-eye (RfBe)– go on, admit it, you’ve never heard of it - was originally found in just seven small artesian springs less than 8cm deep in central-western Queensland. It has a marvellous scientific name: Scaturiginichthys vermeilipinnis which means spring fish with red fins.

The RfBe is Australia’s smallest freshwater fish (25mm long at most) and is the only species in its genus. It is extremely sensitive to any environmental disturbance and was classified as Critically Endangered in 1996. By 2012 it was surviving in only three springs and was listed as one of the 100 most endangered species on the planet. It faced two main problems: degradation of its habitat by farming, particularly cattle and feral pigs, and the introduction from the US of the Eastern Gambusia or Mosquitofish in the early 90s in a bid to control mosquitos (really, how often can we make the same mistake?).

The Gambusia is highly aggressive to other small fish and competes with the RfBe for food and habitat. In no time at all, the US invader had spread far and wide and wiped out many of the vulnerable Blue-eyes.

In 2008, Bush Heritage purchased the former cattle station home of the RfBes specifically to protect them and the other 25 endemic species in the springs. Livestock, feral pigs and invasive plants have been removed, boundary fences installed, RfBes re-introduced to other springs in the area, and a method for breeding the fish in captivity developed. Most critically, the dreadful American marauders have been sent packing (not often you can say that!). The number of true-Blue Aussie battlers has increased from 1,000 to 5,000 since 2017.

Mea culpa: I confess that I pulled this article’s sub-heading out of the Tiny Fishes report.

Profitable poisons

In 2020, over 350,000 different chemicals were listed in 22 government inventories in 19 European and North American countries. There is no database of chemicals in active production globally, so we do not know how many are being produced around the world but it probably exceeds half a million. What we do know is that many of them are extremely harmful to human health, fatal even, but we have no idea how many or the full range of problems created because most have never been tested and the results of many of those that have been tested have never been made public.

Although the public has been aware of the dangers associated with many chemicals for decades (e.g., pesticides, plastics, asbestos, air pollutants, lead), it is only in recent years that most people have become aware of the health and environmental risks associated with the over 15,000 synthetic substances collectively known as PFAS compounds. This is despite two very well-known PFAS-containing products having been around for ages: Teflon (manufactured by Dupont) and Scotchguard (manufactured by 3M). And recent high profile, concerns about human exposure to fire-fighting foams probably mean that many people think only those if they do ever think of PFAS.

The three common features of PFAS chemicals are the almost unbreakable bonds between their carbon and fluorine atoms, their ability to spread rapidly in water, and their ability to last virtually forever. Consequently, they have spread all around the world and have entered most animals and plants. Every gram of PFAS that has ever been manufactured still exists somewhere.

The highest PFAS concentrations in the environment are found near manufacturing sites, waste dumps and military airports, although there is also concern about sewage sludge that is used as fertiliser. For humans, exposure mostly occurs via food or drinks associated with contaminated soil, water or packaging materials. Humans have no way of metabolising PFAS compounds and they build up in our bodies. They are associated with a wide range of serious illnesses.

Manufacturers have known for decades that PFAS chemicals accumulate in and are toxic to humans tissues and they have successfully utilised the tobacco company playbook of denial, undermining researchers who produce unfavourable research findings, disseminating favourable results from often poorly conducted research, spreading doubt, making generous political donations and lobbying against government controls.

In a glimmer of good news, last year 11 chemical company executives were jailed in Italy for up to 17 years for poisoning water and soil with PFAS chemicals.

Illegal gold mining in Congo

Over the last five years there has been a surge in illegal, semi-industrial gold mining in rivers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Driven by the rising price of gold, these operations are led by Chinese and Congolese nationals, facilitated by official corruption, embezzlement and mismanagement and protected by Congolese army and police officers – all in a country that suffered some of the worst experiences of European colonisation.

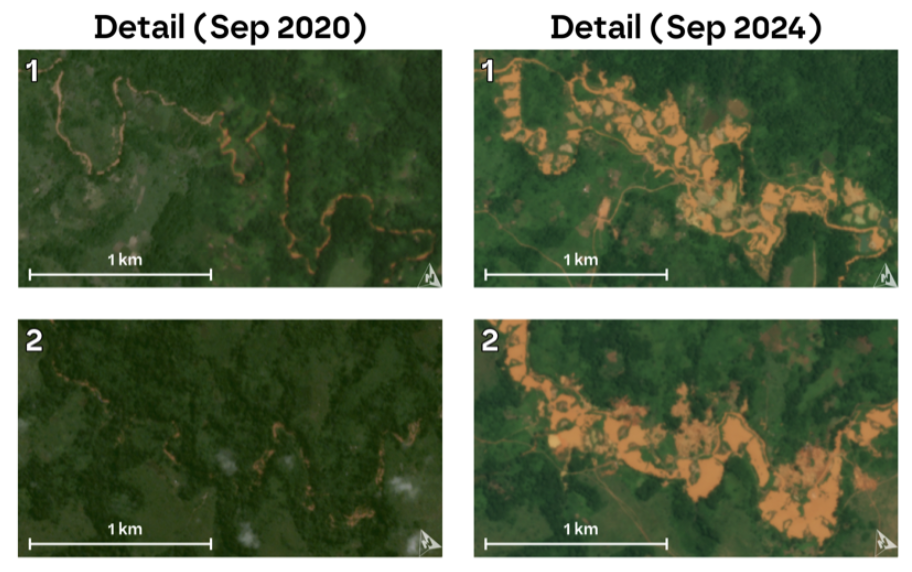

The rogue miners excavate areas 50-400 metres wide along long stretches of riverbed, destroying the river and its banks before moving on and leaving long chains of flooded mining pits, illustrated in the aerial photographs below. The degraded rivers and creeks eventually flow into the River Congo.

Apart from the theft of Congo’s natural resources (neither local communities nor the national economy benefit much), the illegal mining creates numerous human and environmental problems. For instance, the mines and associated infrastructure, particularly roads, destroy the tropical rainforest and rivers, both of which are polluted by toxic chemicals such as mercury and cyanide, with consequent loss of biodiversity. Local Indigenous communities are subjected to abuse of their human rights and loss of traditional lifestyles, including access to clean water and land for farming. The promise of easy money also leads to armed violence between rival militias.

World is getting hotter and less cold

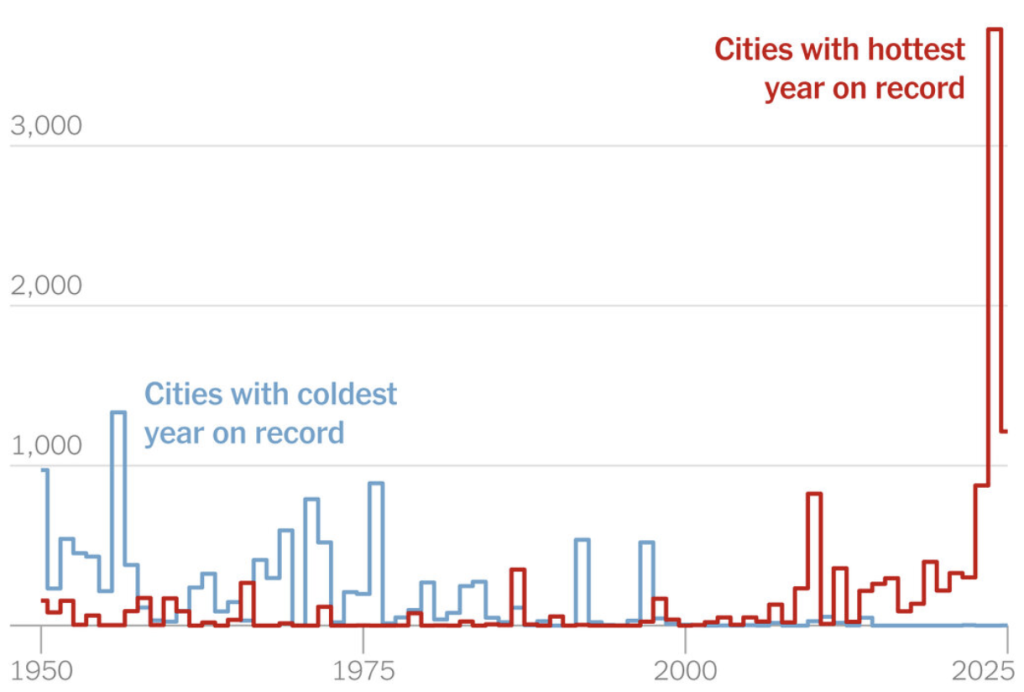

I can hear your “Duhs” and sense your eyes rolling but stay with me. Even if the cold days and cold places stayed just as cold as they were, the world’s average temperature would still go up if the hot days and places got hotter. But that theoretical scenario is not happening. In cities around the world, record high temperatures are increasing and record low temperatures are disappearing.

The histogram below shows that between 1950 and about 2000, the number of cities with populations over 50,000 that experienced record low temperatures were much more common than cities that experienced record highs. Since about 2010, however, the cities experiencing record highs have greatly outnumbered those with record lows. Last year, Manvi in India was the first city since 2014 to experience a record low.

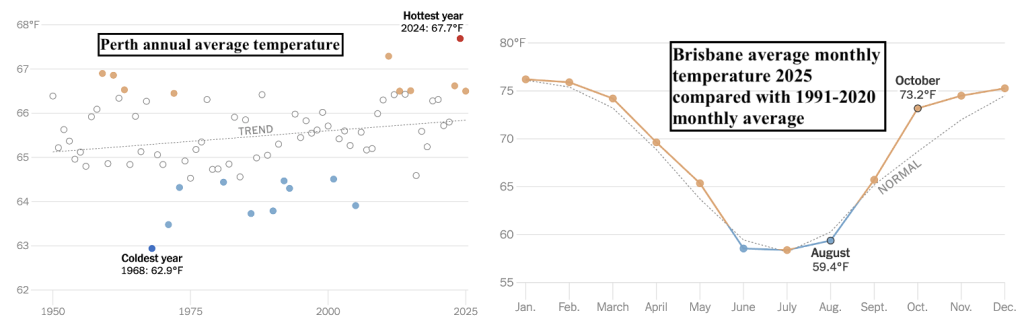

It’s interesting to examine last year’s average monthly temperature (oF unfortunately) and the average annual temperature since 1950 for Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Brisbane – illustrated below to encourage you check out the link.

Of course, none of that suggests that there won’t ever be any extremely cold weather as the world heats up. Although it may mean that societies are less well prepared for it.

World’s smallest vertebrate

The smallest of the ten tiny fishes is the Indonesian Superdwarf Fish which grows to a maximum length of 10mm – that’s about the distance across the nail on your little finger – and is (arguably) Earth’s smallest vertebrate. It’s not easy getting everything you need to be a vertebrate into such a small body and so the adult Superdwarf retains some of the features that are characteristic of young fish, never develops some body parts that other adult fish possess, has a simplified skeleton with fewer bones and even has a pared back genome.

The Superdwarf lives in peat swamps in Sumatra and Bintan. These are low in nutrients and oxygen and the surface water often dries out. The swamps can also be as acidic as vinegar. That sounds tough to us, and to most other fish, but it’s home for these tiddlers. Unfortunately, it’s a home that is rapidly disappearing as it is drained for palm oil plantations and ravaged by fires.