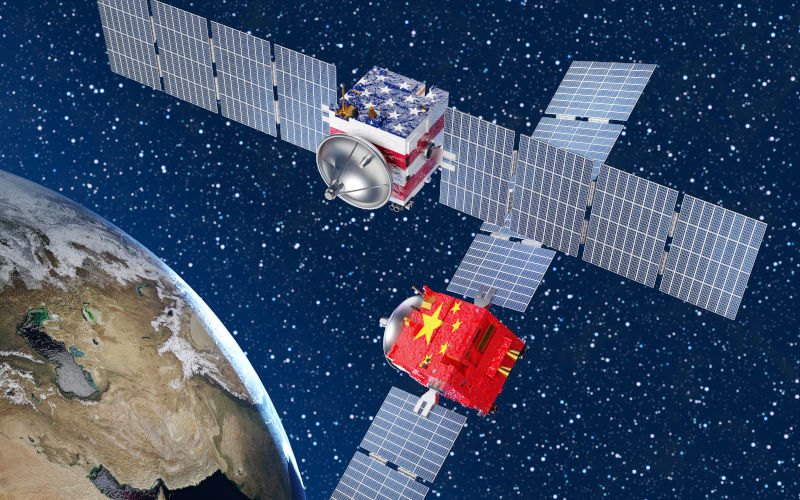

Starlink, China and the governance of low Earth orbit

February 23, 2026

China’s massive satellite filings highlight how low Earth orbit has already been transformed by industrial-scale deployment – and how existing governance is struggling to keep pace.

In late December 2025, China filed applications with the International Telecommunication Union covering satellite constellations totalling more than 200,000 satellites. The scale of the filings was framed in media coverage as escalatory and hypocritical, given Beijing’s earlier criticism of SpaceX’s commercial satellite constellation Starlink. Yet the move reflects an orbital environment already transformed by large-scale commercial deployment, where control over satellite infrastructure has potentially profound political consequences.

Low Earth orbit has shifted from a sparsely populated technical domain to a dense layer of critical infrastructure. More than 10,000 active satellites now circle the planet, with the majority launched after 2019, supporting civilian communications, navigation systems, military operations, disaster response and commercial connectivity. This transformation has been driven by falling launch costs, the industrialisation of satellite production and the capacity of a small number of actors – notably SpaceX – to deploy systems at scale.

Starlink matters not simply because of its size, but because it became embedded in civilian, military and emergency communications before governments had fully understood the implications. In Ukraine, Starlink terminals were integrated into battlefield communications out of necessity rather than deliberate policy choice. And in other conflict-affected regions like Iran, satellite connectivity has become politically consequential because access can be enabled, restricted or delayed through operational decisions rather than formal state policy.

Starlink’s significance lies less in the discretion of its owner than in the structural features of dense orbital infrastructure. Once deployed, satellite systems are difficult to replace or unwind. Reliance on this system has developed faster than the rules meant to govern it.

China’s commercial satellite sector has changed markedly in response to these pressures. Manufacturing has moved away from small-scale testing and custom production towards faster, more standardised output. Firms such as GalaxySpace have reorganised factories to shorten build times and increase volume. Design choices once driven by experimentation are now shaped by the practical demands of launch schedules, including restrictions on how many satellites can be stacked inside a single rocket and the need to meet regulatory filing deadlines.

These changes are closely tied to International Telecommunication Union rules, which impose deployment timelines on filings and penalise failure to act. Chinese engineers and executives are explicit that manufacturing capacity already exceeds launch capability, making access to rockets the main constraint. Large filings do not necessarily translate into a commitment to deploy hundreds of thousands of satellites at once but are a way of keeping future options open while launch capacity catches up.

Different institutional responses to this scaling problem have emerged in the United States and China. SpaceX addressed it through vertical integration, bringing rockets, satellites and terminals within a single firm and allowing rapid feedback between design and deployment. The US government adapted by becoming both a customer and an operational partner of SpaceX, relying on contractual access rather than direct control.

China has followed a different path. Satellite production, launch vehicles, chips and downstream applications remain distributed across specialised firms, many of them state owned or state supported, and coordinated through policy frameworks rather than a single corporate hierarchy. This structure slows iteration at the firm level but allows resources to be concentrated once deployment becomes a national priority.

Despite these differences, both paths converge on the same outcome. Low Earth orbit is filling quickly, driven by existing regulatory incentives and falling costs. Chinese industry reports suggest that the safe carrying capacity of low Earth orbit may have already been exceeded by current and planned satellite constellations. But restraint carries its own risks. For states arriving late to large-scale deployment, holding back does not preserve an open and uncontested commons – rather, it increases the likelihood of dependence on systems built by others.

This dynamic exposes a deeper mismatch between the pace of technological change and the assumptions built into space governance. Existing frameworks were designed for an era of infrequent launches, limited satellite numbers and state-led programs. They were not built to manage industrial-scale constellations produced on assembly lines and launched dozens at a time. The result is a system that rewards early deployment and continuous expansion, while offering few mechanisms to manage congestion after the fact.

China’s filings should be interpreted less as a bid for orbital dominance than as an effort to avoid dependence in an environment already shaped by early movers. Chinese firms are racing to demonstrate that large-scale satellite constellations can be manufactured, launched and operated within existing international filing and deployment rules. This is because control over dense orbital infrastructure carries political consequences once it becomes embedded in communications systems. The sheer volume of planned deployments reflects an understanding that once orbital space becomes physically saturated, late entry risks locking states into reliance on systems they do not control.

Space governance is increasingly shaped by infrastructure, not the other way around. As dense satellite networks become integrated into economic and security systems, access, capacity and resilience are increasingly determined by how these systems are used and managed, rather than by negotiated limits. Low Earth orbit is no longer a distant frontier but an established layer of infrastructure, and institutions designed for a slower and less crowded era are struggling to govern a domain already reshaped by scale, speed and industrial momentum.

Republished from East Asia Forum, 19 February 2026