The smouldering wreckage on Capital Hill – part 2

February 4, 2026

The Liberal Party faces a structural dilemma – it cannot govern without the Nationals, yet governing with them pushes it further from the voters it needs. As support for the major parties erodes, Australia is edging towards a more fragmented political future.

The political aphorism for the start of the 2026 year is that the Liberals cannot form government without the Nationals, and that they can cannot form government with them.

The first part seems to be right – the only time in recent history when the Liberals had a House of Representatives majority – 68 seats in the 127-seat chamber – was after the 1975 election. The prospect that the Albanese government would do anything that verged on the incautious daring of the Whitlam government is too hard to imagine, as is the prospect that Government-General Sam Mostyn would conspire with a foreign monarch to unseat an elected Australian government.

How about the other possibility – getting back together with the Nationals, and doing some preference deals with One Nation, to pursue a Farage/Trump populist right-wing agenda? Consider those poll averages: Coalition plus One Nation = 46 per cent. That’s better than Labor + Green = 42 per cent.

But it doesn’t work like that, and the numbers people in the Liberal Party know it. For a start, apart from a few Coalition seats held on the outer urban fringes, neither the Coalition nor One Nation have a strong urban base, in a country where two-thirds of the population live in big cities – cities with large immigrant populations and where people have increasingly turned away from established political parties.

On Radio National Linda Botterill put the issue in the way that a detached Liberal Parry strategist might. Perhaps it’s the way Menzies saw it in 1944 when he built the Liberal Party out of the smouldering ruins of the United Australia Party. Botterill captures the same spirit:

“Maybe the Coalition has run its course as a marriage, and needs to be something much more flexible. If they are two independent parties they do need to be acting like independent parties. In international terms the Australian Coalition is an absolute anomaly. Everywhere else in the world when minor parties go into coalition they do so after an election in order to form government and they negotiate around points of policy, the composition of their ministries and so on.

“Looking at One Nation as a threat suggests a move to the right politically by the Coalition. That’s not going to do the Liberals any favours in those seats that it needs to win in the inner cities.

“The Liberals really copped a walloping at last year’s election. Being in coalition with the Nationals, particularly as the Nationals are showing every inclination of moving to the right, is not going to help them win those seats back.

“Both parties would see that they’ve got very little chance of beating Albanese at the next election, whether they’re in coalition or not. So this looks like a really good opportunity for the Liberals, particularly, to do some policy soul-searching and work out exactly what their values are and what they stand for, and then go back into coalition when they’re ready in a much stronger position.”

Botterill’s prescription for the Liberals is right, and Jason Falinski makes much the same point: the Liberals should go it alone and see if the Nationals want to join them. But the trouble with Botterill-Falinski prescription is that the decision will be made by the Liberal Party’s survivors in Parliament, a caucus that excludes “moderates” such as Falinski and others who lost their seats.

Shoving the National Party off to the la-la land of One Nation deals with only one part of the Liberals’ problem, because within the ranks of the surviving Liberals are those who want to take their party in the same direction. As Turnbull puts it in a Saturday Extra conversation with Nick Bryant, these are the people he describes as the “angry populist right”, whose policy views are reinforced by the culture war battles played out on Sky News. (He describes Sky News as “the best thing that ever happened to the Labor Party”).

So the media talk is of a challenge to Sussan Ley’s leadership. Although the petulant behaviour has been by the Nationals, Ley has become the scapegoat for the Coalition’s problems.

And then there’s gender: surely it’s a bit off for the Liberal Party, the party of real men, to be headed by a woman. So like two stud bulls fighting for dominance in a small paddock, two men are getting ready for a challenge. One has been spending his time developing weird and internally contradictory economic theories, and the other has been dog-whistling ideas about a return to White Australia, but they are united in their visceral hatred of renewable energy and in their gender. Just to be helpful, Tony Abbott is urging them to decide between them who is going to rid the Liberal Party of Sussan Ley.

Speaking on The Guardian’s “Full Story” podcast, Malcolm Turnbull describes the Liberal Party’s problems – problems they have brought down on themselves, largely because the party’s right has immersed itself in the Sky News bubble. He is critical of Ley for having caved in to the right after the Bondi murders. But he doesn’t join the chorus calling for her to be replaced: the pool of talent to lead the Parliamentary Party “is not enormous”, and there is no assurance that changing the leader will solve its problems.

The irony of the challenge to Ley’s authority is that she is probably the model of a National Party MP. Her Farrer electorate, stretching from the Snowy Mountains to the South Australian border, is about as rural as you can get. She has worked in woolsheds, she has been a stock mustering pilot, she has lived on a farm with her husband. But she is being challenged by members of a party whose caucus is dominated by former police officers, salesmen and others with desk-bound occupations – people who would feel lost in a woolshed, who have never saddled a horse, and who wouldn’t know the difference between a flap and an aileron. Mark Kenny and Judith Brett explained on Late Night Live that although its members have adopted Akubra hats as cultural symbols, their constituency is the mining industry, particularly the coal industry. It’s a long time since it was the Country Party.

A more detached view – the end of Westminster

Since Trump’s inauguration (was it really only a year ago?) Australians have watched with wonder as the US slides into authoritarian dictatorship. How could this happen in a country with a constitution specifically designed to entrench the separation of powers? Apart from some quaint habits – using an incomprehensible system of weights and resting in lavatories – Americans aren’t all that different from Australians, but they have created a political disaster for themselves, largely because they have solidified an impenetrable two-party system. Isn’t it obvious that they need an independent electoral commission, ranked-choice voting, and compulsory voting – none of which are constitutionally proscribed?

The answer lies in the inertia of political traditions, such as their party primary systems. In any country there is huge institutional investment in political systems – by political parties, by public servants, by academics, and by the media.

A foreigner – say from Germany or the Netherlands – looking at our systems may observe that although in Australia we have a constitution that says nothing about political parties, oppositions, shadow cabinet, bipartisanship, or the Westminster system, our political parties, and our political class, including journalists and academics, behave as if we do have a constitutionally prescribed Westminster two-party system.

That’s a system borrowed from a country with a different history and a different culture. In its time Westminster did a reasonably good job when the main political differences were on lines of economic class, and when there was a basic settlement on which the dominant parties agreed. But it falls down in complex democracies where there are many lines of political differences to be resolved.

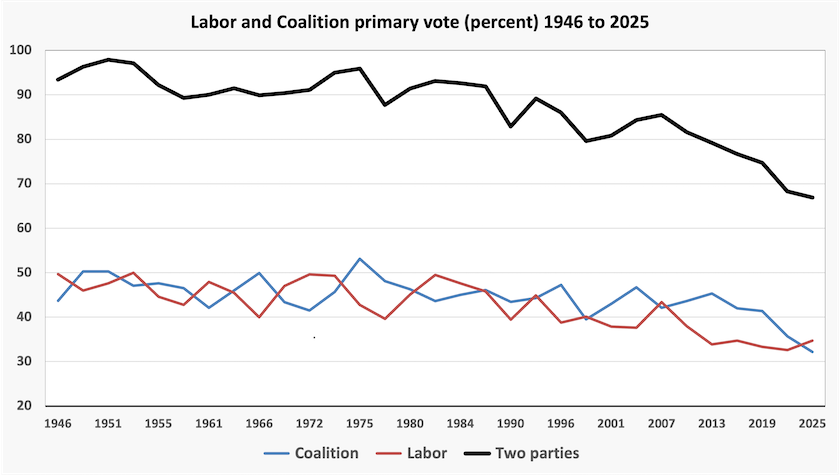

Our foreign observer might look at our long-term electoral history in terms of the primary vote for the two parties, going back to 1946, when the two-party system was established, minor parties on the right having been absorbed into the Liberal-dominated Coalition. (I have been showing this graph in previous roundups, and each time the lines descend a little more.)

At last year’s election the combined Labor-Coalition vote fell to 67 per cent, meaning that one-third of voters went for some other party or for someone else. In doing so they managed to get 15 independents and ‘minor’ party members elected to the 150 seat House of Representatives.

Let’s turn back to that table based on opinion polls, and add the Coalition and Labor votes. Their combined total, based on the poll averages, is 56 per cent – 11 percentage points down from the election.

It’s hard not to conclude that Australia is well along the path to becoming a multi-party democracy.

In fact we’ve already been there. Labor had to deal with it in 2010 when it formed a minority government negotiated with support from independents. The present Labor government, holding 94 of the 150 House of Representatives seats has not had to confront the prospect of minority government.

It’s an issue for parties on the right, however, as Casey Briggs explains in a post, where he outlines the options for the parties on the right – basically to re-unite or to go their own way. He also suggests there is an Option C, which is “the beginning of something bigger”.

Although he doesn’t specify it, that something bigger could be a departure from assumed ’left’ or ‘right’ coalitions of any sort.

Liberals, Nationals, and many in One Nation are still thinking in terms of a ‘right’ coalition, and indeed that is a common pattern in many countries, including New Zealand. The trouble with that model is that when the right tries to form a coalition, it has to move further and further to the right to bring in supporters, and those on most extreme fringes enjoy disproportionate power in negotiations. That winner-take-all (and more) model doesn’t work out well in a democracy like Australia where the dominant public mood is centrist.

It doesn’t have to be that way. There are other patterns in European democracies, where parties on the left and right agree to rule out forming coalitions or deals with parties on the extreme fringes, such as the Communists and Alternative für Deutschland. In fact just in the last few days in the ACT, the Liberals and the Greens have been quietly talking about forming government. At this stage it’s not a serious proposal, but it’s a reminder to the long-standing Labor minority government that there is no one pattern of coalition formation.

Is our wider political establishment ready for such thinking?