Cutting through the spin – Ten logging 'myths' in the new ABARES report

August 26, 2025

Australia’s native‑forest debate has long been characterised by falsehoods generated by industry and arms of industry such as parts of government.

The Australian Government’s latest Insights report repeats many of them. Below I set out each claim in the latest report as a myth and summarise the peer‑reviewed science and economics that shows why it doesn’t stack up.

Myth 1 Only 0.05 % of native forest is harvested each year – impacts are trivial

Reality: Some forest types have been heavily targeted for logging for many decades and are now heavily modified. In Victoria’s Central Highlands, an intact patch is now, on average, just 71 meters from a logged or otherwise disturbed patch. Habitats are fragmented with major cumulative impacts on species such as the Critically Endangered Leadbeater’s Possum. Long‑term monitoring shows landscape‑scale declines in possums, gliders and birds, even where the yearly cut looks modest on paper.

Myth 2 Most harvesting is ‘selective’ and leaves habitat trees, so wildlife is protected

Reality: Clearfelling operations remain the norm in many kinds of forest. After a coupe is felled, many of the most important structural components of a forest are simply gone. Court evidence found VicForests’ “variable‑retention” coupes retained too few trees for Greater Gliders; most animals present before harvest were predicted to die afterwards. Comparative studies show both clearfell and selective logging simplify forest structure, remove hollows and drive similar fauna declines. Within regenerated coupes, tree‑fern density can collapse by up to 96 % and field surveys show that most animals on logged sites die during or soon after operations.

Extensive soil disturbance across a steep slope on Taungurung Country Image supplied/Chris Taylor

Myth 3 Native‑forest logging targets high‑value sawlogs, veneer and poles

Reality: Production data reveal that ≈90% of logs from native forests now become pulp or export woodchips. Accounting for the whole tree, barely 4 % of the original forest biomass emerges as sawn timber; 60 % is left as slash and another 29 % becomes pulp and paper. The industry is, in practice, pulp‑ and wood‑chip‑driven.

Myth 4 Sustainable harvesting allows forests to regrow; long‑term values aren’t compromised

Reality: The evidence is overwhelming that long-term biodiversity values are significantly eroded. In addition, regeneration failure is widespread. Field audits across 300 Victorian coupes show ~30 % fail to regenerate to eucalypt forest even after burning and reseeding. Regrowth sites carry depleted soils, hotter daytime temperatures, drier conditions and few hollows for wildfire for many decades, leaving them biologically impoverished for centuries, not decades.

Myth 5 Cut**‑and****‑regrow harvesting boosts carbon uptake**

Reality: Old‑growth Mountain Ash stores >1 865 t C ha⁻¹ – among the highest carbon densities on Earth. Logging releases up to 60% of that carbon immediately and exchanges centuries‑long storage for short‑lived products and slash burns that add to the atmosphere.

Myth 6 Logged forests still store carbon, and wood products offset emissions from steel and concrete

Reality: The carbon debt from felling mature eucalypts takes many decades to repay, if ever.

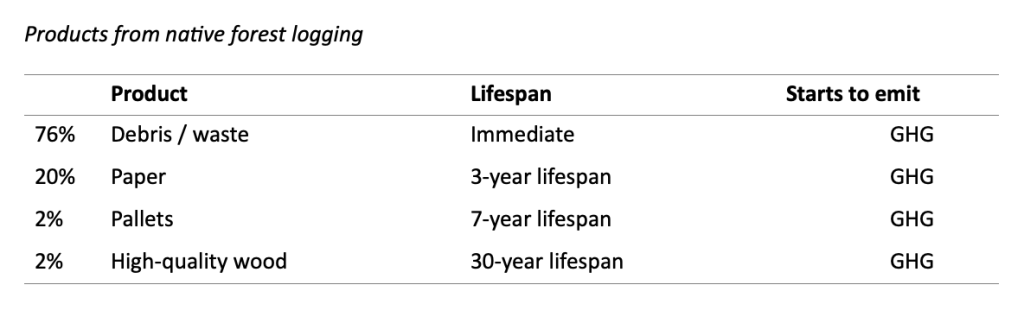

Of the 40% taken out as logs, half becomes paper products (20% of initial biomass), with an average lifespan of three years before going to landfill to generate greenhouse gas emissions. 2% of the initial biomass becomes pallets (maximum lifespan of seven years); and 2% becomes high-quality timber (average lifespan 30 years); the rest (16% of the initial biomass) is debris. Life‑cycle analyses show genuine long‑lived products are better sourced from plantations with far lower emission intensities.

Myth 7 ‘There’s no unequivocal evidence that harvesting increases bush‑fire risk’

Reality: Repeated analyses show fire severity peaks in young logged stands and declines as forests age. Post‑Black‑Saturday analyses demonstrate that high‑severity fire is most likely in 0‑ to 40‑year‑old regrowth and least likely in mature, unlogged forest. Mechanical “thinning” or “forest‑gardening” can actually increase the risk of high-severity wildfire by opening the canopy and increasing surface fuels.

Myth 8 ‘Sustainable wood supports regional jobs and industries’

Reality: Native‑forest operations now run at a net public loss once hidden subsidies and environmental liabilities are counted, while employment has shifted overwhelmingly to plantation processing and nature‑based tourism. By 2018, 87 % of Australia’s sawn timber already came from plantations; in NSW and Victoria the figure is ≈ 88 %.

Myth 9 ‘Forest area has increased since 2008 – clearing is yesterday’s issue’

Reality: Australia remains a global deforestation hot‑spot, clearing c. 500 000 ha yr⁻¹. Less than half of the continent’s pre‑1788 forest and woodland cover remains; in fact, logging and clearing has increased dramatically in recent years in New South Wales. What has “increased” since 2008 is mainly young regrowth on previously cleared farmland, not a return to complex old‑growth ecosystems.

Myth 10 ‘Native‑forest harvesting can coexist with conservation and climate goals’

Reality:

Ongoing logging fragments ecosystems, elevates catastrophic‑fire risk for decades, generates major carbon emissions and negative affects many native plant and animal species. These impacts directly conflict with Australia’s commitments to end extinctions and cut emissions.

Conclusion

The weight of modern science tells a consistent story: ending industrial native‑forest logging is a triple dividend – for biodiversity, the climate and regional economies that can pivot to plantation timber, carbon stewardship and tourism. Clinging to myths to support ongoing native forest logging only delays that transition and deepens the ecological and economic debt we leave future Australians.

The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Pearls and Irritations.