Celebrating war crimes is a moral failure, not cultural pride

December 5, 2025

From ancient Rome to modern Melbourne, societies have repeatedly transformed civilian suffering into spectacle. Celebrating violence against the innocent is not a cultural quirk – it is a profound moral collapse.

There are many things in human history that stretch the imagination: pyramids aligned with constellations, the global obsession with celebrity cooking shows, and – most mystifying of all – people holding parties to celebrate the killing of innocents. Of all the explanations for this delightful human pastime, “moral health” is certainly not one of them.

The most recent example is depressingly familiar. On 17 September 2024, thousands of pagers carried by Hezbollah members – and, crucially, by civilians who simply lived or worked near them – exploded simultaneously across Lebanon and Syria. The next day, walkie-talkies detonated. Thirty-nine people were killed. More than 3,400 were wounded. Children, shopkeepers, commuters, and ordinary people with no connection to Hezbollah were maimed or permanently disabled. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu later confirmed he personally approved the operation, and the UN’s human rights chief, Volker Türk, stated what international law already makes clear: booby-trapping everyday civilian objects is a war crime. It is the sort of behaviour humanity supposedly outgrew sometime around the Middle Ages.

And yet, in Melbourne, a local Zionist Jewish group decided that this mass maiming of civilians deserved not reflection, nor mourning, nor even grim silence – but a family day celebration. A picnic. A child-friendly tribute to what the organisers proudly described as one of Mossad’s most “cunning missions”. One can only imagine the activities: balloon animals shaped like pagers, face-painting in shrapnel patterns, perhaps a jumping castle labelled ‘Permanent Disabilities’. The fact that such a scene is even conceivable tells us something about the mental gymnastics required to cheer for violence against the innocent.

Many Australian Jews were horrified. Sarah Schwartz of the Jewish Council of Australia voiced concerns about children being drawn into “militarised discourse” and taught to cheer for acts the UN has explicitly condemned as unlawful. That this needs to be said in 2025 is an indictment of our moral trajectory.

Unfortunately, Melbourne has not invented anything new. Humans have a long tradition of not only inflicting violence but polishing it, framing it, packaging it, and inviting the public to applaud.

In ancient Rome, families flocked to amphitheatres to watch enslaved men disembowelled for entertainment. In medieval Europe, public executions functioned as cheerful community events – complete with musicians, street vendors, and disappointed spectators when the condemned died too quickly. Colonial armies, upon annihilating Indigenous communities, often toasted their “victories” over the bodies of the people they had just dispossessed. Even Nazi Germany, though stylistically colder, celebrated its “achievements”: emptied towns, deportation quotas met, cities declared “cleansed”. The absence of confetti hardly absolves anyone.

What kind of mind celebrates the deaths of civilians? Psychologists point to several mechanisms, none of them flattering. Dehumanisation lowers the emotional cost: if the victims are portrayed as less than human, their suffering seems irrelevant. Moral disengagement reframes violence as justice or necessity, allowing people to feel righteous while applauding a war crime. Group identity can be so intoxicating that cruelty becomes a bonding ritual – a way to demonstrate loyalty to the in-group. And then there is cognitive dissonance: when people support something horrific, celebration becomes a psychological shield. If we cheer loudly enough, maybe it won’t feel like a crime.

Interestingly, no other species behaves this way. Lions do not hold barbecues after taking down a gazelle. Wolves do not clap in unison. Sharks do not nudge each other with a wink as they circle their prey. Animals kill to eat, to survive, to protect territory – not to affirm tribal identity, prove ideological superiority, or entertain the family. The celebration of brutality is a uniquely human invention, one of our most shameful contributions to the universe.

Let us be clear: grieving for one’s own dead is human. Condemning the crimes of one’s enemies is human. But celebrating the deaths of civilians – children, neighbours, strangers walking to school – is something else entirely. It corrodes whatever remains of moral credibility and pushes a society toward a form of ethical gangrene. When an event in Melbourne invites children to cheer for wounded Lebanese civilians, this is not community building, nor cultural pride, nor even political advocacy. It is the normalisation of sadism disguised as civic engagement.

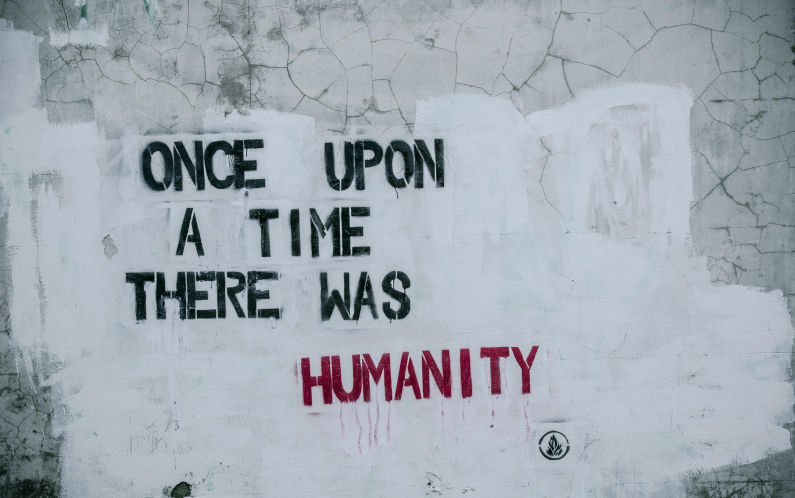

And it is a warning: that once cruelty becomes something to celebrate, humanity steps closer to becoming the very thing it pretends to fear.