A descent into violence? Political polarisation in the US

July 15, 2024

Can the United States avoid a descent into political violence? Of the 52 cases where countries reached the levels of polarisation which now exist in the US, half had their status as democracies downgraded. The US is the only Western democracy to have sustained such intense polarisation over such an extended period. It really is in uncharted territory.

A repost from July 29, 2023

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

…

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

W B Yeats The Second Coming

And what rough beast slouches toward Washington be born again? (with apologies to Yeats)

Introduction

Polarisation, and its boon companions, populism and conspiracy theories, have grown with remarkable speed since the turn of the century. On the left this has been mirrored by the surge in “woke” moral intolerances and cancel culture. If sustained, these trends are judged, at the minimum, to make US governance less effective. At the worst they could lead to political violence and increasing tension between Republican states and any Democrat President.

There have been pale “woke”, populist and conspiratorial echoes in Australia.

It is important for us to consider the consequences of polarisation for the US polity, its domestic and foreign policies and its stability as a key strategic partner. And there are lessons for us about what we need to do to avoid the risks of a parallel descent into civil rancour.

Growth in conspiracy theories

Anxiety and feelings of powerlessness provide fertile ground for growing conspiracy theories, while the internet and social media provide water and fertiliser. Conspiracy theories are a way of understanding the world that legitimises the status of believers. Conspiracy theories have a synergistic relationship with political polarisation - they both reflect it and drive it. Every period of economic and social turmoil has seen a rise in conspiracy theories and widescale threats to democracy often unfold.

Americans (and Australians) have a comparatively high belief in conspiracy theories. YouGov polling suggests that 31% of Americans (but only 10% of Danes) believe that, regardless of who is officially in charge of governments and other organisations, there is a single group of people who secretly control events and rule the world together. This pattern is repeated across other classic conspiracy theories.

What is radically different in the US is the way in which politicians, particularly Republicans, have begun to lean in to those conspiracies - even when they don’t believe them. President Trump routinely raised conspiracy theories about his opponents (Obama “birtherism”, Clinton “body count claims”) and shadowy organisations trying to frustrate his efforts on behalf of his loyal supporters (the “deep state”) along with a host of others which disparaged scientific and expert advice like the “global warming conspiracy”. The most threatening to democracy was the false claim of a stolen election.

Providing air to conspiracies to win support from their adherents is always a risk in democracies which by their very nature are competitive. But in Western democracies there had been an unwritten convention that this shouldn’t be done by politicians who aspire to national leadership - that has virtually disappeared in the US.

Rise in political violence

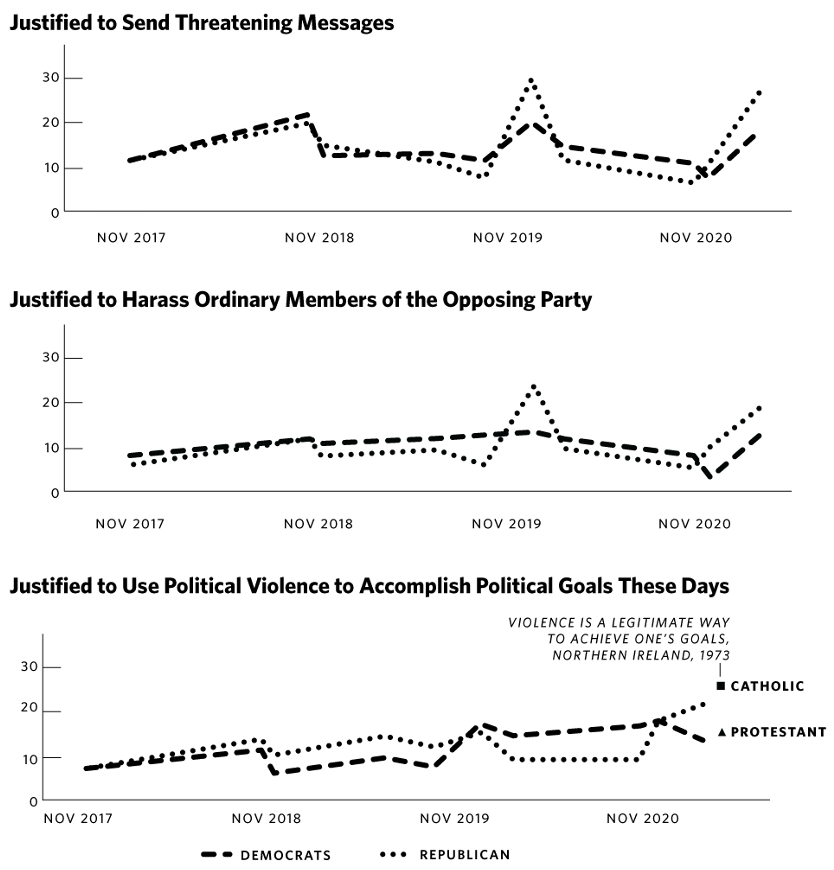

The rise in polarisation has been reflected in an extraordinary growth in beliefs that political violence can be acceptable and an alarming rise in threats and actual expressions of violence toward political opponents since 2016. This is very worrying in a country where 44% of households own a gun.

In their submission to the Select Committee to investigate the January 6 2021 attack on the Congress the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace presented the following evidence:

It is particularly worrying that the proportion of people seeing violence as a legitimate way to achieve political goals is approaching levels seen during Northern Ireland’s “Troubles” - years marked by barely suppressed civil war and terrorism.

Carnegie further presented statistics on actual or threatened violence.

Threats against members of Congress

Threats against members of Congress are more than ten times as high as just five years ago. From 902 threats investigated by Capitol Police in 2016, they leapt to 3,939 in the first year of the Trump presidency, 5,206 by 2018, 6,955 in 2019, 8,613 in 2020, and hit 9,600 in 2021.9

Armed Demonstrations

“In the 11 weeks between the election and Inauguration Day, armed actors at protests grew by 47% compared to the 11 weeks prior to the elections, and organised paramilitary groups grew by 96%”

What has happened in other democracies with similar levels of affective polarisation?

The results are not encouraging. Polarisation at the level which has now existed in the US for many years is bad for democracy. Of the 52 cases where countries reached US levels of polarisation half had their status as democracies downgraded. Only 9 managed to reduce polarisation sustainably. The US is the only Western democracy to have sustained such intense polarisation over such an extended period. It really is in uncharted territory. (McCoy and Press: What Happens when Democracies Become Perniciously Polarised).

There must be some risk that polarisation passes a critical mass which sees the state’s coercive apparatus (the FBI, and other Federal law and order agencies) forever battling low or even high level insurrections by disaffected militias.

If America’s elites do not manage to see enough common ground to reduce the obvious inequalities and identity tensions, we could be about to experience a sustained period of dramatic swings in policy - both domestic and international. Nations living through serious internal tensions can either withdraw and become isolationist, or riskily plunge into jingoism and foreign adventures in the hope that patriotism will bring the nation together.

View all the articles in this five part series.

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/political-polarisation-in-the-united-states-the-series/