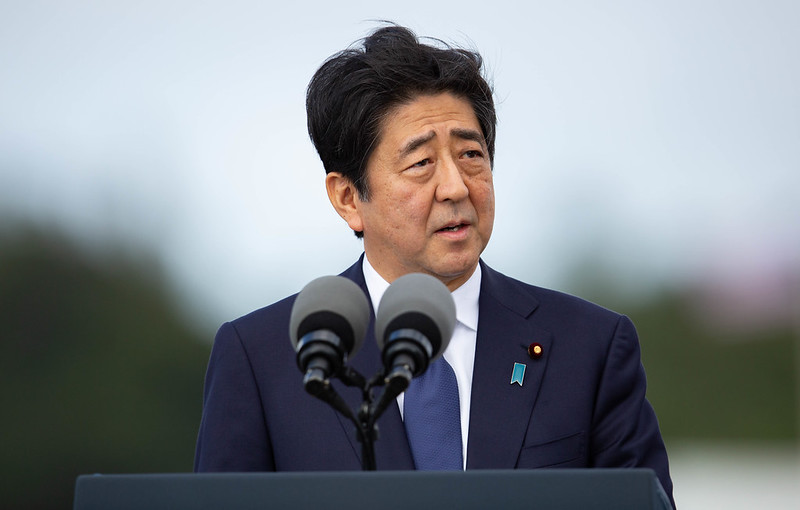

Abe Shinzo The ambiguous legacy of an assassinated Japanese Prime Minister

August 20, 2022

When former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo was shot and killed in front of an election rally in Nara on 8 July, two days before an Upper House election, shock waves spread quickly around the world.

Following a private funeral, Prime Minister Kishida announced that a state funeral for Abe would be conducted on 27 September. It would demonstrate that Japan would not submit to terrorism and it would publicly recognise Abes long contribution to the country, especially as Prime Minister in 2006-7 and in 2012-20

Some began to draw dark parallels with the assassinations (and attempted assassinations) of Prime Ministers and former Prime Ministers in pre-war Japan, of Hara Takashi in 1921, Hamaguchi Osachi in 1930, Inukai Tsuyoshi in 1932, Saito Makoto and Takahashi Korekiyo in 1936. Others recalled even more darkly the Aum shinrikyo (Aum Supreme Truth) cult that attracted most attention and ended in disaster following the March 1995 sarin chemical attack on the Tokyo subway and the arrest, trial, and execution of its key members in following years. Might 21st century Japan be on the verge of going off the rails again now as it did with such consequences during other, troubled times?

Though regarded highly outside Japan, especially in Washington where he was appreciated as the most reliable (or obedient) of allies, within Japan such was the miasma of scandals that thickened around his government that one expert (Kyoto Seika Universitys Shirai Satoshi) could refer early in 2020 to his (then) more than seven years-long government as accomplishing little and failing nearly all of its policies, a stain on Japans history. Such stern judgement was rare outside Japan, however, where it tended to be swallowed by a global wave of admiration and sympathy, of which perhaps typical was former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who said The world will miss Abes wisdom, Shinzo Abe was sincere, authentic and warm. He was calm, considered, and wise Expressions of sympathy came even from those far removed from Abe on the political spectrum, including Vladimir Putin, who had good reason to know Abe well since he had met him for high-level talks on no less than 27 occasions, far more than any other state leader. Putin expressed shock at the irreparable loss of an outstanding statesman.

However, the decision to conduct a state funeral soon proved controversial. Nation-wide majorities recorded their opposition, often by large majorities. As of late July a Nikkei poll found 47 per cent opposed as against 43 in favour while another survey, by Kyodo, found 53 against and 45 in favour. Further surveys confirmed and enforced this negative trend.

Attention began to focus on the connection between Abe and the far-right or ultra-rightist Unification Church (Toitsu kyokai), currently known as World Peace and Unification Family League or as Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity, or simply as the Moonies after founder Moon Son Myung. Abes killer, the 41-year-old former Maritime Self-Defence Forces member, Yamagami Tetsuya, declared that he had decided to punish Abe because he believed him closely connected to this cult and therefore responsible for his familys immiseration when his (Yamagamis) mother contributed the familys hundred-million-yen (one million dollar-plus) savings to the Church, having come to see founder Moon as a divinely appointed Messiah, parent to humanity, whose mission was to complete Christs work and create a pure and perfect order on earth. The family impoverished and isolated, Tetsuya’s father and two of his brothers committed suicide and Tetsuya himself had planned to do likewise.

One offshoot of the Church was the International Federation for Victory over Communism, instigated in 1968 by Moon in conjunction with Taiwans Chiang Kai-shek and Japanese ultra-rightists Kodama Yoshio and Sasakawa Ryoichi, strongly promoted by Abes grandfather, Kishi Nobusuke [1896-1960; Prime Minister, 1957-1960]. With the anti-communist cause resonating positively in the US and in Japan, the Church thrived.

Kishi Nobusuke had indeed been a close associate of the Church founder, Moon, and Abe, his grandson, seems to have maintained that closeness, delivering a keynote welcome message to the Universal Peace Federation (an offspring of the Church) for its September 2021 meeting. Many other members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and its governments likewise had Church connections. Abes younger brother, Kishi Nobuo, Minister of Defence from 2020 was replaced in a cabinet reshuffle on 10 August after admitting that he had enjoyed the assistance of members of the Church in his election campaigns. Six others, however, remained in office. Weeks after the assassination, Japanese media reported that the names of 106 Diet members appeared on Church membership lists. Of these, 82 were LDP members. Nineteen of the 54 members of the reorganized Kishida cabinet of 10 August 2022 had Church connections. Furthermore, apart from the Church and the Nihon Kaigi, virtually all members of the Kishida cabinet belonged to the Shinto Politics League (essentially a restatement of pre-war and wartime State Shinto).

The astonishing fact is that from the late Abe Shinzo through the Suga Yoshihide and Kishida Fumio government periods (2019-2022) Japan had a government that was one half Korean-based Unification Church and one-half Japanese ultra-nationalist, Nihon Kaigi. The former was syncretistic on a vaguely Christian frame a cult perhaps best known for its conduct of mass weddings linking couples hitherto unknown to each other in grand ceremonies directed by Moon himself, who, inter alia, exhorted couples to recite together the Churchs family pledge at 5 am every 8th day. The latter was syncretistic Shinto, a nation-wide organisation of believers in the superiority and purity of the Japanese people united around the emperor, much as in pre-war Japanese state Shinto. The fact that the Unification Church and Nihon Kaigi doctrines were incompatible did not seem to bother those who professed one or other, or - like Abe himself - both. Both religions extracted financial contributions from members (or sold them religious tokens and talismans), and both returned favours, the Unification Church on occasion sending unpaid volunteers sometimes as many as one hundred of them to assist in election campaigns for favoured LDP members.

In other words, despite Abe and post-Abe era professions of universal, democratic, secular values, and despite Article 20: The state and its organs shall refrain from religious education and any other religious activity, over at least the past decade (2012-2022) extremist religious cults have weighed heavily in the institutions of state. The Liberal-Democratic Party, which from 1990 had brushed aside Article 20-grounded criticisms of its religious activities and addressed itself to the Japanese electorate as a coalition with the revivalist Buddhist Komeito, from the rise of Abe to dominance of the party and state early in the 2000s took further steps to bring its political party policies in line with Moon-ish and Nihon Kaigi religious principles.

If in 2022 the Kishida government proceeds as planned to host a late September grand public spectacle in Abes honour, it will mean substantial if unknown costs being met from the public purse without parliamentary authorisation as required by Article 85, and with overtones of emperor-centred State Shinto supposedly extinguished as the emperor-centred state was liquidated and citizen sovereignty proclaimed following wars end in 1945.

As the Japan Democratic Lawyers Association (JDLA) and others have declared, a state funeral would amount to a state blessing for the Abe legacy, shifting attention away from multiple unresolved Abe-era scandals, despite its controversial and contested nature, the apparent violation of constitutionally guaranteed freedom of thought and conscience. State leaders around the world pondering their invitations to participate in the funeral events might think carefully as to whether they really want to endorse Abe’s religious causes and commitment to revise the constitution so as to enable a smooth path for Japan to become a global great power, war-capable, emperor-centred state. Are they aware that Japanese lawyers, religious and civil organisations and, it would seem, a majority of its people, contest the funeral project?

During the early 21st century decades, the rise of AUM-like religious cults accomplished a degree of penetration of the state that Aum leaders could scarcely have imagined three decades earlier. The Abe assassination and looming funeral might have become occasion for a reform of Japanese institutions to bring them back in line with constitutional principle, but it seems, instead, that the opposite process is underway, and rightists are using them to entrench their powers. During the Abe and post-Abe governments of the early 21st century, AUM-like religious cults achieved a degree of penetration of the Japanese state that their AUM predecessors could scarcely have imagined several decades earlier. Abes successors in the LDP and government continue to lay siege to the Japanese constitution of 1947.