ABUL RIZVI: Asylum Applications from China and Malaysia

December 1, 2019

Government has argued the surge in asylum applications from Chinese and Malaysian citizens is just part of normal growth in the caseload (see here). Nothing could be further from the truth. The surge is entirely the result of poor policy such as the staffing cap, Home Affairs rushing implementation of e:visas for Chinese nationals to save money and one that is slow to respond when things go wrong despite its rhetoric about being strong on border protection and immigration integrity.

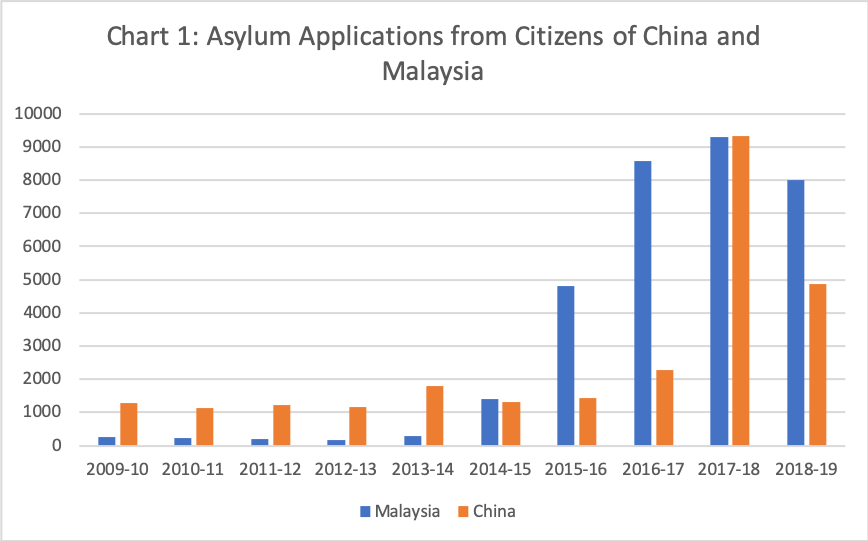

Chart 1 highlights the surge in asylum applications from Malaysia and China in recent years.

China

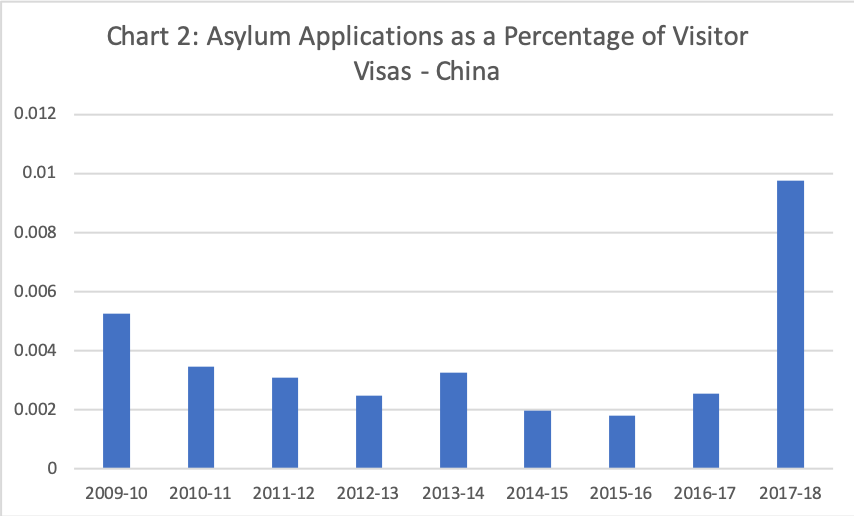

Chart 2 shows that the ratio of asylum applications as a portion of visitor visa granted to Chinese nationals grew by almost four times in 2017-18 compared to 2016-17 hardly what would be expected if integrity checking had not been reduced.

The most likely explanation is that the so-called global integrity system designed to identify visitor and other visa applications that require further checking, rolled out in 2016, was not up to dealing with the China caseload. Electronic lodgement of visitor visa applications from China was then introduced (possibly made mandatory) in February 2017. There are reports that in conjunction with these two changes, use of the auto-grant facility (ie a system generated approval facility) was ramped up.

Electronic lodgement meant the experience of local Home Affairs staff in China to spot non-genuine visitor visa applications made in paper form was lost. Moreover, use of auto-grant meant scam organisers could test and identify the types of applications being auto-granted and those that were being referred for additional checking by local staff. With this knowledge, scam organisers could profit by selling entry to Australia on visitor visas together with work rights associated with asylum applications.

It seems the scam organisers have been much cleverer than the global integrity system and the Home Affairs leadership.

The surge out of China in 2016-17 and 2017-18 is particularly odd given the extent to which asylum applications from Chinese nationals have fallen back in 2018-19 this suggests Home Affairs is slowly responding to the surge.

It remains unclear when Home Affairs noticed the increase in asylum applications from China and importantly, how it responded? Did it revert to previous systems and processes that had been successful in combating visa fraud in China? Did they allocate additional resources to deal with the emerging problem?

What is clear is that Home Affairs rushed introduction of direct electronic lodgement and auto-grant for the Chinese visitor visa caseload before adequate integrity systems were in place.

The cost of this is over 10,000 non-genuine asylum applications from Chinese nationals that will cost many millions of dollars to process at primary and review stages. Then there is the issue of what happens to the 90 percent plus Chinese asylum seekers who fail to secure refugee status and are likely to be exploited for many years to come.

Malaysia

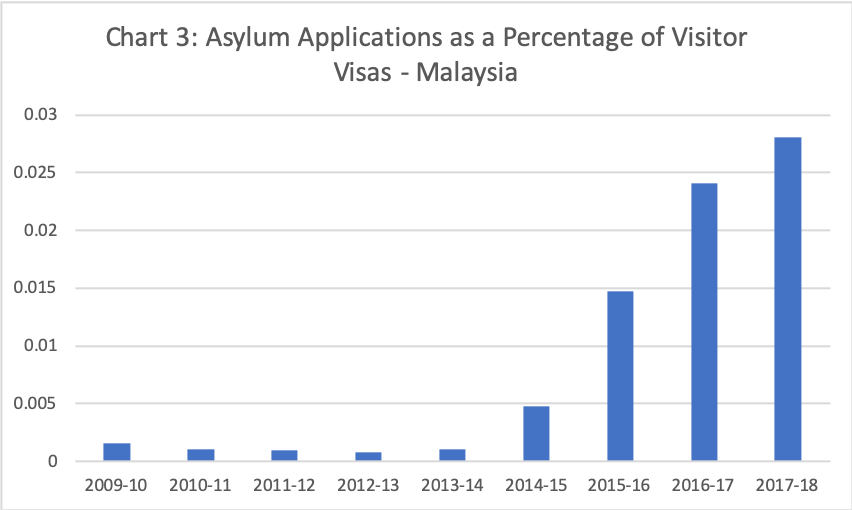

Chart 3 shows the ratio of asylum applications as a portion of visitor visa grants for Malaysian nationals increased by over 25 times from 2013-14 to 2017-18. Hardly standard growth if the visa system was operating with integrity!

The approval rate for Malaysian nationals applying for asylum remains around 1% to 2%. Indeed, during the period 2009 to 2013, it is difficult to find any Malaysian asylum claims that were approved.

The surge in Malaysian nationals applying for asylum appears entirely due to the general gridlock in the visa system and the slow processing of asylum applications in particular. That has created a honeypot for scam organisers.

Who is responsible?

Dutton and Pezzullo are the obvious culprits for this debacle.

But we should not discount the role of Finance Minister Mathias Cormann.

His Finance Department has a long history of being penny-wise and pound-foolish. Against the background of a rapidly rising caseload, maintaining a cap on the number of visa processing staff and reducing their budget is a classic example of achieving small short-term savings for massive long-term costs.

During the early 2000s, the former Immigration Department had a resource agreement with the Finance Department whereby resources and staffing levels were adjusted in line with changes in the size of the caseload. This enabled the Immigration Department to give its local managers the flexibility and authority to rapidly adjust staffing levels in line with workload.

The funding adjustments were based on marginal cost. This gave the Finance Department a budget bottom line benefit because visa application charges were well in excess of actual processing costs they in fact often exceeded average cost (visa application charges have increased significantly since then to include a large element of profit to the budget bottom line).

But even funding adjustments at marginal cost gave the Immigration Department time to implement long-term planning for a larger caseload without allowing massive backlogs to build up or into rushing changes as Home Affairs appears to have done.

The funding and staffing restrictions Cormanns Department has imposed on Home Affairs has not only led to a reduction in immigration integrity and massive long-term costs but it may have also driven Home Affairs into the foolishness of visa privatisation.

That will be where Cormann may well turn out to be the biggest culprit in the Home Affairs debacle.

AbulRizvi was a senior official in the Department of Immigration from the early 1990s to 2007 when he left as Deputy Secretary. He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to development and implementation of immigration policy, including in particular the reshaping of Australias intake to focus on skilled migration. He is currently doing a PhD on Australias immigration policies.