Albanese should share the map and the driving with the teals

May 31, 2022

One has almost to go back to World War II to find the Australian Labor Party in a more theoretically advantageous position in seeking to pursue its legislative and executive government agenda. But if Anthony Albanese and Labor are to capitalise on their luck in times almost as difficult, they must take great care in managing their relationships with those with whom they have interests in common. Too close, too intimate, will be nearly as bad as being too careless of each others sensibilities.

Labor has won a bare majority of House of Representative seats, quite enough to govern in its own right. But its unrestricted rights to get the legislation and appropriations it wants depends on the senate as well. There Labor is in a minority. The first part of the great opportunity it now has is that there are Greens and other left-oriented independents enough in the senate that Labor is not hostage to conservative forces or the sheer bastardry of pure oppositionism. The new Leader of the Opposition will not be able to apply to Albanese the tactics used by Tony Abbott between 2010 to 2013.

Just as significantly, major parts of Labors program have the support of the teal independents now so strong in number and common purpose that they have the potential to be a new party. That they come out of the centre right is, from Labors point of view, a bonus.

The independents are unlikely to become or behave as a party with caucuses and so on – because independence is, for them, both a civic virtue and a political asset. Yet everything that Labor can do to nourish and develop their sense of common purpose, and to smooth their points of difference with each other will advance the common agenda.

Likewise, it is unlikely that Labor will ever accept or regard the Greens as a part of the government. It competes with the Greens for votes, and seats. It does not yet anyway compete with the teals, although the Greens will, soon enough. But the Greens are as the teal independents are not a left of centre party, with many aims in common with Labor. They can find common ground, or, if needs be, seek to block Labors program in the senate.

It would be fatal for the teals and the Greens to be seen as co-opted by Labor, even as they work together on programs to create an ICAC, to promote a return to integrity and accountability in government decision making, in developing legislation for stronger action on climate change, and with measures designed to promote safer and more respectful workplaces. While it is Labor rather than its partners-in-arms who must be, at the end of the day responsible for the implementation of this common agenda, it is as much to each sides advantage, and in the public interest if they go about the decision-making with a sense of partnership and open debate.

PM should share the task of drafting ICAC, climate change action and respect for women. They are all on the same page.

Albanese has to a degree initiated such a process in early calls to Helen Haines. Hers is the draft ICAC-style bill already on the table, and it broadly supports the balances of investigation, standards and public accountability that all non-coalition supporters of an Integrity Bill seem to want. It would be foolish for Labor to put that work aside and fatally foolish if it adopted instead some drafting notes from the Attorney-Generals department an agency whose opposition to an ICAC bill has gone well beyond support for the minister of the day. The greens and the teals should also appreciate, if only from experience, that the politician with the most conservative and limiting agenda for an Integrity Bill will be the Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus, long house-trained by his old agency and, until it became party policy, no enthusiast for such legislation.

Albanese should consider creating a range of government committees with representation for the teals and the greens – to work together to develop common policies into workable legislation. Such committees would not be select committees with opposition representation although there is scope for them as well so much as working parties being briefed by bureaucrats and lobbies and interest groups. It might well be chaired by a teal or a green, or a government backbencher, and, of course, have ready access to the relevant minister and advisers.The purpose of such committees would not be to pre-empt proper parliamentary debate once the shape of the legislation is settled. It is to promote workable common settlements as soon as possible, so that the governments program can be advanced.

Some such committees would be sources of conflict, because members of the broader partnership would disagree about how far particular measures should go, or about the means by which they should be achieved. That is not necessarily a crisis if the dispute is in the open, and the agenda of the players is clear. It seems clear, for example, that Labors dedication to action against climate change, and to emission targets, is far more conservative than the policies on which most of the teals are agreed, and even more removed from the policies and programs the Greens would favour. Open committees are, first, a forum at which those differences are argued, and at which participants can access information and arguments which strengthen or weaken their cases. Subject to some blackmail and bargaining about what can proceed through the senate, it is the Labor governments opinion which prevails. But while that opinion, right or wrong, has a rational rather than a whimsical base, the decision is better for there having been a debate.

Such a system of managing government business (for after all ICAC, mens violence and climate action is part of the formal government platform, even if it is also the business of the teals and the greens) might seem novel in an Australian context, particularly when seen through the lens of the past 30 years. But we once had cooperative approaches to preparing and implementing new legislation FOI and the administrative reform package in the late 1970s are an example. Family law legislation worked cooperatively until the process was politicised by John Howard, Pauline Hanson and other former politicians and Attorneys-General from about 20 years ago.

Modern democracies generally have multi-party governments

These days only a few national, or even provincial parliaments, operate with only two parties, one in an absolute majority. Far more common, particularly in Europe, are shifting coalitions of two, three or sometimes seven or eight parties, often from very different ideological bases, but finding common ground as best they can. One of the good things about many such legislatures is that legislation, at the parliamentary level, is more concerned with general principles and statements of expected outcomes, rather than miles of almost impenetrable rules and regulations. The consequence may sometimes be too much rule making is in the hands of bureaucrats and tribunals attempting to put flesh on the parliamentary skeleton. Often, however, the abiding principles are clearer, and, unlike in Australia, supported by constitutional controls, such as bills of rights.

One might think that an ambitious government would not be anxious to share credit for good legislation, and good management of policy and programs and appropriations. In fact, as Albanese well knows from his time as leader of the Government in the House under Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard parliament works best and most efficiently when at least most of the parties are engaged in concert around aims broadly agreed. Julia Gillard had to wheedle almost all her legislation through a minority position in both houses yet was responsible for more legislation during a parliamentary term than any other prime minister.

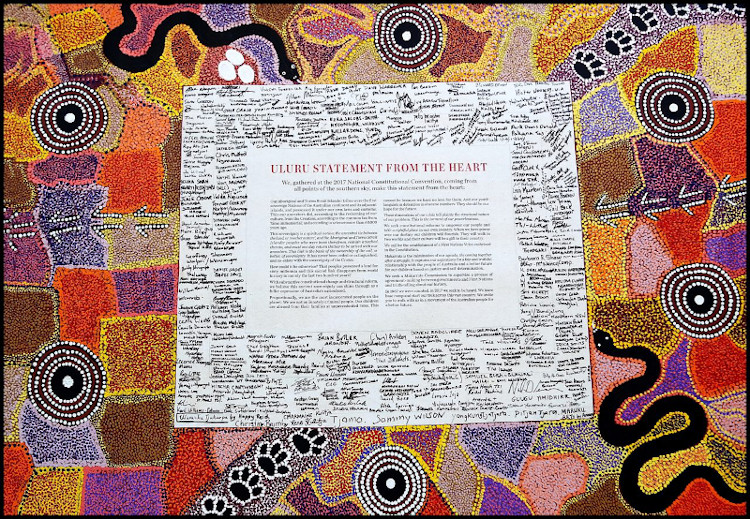

In this sense, Albanese would be smart to widen rather than narrow the field of action in which he was open to a sense of legislative partnership with both the teals and the greens. Most of the teals have expressed a positive approach to the Uluru statement from the heart.The greens have a more ambiguous approach but are positive on the broader principles, while at least a number of Liberal Party politicians are also on board with action. It does not undermine the minister, Linda Burney, nor the government, if the agenda were to proceed through an open committee process. Down the track indeed, such a cooperative approach is more likely to win bipartisan passage and popular plebiscite support.

Likewise, most proponents of focused action on integrity in government go well beyond demands for an Integrity Commission. They argue that over the past decade, but particularly during the term of Scott Morrison, old rules and controls over spending were cast aside and ignored, and pork-barrelling and direct discretionary spending by ministers rather than carefully managed grant schemes became common. The department of finance seemed to cease to be a responsible public steward, and was itself caught up in questionable administration.

Senior public servants ignored their duties under Freedom of Information and became more focused on keeping ministerial and agency activities secret rather than open and transparent. Agency heads used legal stratagems, including tactical decisions not to appeal cases going against them, to avoid facing the consequences of conscious knowledge of the fundamental illegality of some government programs, such as Robo-debt, at an ultimate cost of billions to the taxpayer. Public servants in some agencies, particularly Home Affairs, used extraordinary and improper techniques to limit their accountability to legal appeals, including spiriting people out of the jurisdiction.

Many companies who had been party donors got lucrative government contracts without tender, and the abuse of consultancies saw public money transferred to private hands without explanation, accountability, or, in some cases, even public knowledge. The ultimate responsibility for such behaviour may rest with ministers, but much of the behaviour could not have occurred if senior public servants had been doing their duty and paying as much attention to the public interest as to the service of their political masters.

Greens and teals should be partners in multiple inquiries into bad administration by the coalition

We need an array of external and independent public inquiries, and not necessarily by an Integrity Commission, necessarily more focused on wrong-doing and blame-finding than in establishing facts often previously concealed from public view.

There was once a general principle that new governments did not call inquiries into the alleged malfeasances of previous governments, but that was a principle smashed by Tony Abbott for crude (and ultimately unsuccessful) partisan advantage. It goes without saying that the number of limited faux inquiries frequently by officials who could not have been called independent — increased, became more secretive, with timing controlled for partisan purposes, and terms of reference fiddled to make proper investigation impossible. Some external and independent reports were altered, to omit unfavourable findings, in ministerial offices. These again are matters that would not have been possible without complicit senior public servants.

There are other worthy fields for inquiry, not even necessarily focused on detecting villains or misconduct. I have written several times that there should be a wide-ranging inquiry, preferably at both federal and state level, reviewing what happened with Covid-19 and the pandemic. Such an inquiry would not be designed for a witch-hunt so much as a sober review of what occurred, how decisions were made, and what we have learnt from the experience. It was a novel situation and people at all levels made mistakes. Some of these may be blameworthy, but even where no direct consequences follow, it would be a terrible thing if there was no learning from the experience and we were to repeat mistakes all over again.

Likewise, some key decisions for example over quarantine, federal and state divisions of responsibilities, lockdowns, travel bans, and the ordering, delivery and distribution of vaccines should be reviewed for management lessons the more important as some of the key players move out of the system. A key question might be the way that government used private sector providers.

That would make a good royal commission, or commission of inquiry all by itself. But it is obvious that just as much attention should go to the response by governments to the collapse of the economy, the loss of jobs, the maintenance of incomes, and government use of debt and deficit to finance what happened. No doubt there is much to be praised. But questions remain about why some groups seen as ideological enemies of the Morrison government such as universities - were excluded from assistance and some others were given billions without any controls over their eligibility, or the capacity to get back money wrongly allocated.

It is more than past time for a searching external review of anti-terrorism legislation, the use of new investigative powers given police and intelligence agencies, and the rapid creep of the use of such powers into ordinary law enforcement functions. A similar external inquiry should be investigating security agencies, including the AFP and the department of Home Affairs, and the effectiveness of intelligence agencies. They are not matters to be handed over to insiders, or left to tame and indoctrinated, and often blatantly partisan, politicians.

There are other fertile fields of inquiry, such as the efficacy of a Border Force, the independence and competence of the AFP, the management of defence acquisitions, accountability for private sector appropriations for the Great Barrier Reef, and the value for money obtained from contracted-in boat people facilities, including security.

One can expect that some in the public service would be earnestly counselling against such inquiries, if only because of bad conscience, and that some ministers with previous ministerial experience will be being reminded of the risk that inquiries would end up reflecting on the present administration, rather than the past one. Some public servants will be anxious to demonstrate that they can give this administration the same slanted service delivery given the previous one. There are Labor vested interests as crooked as any in the past administration.

On most such issues, one can expect that many of the teal independents are as predisposed to be critical of bad government and bad administration as any Green or fervent Laborite. Down the track that might become a problem when Labor ministers are misbehaving, but for the moment the focus must be on repairing obvious potholes. Its an enterprise and a mission Albanese ought to be gleefully sharing with as many fellow travellers as possible. A shared approach, particularly from open investigation, will massively increase the credibility of findings, and be a safeguard against suggestions that they are simply partisan stitch-ups.

Giving earnest and very engaged new politicians actual experience in practical legislation and administration is apt to show them the practical differences between corruption and incompetence, and realistic examples of conflict of interest, and personal and public interest. The longer that Albanese can sustain a sense of partnership and cooperation in such matters, without being accused of co-opting, compromising or coercing them, the longer he is likely to last in power.

Jack Waterford is a regular commentator and former Editor of The Canberra Times