Anointed not appointed: reign not rule

September 21, 2022

It is somewhat disappointing that in the wall-to-wall coverage of the death of Queen Elizabeth ll, there has been so little analysis of her faith which became the cornerstone for qualities that have been universally admired.

Of course, there is much to caricature, even belittle in the very nature of British royalty: how they became descendants of Queen Anne, elitism, wealth and privilege, personal scandal, the utterly bizarre way Henry Vlll was invested with the title of Defender of the faith by Pope Leo X, suppression and colonisation during their reigns, etc. We all know that.

But the reality is that most British people and perhaps the majority of Australian people saw in her qualities that united and uplifted in stark contrast to the tawdriness of political life with which we have all been recently ruled and afflicted. If you doubt her desire to serve and be one with her people, look again at the picture of her, black, masked, and alone in St Georges chapel Windsor at the funeral of her husband at the height of the pandemic while her Prime Minister was cavorting at his Downing Street parties.

How Australia became a modern nation, much loved by its inhabitants and a desired destination for many others, is quite scandalous. Later comers became prosperous at the expense of Australias first nation inhabitants. We cannot turn the clock back, but by commitment to higher ideals we can redress the past and forge a fairer and more just future. We need to immerse ourselves in first principles.

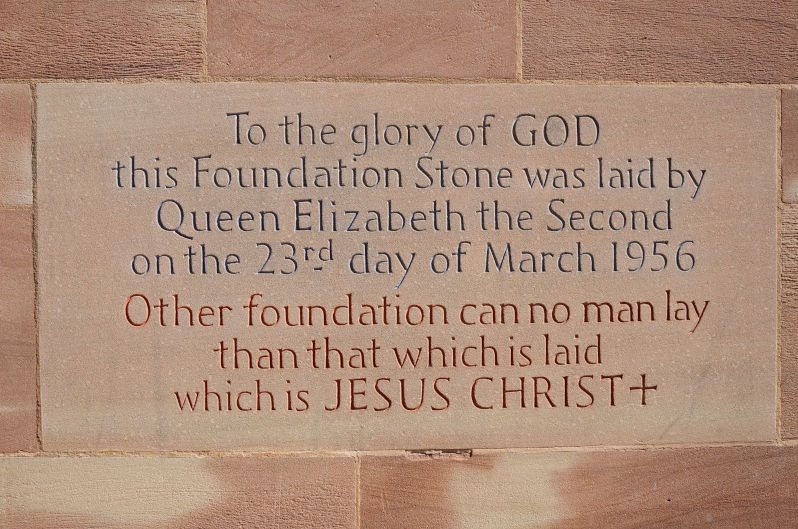

The coronation service is a profoundly religious or spiritual ceremony, not simply a civic service with overblown pageantry. More important than the placing of the crown is the moment that precedes it the anointing. With holy oil the Archbishop of Canterbury will anoint the head, heart and hands of the monarch with the sign of the cross.

When George ll was crowned in 1727, George Frederick Handel composed an anthem for the occasion called “Zadok the Priest”. It has been sung at every coronation since. Sometimes the most inciteful theologians are not clergy, but artists, poets, architects, and musicians. The lyrics for this beautiful piece are quite simple: “Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anointed Solomon king” followed by much rejoicing and God save the king!

This is a masterful composition with a lyric chock full of unchanging aspiration for shared life on this planet.

Let me explain:

In the ancient Hebrew tradition three figures existed in co-dependence in service of the people prophet, priest, and king.

It was the role of the priest to draw people beyond the often trivial, too often conflictual, usually selfish realities of human life, to a reality beyond themselves let us call this reality the divine, in whose company all are accountable. Sadly, the role of priest often then, and now, shrinks into cultic service of a particular brand, the brand seeming to have more importance than the divine itself. I have just experienced the exhibition Connections at the national museum in Canberra. Quite stunning. Clearly Australias first nations people enjoyed their equivalent of priest at the highest possible level, connecting them to everything and beyond. Western civilisation is in danger of losing the priestly class it desperately needs, those claiming to be in this class too often exhibiting a narrow and self-serving institutional dogma and ideology. Queen Elizabeth ll was shaped in the Anglican Church and unwavering in her Christian commitment, but had the capacity, as we saw in her Christmas addresses, to rise beyond cultural narrowness to the honouring of spiritual awareness that could and should be the aspiration of all.

Nathan the prophet is most famous for calling David to account for stealing the wife of one of his soldiers and then having that soldier killed. The role of prophet is absolutely essential, but quite burdensome. It is to point to injustice, where it exists, and advocate for a better, fairer, more harmonious, more just way of life, based on ideals and principles which, in a Christian context, are clear in the Gospels. Where are todays prophets? Officers of institutionalised religion? Sometimes perhaps, but sadly not often enough. They have often been scientists proclaiming inconvenient truths. They have been voices of minority groups who have challenged majority comfort. Frequently they have been the voices of the maligned, the wrongfully imprisoned and the dispossessed.

It is not easy for a monarch to speak with prophetic voice, for such engagement is likely to be interpreted as political interference. However, it is important. The new monarch will need to acknowledge and address the way in which Britain has benefited from past dispossession of others. He will need to continue his advocacy for an environmentally sustainable world. He will need to celebrate, as he has, a rich diversity of people without fear or favour. He will need to balance the cost of pageantry and history much beloved and expected by the British people, with a transparent accounting for, and distribution of wealth.

The monarch is anointed with these two identities priest - lifting us beyond ourselves, and - prophet - calling us to a fairer more just and harmonious world. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that the office of monarch exists because of these identities. The monarch does not rule. The monarch exists to embody the identity to which the people aspire, not in position or wealth, but in the virtues that undergird true human being.

In the minds of most Britains, Queen Elizabeth ll fulfilled this role on their behalf.

It is Christian belief, and certainly my belief, that in Jesus, prophet, priest, and king are fully present.

I personally believe Australia should produce its own head of state, but in doing so, finding a model through which these identities can be expected to be present will be far from easy. In presidential form, there are few heads of states anywhere in the world who commend themselves.

Charles has said he wishes to be known as defender of faiths, not defender of the faith. Rather than a diminishment of his role as head of the Church of England, I perceive this to be exactly the step that an Anglican Christian, worthy of the name, should take in a modern multi-faith world. To be Anglican is to embrace all Christians as brothers and sisters and to be Christian is to heighten and respect the spiritual awareness and distinctiveness of others.