Are you better off than 2020?

November 22, 2024

The question draws from what Trump effectively used in the closing weeks of the recent USA elections. Liberal-National Party (LNP) leader Peter Dutton is exploring a similar approach to winning government in the approaching Australian election. Employer groups are preparing to help him. Will Labor’s messaging on living standards satisfy the Australian working class?

The Annual Wage Review (AWR) is a statutory requirement of the Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA09) conducted by the Fair Work Commission (FWC). The Review determines annual pay increases for Australia’s lowest-paid workers, both the National Minimum Wage (NMW) and minimum rates in the “modern” Award system. It shapes the living standards of about 2.9 million low-wage workers (and indirectly many others).

This year’s AWR (starting in December) coincides with the next election and, is an opportunity to expose Dutton’s appeal to workers on median wages and less.

We will probably not know the specific minimum wage claims from the ACTU, employers, or governments until early to mid-March.

The gender pay gap (GPG) and “junior rates” in many awards will be 2 specific issues pursued in the union submissions.

The employers usually propose a low increase or none, commonly supported by the LNP. Probably, the Reserve Bank (RBA) will speak up against an increase. The ALP government has advocated the AWR not let workers fall behind inflation.

Low- and median-income workers deserve a significant increase that helps them regain what they have lost over the last decade.

The National Minimum Wage (NMW) and award rates

Last year’s decision at 3.75% set the NMW at $915.90 per 38-hour week, starting from July 1, 2024. It stays below the poverty line, despite recent improvements. It applied to minimum rates in all awards, including for other types of workers, e.g. with a disability and “junior” workers.

The ACTU proposed a 5% increase to the NMW and all minimum award rates.

The gender pay gap

For decades union women have highlighted a significant wage gap for women doing the same or similar work as men, reproduced in awards and enterprise agreements.

The Labor government changed aspects of the FWA09 to provide stronger powers for the FWC to close this gap in the AWR process.

Probably the ACTU will press this issue strongly in the forthcoming Review.

Youth wages

Most awards contain minimum wages for “junior” workers, apprenticeships, disabled workers, and trainees.

The ACTU is now building support to get rid of “junior” and other youth rates because these young workers are doing “adult” work no matter their age.

For example, the minimum wage for café and restaurant workers depends on the age of the worker, not the nature of the work they do. A 16-year-old working a 38-hour week, doing the same work as a 19-year-old, is paid $11.73 per hour, $8.21 less than a 19-year-old.

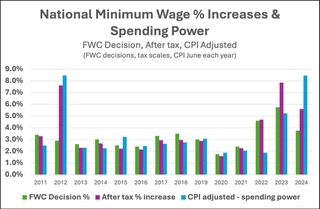

National Minimum Wage Decisions

The graph shows AWR decisions from 2011 to the current year relative to the tax bite and inflation. The green bar shows the FWC’s minimum wage decision, the purple shows its value after tax, and the blue shows its inflation value. This does not show the cumulative loss from one year to the next.

Last year, the ACTU said the average award wage in May 2021, just after the start of the pandemic, was worth about $5,200 more than mid-2024 because of inflation.

2023 and 2024 stand out because they followed recommendations from the Labor government to the AWR that minimum rates should keep up with inflation, and for 2024-5, Labor’s changes to the LNPs tax scales.

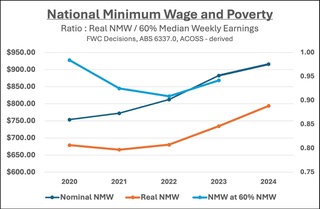

The next graph shows the NMW relative to ACOSS’ poverty line (60% median wage), starting in 2020, the last full year of government before the pandemic, when Dutton was in the cabinet. Then, the LNP had been governing for almost all the years since this AWR process had started.

ACOSS’ submission (p.15) to the AWR last year showed single workers on the minimum wage “typically” live below the poverty line and, that has worsened since 2018-19.

We see the real NMW remains below the poverty line, just as it has since the election of the LNP in late 2013, and the start last year of regaining real wages lost in the last couple of years.

This year we can compare the 2 mainstream party leaders’ commitment to lift minimum wage workers out of poverty in real terms.

Livings standards interactions

The AWR interacts with other elements in the living standards struggle.

First, profits and wages co-exist. Profits relative to wages paid to get them is the rate of exploitation. Recent data confirms the rate of exploitation is still at a historically high level.

Other important relationships include executive salaries, enterprise bargaining, prices and productivity, tax and spending in the Commonwealth Budget, and the RBA’s “management” of interest rates.

More than ever climate change and associated degradation of nature damage living standards.

Industrial action by workers to pursue their demands is a crucial but neglected dimension of the living standards struggle.

Further action: focus and strategy

The Review could lift the standard of living for millions of Australians and challenge the sincerity of Dutton’s claim to be their champion.

The ACTU’s normal approach is to submit a claim and then politely argue its case without education and organising to scale. Historically, this is right-wing unionism.

That won’t lift low-wage workers above the poverty line and thus make a crucial difference in their minds whether anyone is on their side.

It is the “same old-same old” that Dutton hopes to use, as Trump did.

Instead, the intent should be to develop a mass public campaign for a strong ACTU claim in which low- and middle-income workers build their common interest and potential power that wins higher living standards. A different strategy like this can also attract young workers into union membership and activism. They become their own champions instead of waiting for a “strong man”.