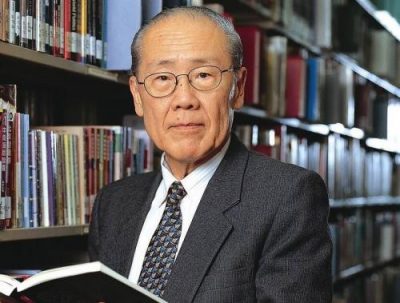

Asian voice: Wang Gungwu (East Asia Forum Oct 9, 2020)

October 18, 2020

Against the backdrop of the current tension between China and the United States, Wang Gungwu’s contribution to mutual understanding between East and West is more essential now than ever.

Wang Gungwu is among the most prominent China scholars in modern times. Born 90 years ago, on 9 October 1930, into a Chinese family living in Surabaya, Indonesia, Wang grew up in Malaysia, was educated in Singapore and the United Kingdom, and had an illustrious academic career in Malaysia, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore. One can imagine how such diverse cultural experiences influenced him as a person and scholar.

His great intellectual contribution is to the conceptualisation of the sophisticated relationship between China and the world. His work has earned him the title Junzi: Confucian gentleman, or scholar-gentleman. Drawing on his rich life experience, his deep understanding for different cultures and civilisations, his intellectual imagination and his passion for harmony between China and the world, Wang has brought closer together two distinct and, at times, seemingly irreconcilable worlds.

An overarching theme in Wang’s work is the concept of ‘Chineseness’. Wang delved into the changing nature of Chineseness from both a domestic and international perspective.

As a civilisation state, China has undergone continuous and dramatic change. Foremost a historian, Wang has studied China’s three rises: the Qin–Han, Tang–Song and Ming–Qing. Each rise brought significant changes to many aspects of dynastic politics. Wang’s interest then turned to the evolution of Chineseness in China’s modern history. After the intrusion of Western powers, the country underwent rapid and radical, even paradigmatic, changes. Throughout Wang’s career, debate has raged among Chinese and Western intellectuals on modernisation and Westernisation, which many regarded as synonymous.

While Wang acknowledged the significant shifts introduced by the West, he emphasised that, in the context of a rise in nationalism and a revival of Confucianism, China remains China. Modernisation has not turned China into a ‘Western-type’ power as many may have anticipated. Wang shows that Confucianism has endured through history, regardless of era, regime or crisis. The May Fourth Movement and the rise of Communism also could not dispel Confucianism.

On the international level, Wang wedded Chineseness to the context of Tianxia (all under heaven). More than 50 years ago, Wang first attracted international attention with an essay on Ming relations with Southeast Asia in The Chinese World Order: Traditional China’s Foreign Relations, edited by John Fairbank. It laid out the normative underpinnings and practices of the imperial tribute system, with Tianxia being its organising principle.

For Wang, central to all the issues related to China’s behaviour on the international stage today is whether it intends to impose a modern tribute system on the world. China is neither the creator of a new world order, nor is it an upholder of the existing American-led order. Instead, Wang argues that a fundamental aspect of Chineseness is the belief that everything changes; the only thing that remains unchanging is the notion of change itself.

From this perspective, the current system is destined to change. The current international order is not the international order, but rather a product of the values and interests of the Second World War’s victors. China accepts those elements of the world order that align with its own interests, but not the system as unchanging. Today’s rules, norms and institutions are neither universal nor permanent and China is neither a revisionist nor a status quo power.

This does not mean China is fated for the so-called ‘Thucydides Trap’ — or that a military confrontation between an established and a rising power is likely. Speaking from a perspective of Chineseness, Wang argues that accommodation is possible and a civilisational clash is not inevitable. First, China’s history suggests that it is a different kind of actor from other imperial powers; its aspirations are distinct from those of the United States. China’s phase of expansion ended long ago and it has not demonstrated a will for regional or global dominance through spreading its political system or rule over other sovereign nations. Second, and more fundamentally, Chineseness itself does point to an inherent respect for humanity and human dignity and the accommodation of cultural diversity.

Any danger that China poses is not in a ‘revival’ of the Middle Kingdom and a hierarchical tribute system, but rather that it could emulate imperial Japan’s behaviour, or that of the United States. If China comes to mimic or share their conceptions, then a clash is indeed conceivable. The source of the problem would be not Chineseness but the opposite: ‘un-Chineseness’.

Against the backdrop of the current tension between China and the United States, Wang Gungwu’s contribution to mutual understanding between East and West is more essential now than ever.

Zheng Yongnian is Director of the Advanced Institute for Global and Contemporary China Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), Shenzhen.

This essay is part of an EAF series, Asian Voices, celebrating the contribution of great Asian intellectuals and thinkers to the understanding of the region. This essay is the second of two published today on the occasion of Emeritus Professor Wang Gungwu’s ninetieth birthday.