Australia and the New China Threat: Globalised political opportunism

July 21, 2022

The development of a China Threat in Australian political discourse is nothing new. The apparent threat of being swamped by Chinese migrant workers played a major role in bringing the colonies together at the time of Federation, resulting in the Commonwealths White Australia Policy as the first act of the new parliament.

While at one point in the second half of the 19th Century Chinese constituted about 3.3% (40,000) of the total population of the Australian colonies, this declined to and after 1901. These numbers are of course dramatically dwarfed by the 5.5% (1.2 million) of the much larger overall Australian population who now (according to the 2021 Census) acknowledge their Chinese heritage. These days the China Threat is more usually presented as a security and political issue, even though unsurprisingly there is more than a little unfortunate spill-over into social and cultural interactions, felt negatively by at least some of those Chinese Australians as recent election results would seem to indicate.

This new generation of a China Threat is though nonetheless equally the product of political opportunism: a rallying call adopted by politicians hoping to gain support, not always only or even mainly in order to counter China. The contemporary attempt to present the Peoples Republic of China [PRC] as an existential threat to Australia particularly by way of military security issues is the clearest example of this disjuncture. In the lead up to the May 2022 Federal Election Coalition politicians, and particularly the Minister for Defence repeatedly talked about not just the China Threat to national security, but the possibility of war with the PRC. Yet at the same time, (then) Minister Dutton was on record as saying that it was unlikely that the PRC would attack let alone invade Australia directly. In Duttons view the inevitability of a war with the PRC was over Taiwan in which Australia would be expected to become involved because the USA would come to Taiwans defence. Remarkably this is of course still not the position of the US government, which for good reason prefers a position of strategic ambiguity, despite President Bidens occasional off-the-cuff remarks. And this of course is before any consideration is given to whether the PRC would want to invade Taiwan, and indeed whether it had the military capacity to do that successfully regardless of any possible US support to Taiwan beyond a condemnation through the United Nations.

The relationship between Taiwan and the PRC is far more complex than Australias contemporary political opportunists would sometimes like to suggest. The simplicity of an ideological and political conflict between the two was a function of the earlier Cold War. At the end of the 1946-9 Civil War between the Communist Party of China and the Republic of China, the latter under Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist Party retreated to Taiwan. The Republic of China (on Taiwan) was recognised as the government of China by the United Nations until 1971, and by the USA until 1979. Certainly, the PRC has always regarded Taiwan as a renegade province, and desired its absorption. This has remained an explicit long-term goal even after recognition by the USA: indeed the formal PRC policy of one country, two systems though later applied to dealing with Hong Kong was initially developed to attempt to prove attractive to Taiwan.

From the Taiwan side of the relationship, for some time even after the changes in USA and UN recognition of the Republic of China after the 1970s, government did not abandon their goal of retaking the mainland. Even when that had occurred formally in 1991 the relationship towards the Peoples Republic was and remains far from clear-cut. Taiwan is in many ways a far more developed economy than the PRC. GDP per capita on Taiwan is US$34,234 (2022) as compared to US$14,096 in the PRC. There are some on Taiwan who favour independence and some who favour what they see as re-unification. Nonetheless, as various studies have demonstrated, including a recent (February 2022) survey undertaken for the Brookings Institute, the vast majority accept a shared cultural identity but not incorporation into a Communist Party-state, favouring instead the status quo that has emerged. That status quo which has developed over the last four decades with the PRCs economic development is characterised by a very high degree of economic integration between the two, especially at present in the semi-conductor industry and various aspects of the digital economy. One of the largest Taiwan companies is Foxconn, the focus of Apple-production in Asia, with factories throughout the mainland. Taiwan exports forty percent of its manufactures to China and is the largest investor in the Mainland.

The degree of economic integration between the PRC and Taiwan and the nature of that integration in strategic industries present obvious obstacles to the formers consideration of invasion. As does the ability of the PRC to invade, conquer, pacify and then rule the island. This argument is not meant to minimise the capacities of the Peoples Liberation Army, which have certainly grown during the last four decades, but rather to emphasise the environmental constraints to a conflict seen by those Australian political opportunists talking of the China Threat as not just inevitable but also as providing an existential threat to this country. That depiction is odder still when the trade relationship between China and Australia is brought into the equation: 41% of Australian exports go to China, 32% of Australian imports come from China; and Australia had a $92.6 billion trade surplus with China, bigger than anywhere else in the world except for Taiwan, and by a long way. The end of that economic relationship that would surely result from open conflict would seem to present a more genuine existential threat to Australias way of life.

Australians might well ask in whose interests a war with the PRC over Taiwan, or indeed any kind of open conflict with the PRC, should then be considered. There is no doubt that the development of a China Threat discourse has resulted from reactions to the growth of the PRCs economic and political importance in international affairs over four decades. Australia has benefitted from Chinas economic growth and would face problems if that economic relationship came to an end. The USA on the other hand has had a hard time coming to grips with the notion that the PRC is a new rising power. A good example is a speech from Senator Mitt Romney in 2021:

We (the USA) cant look away from Chinas existential threat China will replace America. China is on track to surpass us economically, militarily, and geopolitically. These measures are not independent: A dominant China economy provides the wherewithal to mount a dominant military. Combined these will win for China the hearts and minds of many nations attuned to their own survival and prosperity

Regardless of the veracity or undesirability of the picture Romney paints, the military focus is interesting, as is the case in Australia. The USA military is three times the size of its Chinese counterpart, and military expenditure is increasing faster. Nonetheless, military interests in both the USA and Australia have seen an opportunity In promoting the possibility of a China Threat. In the USA the military advocated the need for increased expenditure when it reported to the US Senate Committee on Armed Services early in 2021 and at the start of President Bidens term that the PRC was preparing to launch an immediate or fairly immediate attack on Taiwan. In Australia the lead organisation promoting the idea of a China Threat to this country is the Australian Strategic Policy Institute whose sponsors include leading international arms manufacturers in addition to the US State Department.

While the issue of military security is central to the current case for a China Threat, it is of course by no means the whole story. The discourse of the China Threat suggests that the PRC is also subverting Australias democracy, stealing strategic technology, and buying up Australian assets. In part these arguments are undoubtedly only mounted on the assumption that the PRC government and by extension anything emanating from China does present a threat to Australias national security. Two recent pieces of legislation the extension of the Foreign Interference Act in 2018, and the introduction of a Foreign Relations Act in 2020 would seem to enshrine those messages implicit in the idea of the China Threat. It has been argued that these legislative measures were not directed at the China Threat, or at least not solely in that direction; but media attention and public perception in Australia would seem to be convinced otherwise.

It is of course possible for a foreign government or indeed other kind of political entity or social group (foreign or otherwise) to attempt to exert undue influence or even subvert political and economic processes. As a relatively well-run liberal democracy Australia has long had procedures for dealing with such cases, especially at the State level. The key to combatting undue influence and interference is not in any case censorship and protectionism of the kind provided for by the Foreign Relations Act but openness and transparency, and this applies equally to domestic and international affairs.

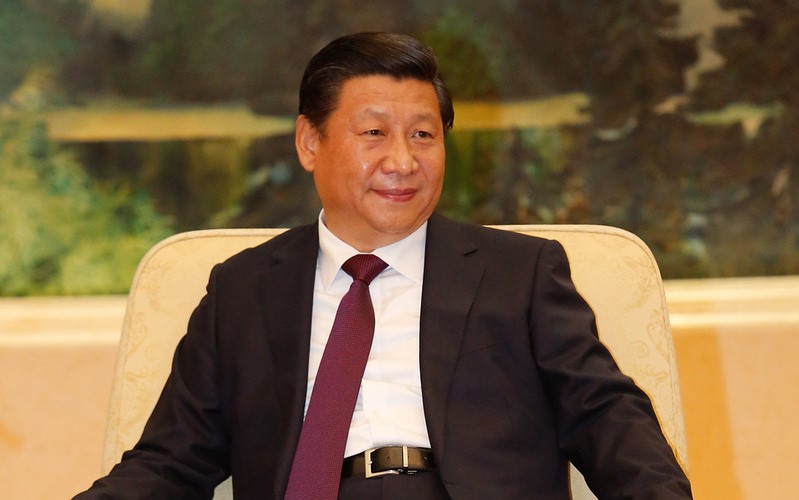

The growth of Chinas economy and its increased political influence certainly poses challenges to the international and global world order. Some will see the need for adjustment, others will inevitably resist. For Australia there is though little to be gained from demonising the PRC, Xi Jinping or indeed all Chinese, and everything to lose. This is not just an economic argument because of the potential consequences for the Australian standard of living. A sizeable proportion of the new emerging multicultural Australian society is now Chinese as well as Australian with all the variety those terms implies. Social cohesion depends on more cooperative and less politically opportunistic ways of looking at the world.