Australia-China relations are stabilising

September 29, 2023

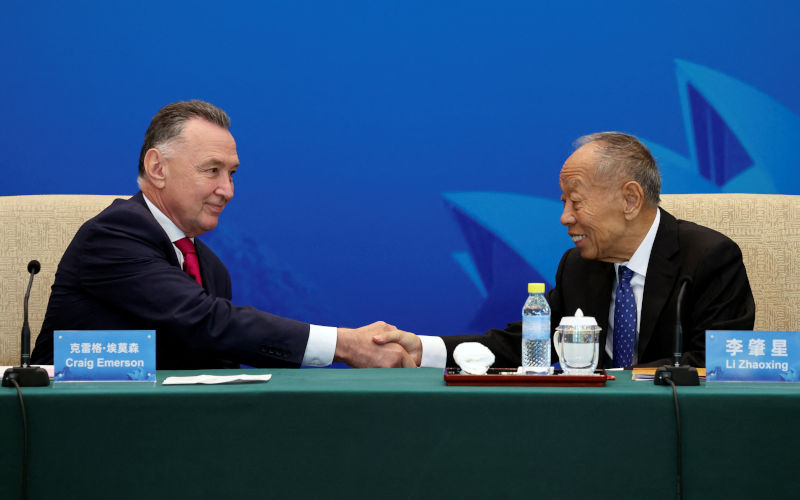

After three years pause, the Australia-China High-Level Dialogue held its 7th meeting in Beijing on 7 September. This continues the process of stabilisation in bilateral relations since the Albanese government came to power 16 months ago. A closed-door meeting where no extensive media coverage was possible, it was nonetheless understood that the two sides considered the resumption of the dialogue a good sign of progress and exchanges of views on major bilateral issues took place.

Indeed, bilateral relations have stabilised since the election of the Australian Labor Party in May 2022. A number of steps taken by Canberraand to some extent reciprocated by Beijing - have at least reversed the heretofore increasingly deteriorating ties over the previous few years, starting with the passage of the Foreign Influence Transparency law in Australian Parliament in 2018 and reaching the lowest point when Canberra proposed an international investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic. The first step that the ALP government took was to lower the temperature and refrain from engaging in megaphone diplomacy.

Second, meeting Beijing half-way, official bilateral dialogues have resumed, with ministerial meetings taking place as before, at a more regular albeit still less frequent pace. Still, these official channels offer opportunities for both sides to engage in serious conversations and present each sides positions candidly and directly rather than through counterproductive rhetoric and accusations. Most importantly, Prime Minister Albanese met Chinese President Xi Jinping during the G20 summit in Indonesia last November and recently met the new Chinese Premier Li Qiang in Delhi.

Also importantly, restrictions and outright bans on Australian imports into China have been gradually lifted over the past few months. These include barley, coal, seafood, red meat and cotton. It is reported that solutions are being sought to reduce the tariff on Australian wine in the coming weeks. These are important developments for both substantive and symbolic reasons. Obviously, trade remains a strong link in bilateral relations with significant mutual benefits. At the same time, the easing of these sanctions, imposed in the aftermath of the Morrison governments ill-fated call for the Covid investigation, suggests both sides are interested in a diplomatic thaw if not a breakthrough.

The timing also works for a reversal of the downfall. 2022 marked the 50th anniversary of Australias diplomatic recognition of the PRC. Albaneses planned visit to China later this year coincides with the 50th anniversary of Gough Whitlams visit as the first Australian Prime Minister. The newly appointed Chinese ambassador Xiao Qian has also engaged in a diplomatic charm offensive, placing stabilisation and improvement in bilateral relations top of his agenda.

Despite all this progress, there are entrenched structural factors that suggest that significant challenges lie ahead for bilateral relations. A careful assessment of these cautions against unrealistic expectations while calling for mutual restraint in managing the bilateral relationship in the coming years. Three issues are prominent: Australias alliance with the United States and its participation in US-led security arrangements such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and AUKUS; Chinas growing ties with the Pacific Islands states; and Canberras position on de-risking, including trade and investment in critical minerals. Two of these (first and third) are viewed by Beijing as anti-China and discriminatory and represent significant barriers to further improvement of bilateral relations. Indeed, if not managed carefully, they could also lead to misunderstandings and result in escalation of tensions.

The Quad has been criticised by Beijing as reflective of Cold War mentality and a US-led attempt at containing Chinas rise and its legitimate rights in economic development and its place in the region. In response to this and the US Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) concept, China has launched its own diplomatic offensives such as the Global Security Initiative as alternative approaches to building regional security architectures. However, it is the strengthening of the Australia-US alliance, from the more frequent US troop rotations and US Naval and Air Force access to Australian military facilities, that raise the spectre of misunderstanding and miscalculations, in that Beijing could perceive these as Australia becoming a convenient launch pad for US military operations in the Western Pacific against China, including scenarios regarding Taiwan.

In this context, Australias acquisition of nuclear-powered attack submarines could be seen as part of the US-led coalition in future military operations far away from the Australian continent proper. While Beijing has launched diplomatic efforts in characterising AUKUS as posing a serious threat to the international nonproliferation regime, its real concerns are the military significance of Australia obtaining and deploying such capabilities allowing it to patrol in the South China Sea and its conjunction to the Indian Ocean.

A second issue involves Chinas growing presence in the Pacific, a region close to Australia and hence often viewed as having significant geopolitical and economic value to Canberra, even though succeeding Australian governments over the past decades have largely ignored the regions concerns and economic needs such as climate change and basic infrastructure. Beijing has seized the opportunity, through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), by offering development finance and lending and building infrastructure. What has alarmed Canberra, though, is Beijing reaching security agreements with some of the Pacific Island states, most prominently with the Solomon Islands.

Canberra has countered Beijings growing presence in the South Pacific by more actively engaging its neighbours. Indeed, part of the Albanese governments diplomatic agenda since coming to power has been to approach the Pacific Forum and its member states through a series of official visits, commitments to added economic assistance, and initiatives aimed at expanding and creating economic ties and cultural exchanges. Australia is also actively engaging ASEAN, Indonesia in particular, to recover lost ground and stabilise its near abroad, by supporting the regional organisations efforts to negotiate a code of conduct with China regarding the South China Sea.

Finally, Beijing views some of Canberras economic policies, increasingly characterised as de-risking, ranging from stringent review of Chinese-origin investments in Australia and continued banning of Huawei in Australias 5G networks, as both discriminatory and reflective of politically motivated actions smacking of a Cold War mentality. For instance, one de-risking consideration is the ALP governments decision to exclude Chinese participation in investing and developing Australias critical minerals.

The past 16 months have witnessed noticeable improvement in Australia-China relations, albeit starting from a dismal state. The Albanese governments shift in diplomatic approach without substantive change of its overall assessment of the regions geostrategic realties within which Australias relations with China must be placed, has enabled the process of stabilisation to take place. This has been reciprocated by Beijing. Bilateral official dialogues at multiple levels have been restored, culminating in meetings between leaders of the two countries. These efforts have brought about progress in trade, resumption of exchanges at both the official and non-governmental levels and promise more improvement in the months ahead.

However, serious obstacles exist, which make the characterisation of bilateral relations as a comprehensive strategic partnership a misnomer, certainly a far cry from the state of affairs that the two leaders anticipated when they agreed to elevate their relationship, but perhaps something aspirational for the future. What is important, though, is for both sides to recognise that these barriers are structural, with some deeply entrenched, not receptive to change and not resulting from miscommunication. As such, it should be unrealistic and even counterproductive to set, as conditions of improvement in bilateral relations, either the removal of these barriers or even their significant modification. Both leaders have to live with these realities.

But this does not mean that they could and should not work together where they can both benefit. Trade and, to some extent, investments, remain areas of potential growth and mutual benefits. Other areas, from climate change, green energy, and even cooperation in development aid to Pacific Island countries, can be explored. The last has the potential to manage if not completely dispel misperception of hidden agendas and ill intentions.

More seriously, Beijing and Canberra should develop mechanisms for open and reliable channels of communication on activities related to security and military matters, lest these are misunderstood with much graver consequences. This is something that neither Beijing nor Canberra have intended, but they could still find themselves sleepwalking into scenarios not of their making.

Read more in our China Perspective series edited by Jocelyn Chey:

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/china-perspectives-beyond-the-mainstream-media/