Australias aborted cultural decolonisation

October 4, 2023

Over the 50 years since Patrick Whites Nobel Prize, the progressive cultural nationalists, who borrowed Whites honour, challenged a tired old elite, and then generated a new cohort of tired old elites. They had broken with Britain, but embraced America and its fantasy of the universal progressive empire that dare not say its name. The Austral-Americans were born, and became the enforcers of todays sterile regime culture.

It took me forty years and the fiftieth anniversary of his Nobel Prize to pick up Patrick White again. But when I did, it led to reflections on Australian cultural history since 1973.

It struck me as odd that so few did the same. After all, White remains our only Laureate. Many times, Les Murray was rumoured to be in the running, and this year Gerald Murnane is in the top five of the bookies candidates. Moreover, from the 1970s, White became, with Manning Clark, a patron saint of new Australian cultural nationalism. Yet paradoxically White despised the great Australian emptiness and sidestepped national identity.

Fifty years on, is Australian culture stronger, weaker or just different? If Gerald Murnane wins the prize, will a new generation of cultural nationalists swell with pride? Does the question of Australian cultural identity matter in a fragmented world of virtually identities? Do any prophets from the desert come?

When I picked up Whites novels after 40 years, I found his language retained its poetic intensity. Modernist mythology maintained its mesmerising power, such as with Vosss search for an inland sea in a cultural desert. But I could not stick with Whites social imagination. The satire retained its disdain for simple suburban life, which I could not reconcile with the reality of my experience.

White condemned the great Australian emptiness. He sanctified, like many artists of the twentieth century, the stranger who saw through barren social convention to a deeper surreality. The remark by White that he was a stranger of all time prefaced David Marrs celebrated biography. His personal myth of being an exile at home made him into a saint of the marginalised.

But White was enough of an artist to show the cruelty of the stranger. In The Vivisector, White portrayed himself as Hurtle Duffield, the cruel post-romantic artist, who spoke of how hateful petty suburban life was. The exile at home became a prophet in hate. It was the reason I stopped reading him. I was, after all, just a suburban boy.

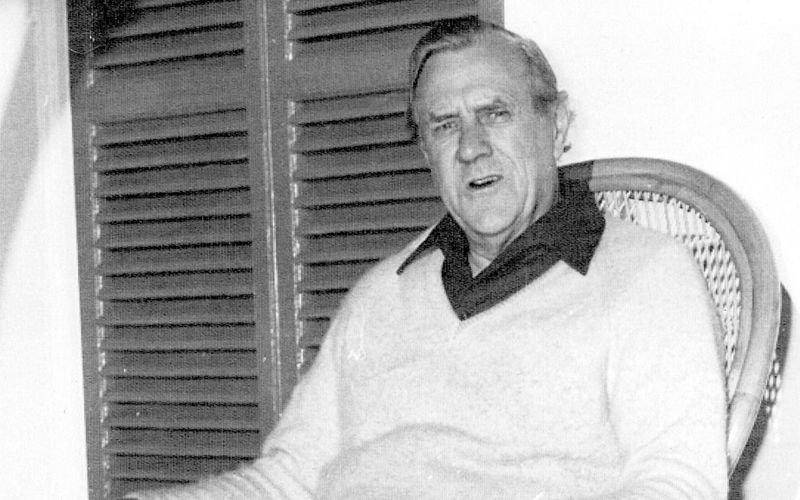

Whites Nobel Prize was announced on the heels of the opening of the Sydney Opera House. A young ABC reporter, Mike Carlton, interviewed the cagey former intelligence operative at his Sydney home. Carlton asked White whether the opening and the Prize heralded an Australian cultural renaissance.

White said no. In fact, he loathed nationalism. Carltons enthusiasm went nowhere in the interview, but would in time turn White into an icon of a progressive cultural nationalism.

White, in fiction, and Manning Clark, in history, became the symbolic leaders of those who believed themselves internal exiles in a suburban, conformist, conservative Anglo-Australian culture. They broke from the Old Dead Tree and served the Young Tree Green, as Manning Clark wrote. Yet by denouncing this wasteland, they climbed to the summit of cultural power. The stranger was honoured by the host.

The political myth of Australian culture as the Young Tree Green peaked during Paul Keatings Prime Ministership, Don Watsons tenure as speechwriter for the nation, and the Creative Nation arts policy of that era. In 2017 Christos Tsiolkas canonised White for a new progressive nationalist generation who were breaking again from a reimagined Old Dead Tree. White was the writer, Tsiolkas wrote, who gave us an imaginative language that we can call Australian, who unshackled us from the demand that we write as the English do.

There is a grain of truth in this myth of Australian cultural renaissance. White was one of many figures in the 1945-1990 generations who led Australia through a process of cultural decolonisation, very different to that experienced in Africa and Asia, but still a detachment from imperial influence. As the British Empire crumbled, and the complexion of Australian society changed, these generations created institutions and networks that exchanged ideas more freely. It was all of them, not White alone, who imagined many languages that could be spoken by Australians.

Australians told Australian stories, and they began to sell. The meaning of an Australian story became more universal, embracing and many-coloured. Australians won prizes, and became famous on the international stage and screen. The rebel culture overturned Menzies misty British Empire, but retained its pose as the voice of the outsider. Ned Kelly kept being reimagined.

But this outsider was now in power, and soaked in money. This new creative nation sold its soul to become the cultural industries. The rebirth of a nation was smothered by American consumer culture, which after 1991 proclaimed itself the universal solution of history.

Then the whole idea of a national identity, of telling Australian stories, disintegrated on impact with the internet. The cultural power of gatekeepers and prize-givers collapsed. For a while, the strangers of all time found a comfortable life on panel shows and writer festivals. There, disdain for the suburbs was no longer the expression of spiritual longing for an inland sea. It was the sneer of a fading power elite. Hatred for the suburban sprawl became adoration of inner city grunge. The yearning for the inland sea was replaced by an inundation of smut.

In the same year Patrick White won the Nobel Prize, another, more fateful omen for Australian culture appeared. The Australian film industry released the smash hit, Alvin Purple.

Over these last 50 years, the progressive cultural nationalists, who borrowed Whites honour, challenged a tired old elite, and then generated a new cohort of tired old elites. They had broken with Britain, but embraced America and its fantasy of the universal progressive empire that dare not say its name. The Austral-Americans were born, and became the enforcers of todays sterile regime culture. The Young Tree Green had spawned the Old Dead Tree.

The example of Australias aborted cultural decolonisation and the power of Whites books may yet offer hope for a cultural renewal freed of nation and American empire. But I unshackled myself from Whites imagination of this society as a cultural desert four decades ago. What I see around me is a malfunctioning, ruined theme park which blessedly offers many niches for the curious, outcast and strange. And I look to another writer of the 1970s who found in the idea of a second culture the endless fecundity of human spirit.

Two years after Patrick Whites prize, Vaclav Havel wrote in his Letter to Dr Husek (the Czech President installed after the cruel Prague Spring) that the most dangerous road for any society and culture was the path of inner decay for the sake of outward appearances; of deadening life for the sake of increasing uniformity.

People forget now, but Havel in his essays described not only the post-totalitarian Soviet states, but the contemporary, capitalist, consumerist West.

He also described the fate of Australian culture in this new era, as Manning Clark said, of years of unleavened bread.

For more on this topic, P&I recommends: