Australias modern Stanford Prison Experiment

October 14, 2022

Is Workforce Australia a modern-day Stanford Prison Experiment?

Shortly after being appointed as chair of a parliamentary inquiry into Australias $7.1 Billion employment services sector, Labor MP Julian Hill recently announced to the annual conference of the National Employment Services Association: When I read and explored the Targeted Compliance Framework and the Penalty Zone. It felt like Boston Consulting meets Squid Game in a dystopian reality TV show that we make citizens play every day.

Hill was referring to the gamified points system where unemployed workers can have their payments temporarily suspended or cancelled for failing to meet a 100-point target made up of various activities. Compliance penalties, which had been temporarily suspended due to the transition from jobactive to Workforce Australia, return this month. However, the[[[ Targeted Compliance Framework]]] has been around for several years in one form or another and has received criticism about its arbitrary nature and the capacity of employment providers to inflict harm on people whose lives are potentially already [[precarious.]]

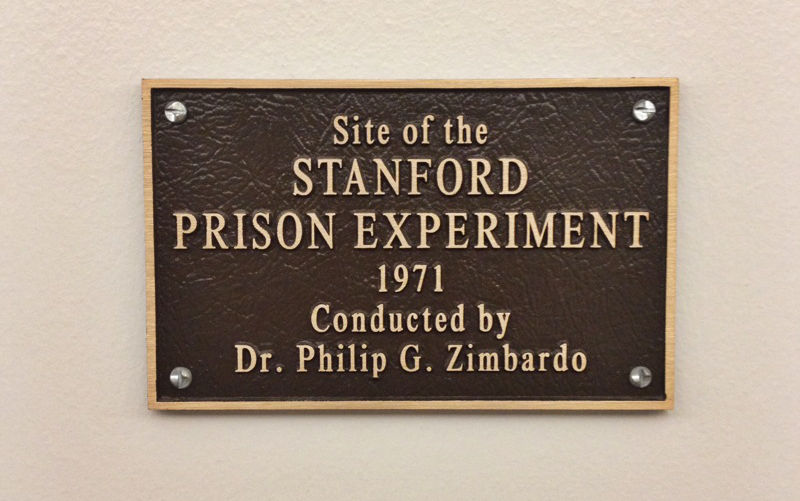

While Hill was invoking a trope from popular culture in his reference to Squid Game, he could have chosen another cultural reference The Stanford Prison Experiment to describe Australias employment services.

The 1971 social psychology experiment, which has been a staple of introductory psychology courses around the world for decades, was designed as a two-week long experiment to observe if psychologically healthy people would change their behaviour in a prison-like setting. The 24 volunteers in the experiment were randomly assigned to roles of either guard or prisoner in a mock prison set up in a basement of Stanford University. After only six days, the experiment was cancelled due to concerns about the increasing brutality of the guards and the rapidly deteriorating mental health of the prisoners. The experiment has been widely criticised, and replicating the experiment has been considered impossible for ethical reasons, although some have tried. Valid criticisms aside, the important legacy of the experiment is the question of whether humans have an innate capacity for bad, or is it that certain institutions and environments demand those behaviours? Which leads me to Workforce Australia and employment services in general.

During my PhD research, 46 per cent of the unemployed workers I interviewed told me that they had been bullied by their provider. Many also told me that their employment consultant had had no qualifications or relevant experience, while many employment consultants I spoke to told me that they had had periods of unemployment, sometimes extensive. These observations are not unique to my research. A quick search of SEEK.COM for employment consultant vacancies reveals few requiring any formal qualifications or experience. Therefore for some, a sliding doors moment (to borrow another cultural trope) could land them in either the consultant or the unemployed worker role; or should that be guard or prisoner role?

Its possible to think that employment services are the way they are because human nature tends toward the pathological, although the Stanford Prison Experiment suggests that negative behaviour flows from unfair systems and the weight of their expectations and norms. The lesson of Stanford isnt that any random human being is capable of being a bully, but that organisational cultures enable or encourage those behavioursand perhaps, therefore can change them. Bullying is something that providers and more importantly the Department of Employment could start to fix today and for next to no cost. Simply promote the clear message to all: There is no place for bullies in employment services. Mean it, and then follow through.