Australias national security strategy: no room for peace, arms control?

February 13, 2023

In contrast to Labor politicians such as Paul Keating, Bill Hayden, Gareth Evans and Gough Whitlam, the four part series recently published by Keating and Stanford on Australian national security sees no place for arms control measures and peace initiatives.

Michael Keating and John Stanford recently wrote a four-part series in P&I arguing the case for Australia to get nuclear submarines to deal with the threat from China. The series contained assertions which should not go unchallenged.

Although the last Coalition Defence White Paper did not include China in our area of operational interest, Keating and Stanford say, Its logical to assume a major area of operations for Australian nuclear submarines would be in the waters surrounding Chinas naval bases. Understandably, China could regard this as an aggressive action from Australia.

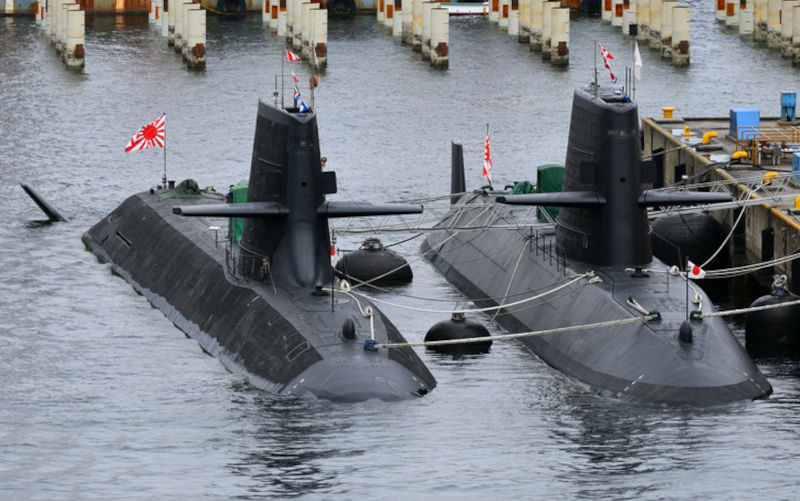

Keating and Stanford ignorethe point that there is no need forAustralian submarinesto spend much time in Chinas waters: Japan, South Korea and Singapore all have high-quality submarines closer to China. If new Australian conventional submarines occasionally need to go up to China, they can do sofrom bases in northern Australia.

Keating and Stanfordsaidone overriding problem with conventional submarines is they have to approach the surface and run their diesel generators to recharge their batteries. This makes them much more prone to detection and compromises survivability. But theydont acknowledge that this is a rapidly diminishing problem, except for outdatedsubmarines like our Collins Class which have to surface every few days.

Thanks to the long range of their advanced batteries. The latest Japanese submarines, the Taigei-class, can complete a normal mission without surfacing. Most other conventionally powered submarines except Australias use what is called air independent propulsion (AIP) which often entails using a hydrogen fuel cell to propel the submarine. This allows them to remain silent for four to six weeks before going near the surface.

The Taigei Class, which cost about $700M US each, can go as fast as a nuclear submarine. They dont need AIP because theyre equipped with particularly efficient lithium-nickel-cobalt-aluminium oxide batteries, rather than the lead-acid batteries the Australian Navy prefer. The latest batteries usually have a 1.5-times range advantage over lead-acid at lower speeds and four-times range at high speeds. Other navies are increasingly confident that new types of batteries will prove safe and match the Japanese efficiency. The South Koreans are close to operating a newly designed submarine with a new type of battery. The Germans, which are the largest exporters of high quality conventional submarines, are also committed to introducing advanced batteries.

These developments are making conventional submarines even more formidable than nuclear ones, which are easier to detect because their reactors produce hot water for a noisy steam engine and the loud meshing gears in the propulsion system. The hot water is expelled from the hull, creating an infrared signature detectable from space. Conventional submarines, which are smaller, are also much better suited to operating in the shallow waters in the maritime approaches to Australia.

Based on the latest proposals for the UK, the US and Australia to design and develop uniquenuclear submarines for Australia, the first could not be operationally available before 2050, if ever.The eight nuclear subs previously preferred were estimated to cost $200 billion and come with history ofsevere maintenance problems. The latestproposal will be even more expensive.

In contrast toLabor politicians such as Paul Keating, Bill Hayden, Gareth Evans and Gough Whitlam, the four part series sees no place for arms control measures and peace initiatives. US military spending is higher than for the next nine countries combined, including China. US spending is due to increase further, leaving room for serious cuts, as well as for China to curb its spending.

Keating and Stanford also wrote, “AUKUS is a very recent treaty. It is not a treaty. Treaties are required to be tabled for 15 or 20 joint sitting days in both houses of parliament. The Joint Standing Committee On Treaties recommends whether binding treaty action should be taken. This will take around four to six months. There is no sign this process is getting underway, nor of any publicly available text of whats in AUKUS.

To their credit, Keating and Stanford say Australia must refuse to beinvolved any conflict initiated by an ally if it is not in Australias national interest. However, they quote Kurt Campbell, President Bidens Co-ordinator for the Indo-Pacific and the father of the AUKUS agreement, as saying that with AUKUS America has succeeded in getting Australia off the fence. We have them locked in now for the next 40 years.Keating and Stanford say, This would not be acceptable, but dont explain how Australia could say No. It will be crucial to see whether the text of AUKUS,if ever released, includes a clear prohibition on the aggressive use of force in international relations.

For more on this topic, P&I recommends: Michael Keating and John Stanford four-part series

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/australias-national-security-strategy-part-1-pic-wong-albanese/?preview_id=346020&preview_nonce=9fdc05c49d&_thumbnail_id=346257&preview=true

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/australias-national-security-strategy-part-2/?preview_id=346025&preview_nonce=a380b6f106&_thumbnail_id=346040&preview=true

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/australias-national-security-strategy-part-3/?preview_id=346029&preview_nonce=087fec6fb2&_thumbnail_id=346041&preview=true

https://publish.pearlsandirritations.com/australias-national-security-strategy-part-4/?preview_id=346032&preview_nonce=1289a767c7&_thumbnail_id=306151&preview=true