Balancing diplomacy and direct action in 'Magnitsky Act' sanctions

November 24, 2021

Sponsored by a Labor senator and finessed by DFAT, a bill for a “Magnitsky Act” to sanction human rights abuses is poised to be tabled in Parliament.

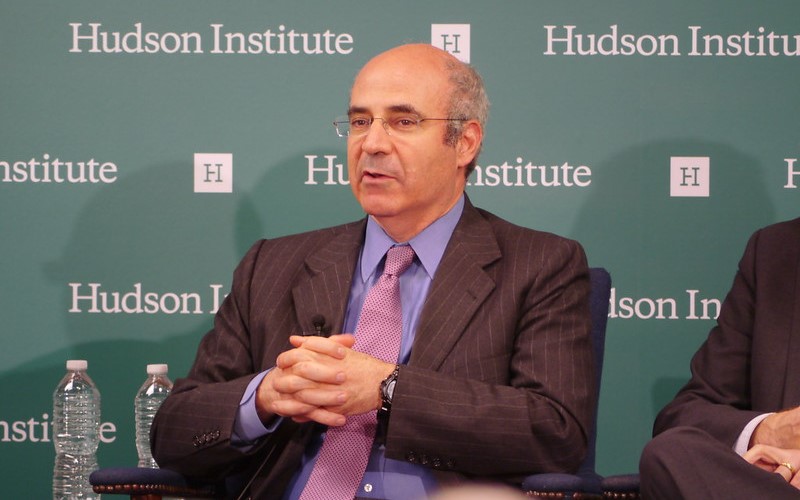

We are now in the endgame of persistent attempts by Anglo-American Magnitsky Movement campaign leader William Browder and his Australian supporters, most significantly Labor Senator Kimberley Kitching, to pass human rights laws, based on the US model, empowering the Australian Parliament to vote for “autonomous” sanctions.

These sanctions are imposed by governments outside the UN system of universal mandatory sanctions that require approval by UN Security Council resolution. In recent decades, most attempted Security Council sanctions (many on alleged human rights grounds) have been blocked by Russian and/or Chinese vetoes. In response, the Western powers have resorted to autonomous targeted sanctions imposed by various US-led coalitions.

Such sanctions are usually applied against smaller weaker countries they are the weapons of bullies but have also been used repeatedly against Russia, with disastrous effect on East-West relations. They are seen by targeted governments as internationally unlawful and vindictive acts of malice against sovereign countries. They have had no discernible human rights impact but have caused much suffering in poorer targeted countries like Cuba and Venezuela, and even in stronger countries like Iran. Used against Russia, they have simply accelerated current movement to a world divided by new Cold War tensions.

In the US, autonomous targeted sanctions are routinely legislated by the US Congress against the Russian government and major Russian enterprises, individuals who lead those entities, and their immediate families. A whole lobbying industry has grown up in Washington around the operation of these sanctions and the secondary sanctions they generate.

Their operation has soured and embittered Russia-US relations. They have tied the hands of US presidents Trump and Biden when they tried from time to time to improve these relations. They have destroyed the flexibility of US foreign policy and rendered it liable to the periodic bipartisan waves of Russophobia that wash through the US Congress.

It seems Australia is about narrowly to avoid such a fate. Browder has for years been trying to drum up public and parliamentary support here for autonomous targeted sanctions laws. A skilled and untiring campaigner, he knows how to tap into the enthusiasms of Australias human rights and ethnic diaspora communities.

His team of Australian supporters succeeded in having a parliamentary inquiry into autonomous targeted sanctions mounted in the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (JSCFADT) Human Rights Sub-committee early this year. There were 162 submissions, mostly from supporters of such sanctions mandated by vote of Parliament. Many were anonymous.

The most prominent supporting submission was from Browder himself (submission number 4). Former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans in April 2021 argued strongly in support for mandatory targeted sanctions against members of the Cambodian government and their families:

“A huge contribution would be to enact “Magnitsky” legislation so named in the UK, US and Canada to honour the Russian dissident tortured and killed after exposing government corruption to specifically target, through sanctions such as asset freezes and visa restrictions on them and their families, those powerful Cambodian government political leaders who have, so far with impunity, seriously abused the human rights of their people.

“The Australian government should follow the lead of others by now initiating and implementing, at the first available opportunity, Magnitsky legislation.”

I have recently publicly argued against such views, noting that Cambodia is a respected sovereign Asian-region country and ASEAN member, and that the time has long since passed for Australia to seek to dictate Cambodias domestic affairs through sanctions or the threat of sanctions. It would be unhelpful to Australian reputation and foreign policy in our Asian region to try to do so.

My late submission (number 145) set out the general case against any autonomous targeted sanctions against states or foreign individuals outside the Security Council rules, on grounds that these violate the principle of national sovereignty and equality of states on which the UN system depends.

I supported the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) argument that if autonomous targeted sanctions are to be included as part of Australias diplomatic toolkit, decision-making power should remain with the minister advised by her department.

Following my submission, I testified. I wrote a supplementary submission (number 145.1) under protection of parliamentary privilege:

-

In my opinion as a former senior Australian diplomat, “autonomous targeted sanctions”, the subject of this reference, violate and insult national sovereignty of states, and they violate existing widely accepted principles of international cooperation which are based on the sovereign equality of states. No nation or group of nations should have the right to pronounce judgement on citizens of other nations, or to violate their property or travel rights.

-

The campaigns pursued around the Western world by the discredited but well-funded anti-Russia propagandist William Browder, seeking to advocate laws allowing parliaments to impose targeted autonomous sanctions particularly against Russians, should not be entertained by the Australian Parliament. Mr Browder and I say this under parliamentary privilege as a witness in this committee obviously bears deep personal grudges against Russia and its President Vladimir Putin. He is supported by a very small number of Russians and Russian migrs living in the West, who are driven by anti-Putin bias. He is not in my view a credible witness, though sadly he has convinced many well-meaning people in the Western human rights movement.

Foreign Affairs Minister Marise Payne, advised by her department, responded to the JSCFADT on August 5. She accepted the principle of and occasional resort to autonomous targeted sanctions outside the Security Council system. She proposed a bill giving to the foreign minister the discretion “to impose certain sanctions for the purposes of compliance with United Nations obligations or other international obligations, or for the purposes of preventing or responding to gross human rights abuse or violations, or acts of significant corruption”.

A bill was drafted to this effect. Browders Australian supporters reluctantly accepted it as the best outcome available. On August 25, Kitching put forward, as a private members bill, the International Human Rights and Corruption (Magnitsky Sanctions) Bill 2021.

Payne welcomed the Kitching bill and promisedit would be considered by Parliament in 2021.

Last week in London, Browder awarded to Kitching the 2021 Magnitsky Award for contribution to the Global Magnitsky Movement.

The bill may go through without debate next week.