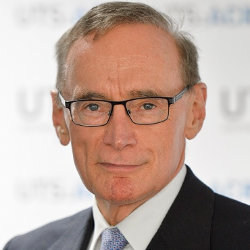

BOB CARR. The Best of 2018: How the Israeli Lobby operates.

January 1, 2019

The letter was in the bulging file marked Premiers Invites. The invitation was to an annual dinner where a peace prize was presented to a person chosen by the Sydney Peace Foundation at Sydney University. This year they had decided to present the award to Hanan Ashrawi. I knew her from CNN and had been impressed by her dignity.

I didnt want another night at an official function, no matter how worthy. Yet in the end I responded to the bugle summons of duty. I felt I had to accept. My thinking was that the Western world must reward those Palestinian leaders who choose a negotiated settlement with Israel. This would cement Palestinian support for a peaceful solution. And that would make Israel more secure, my key concern.

I had been a long-term supporter of Israel. In 1977, as a young trade union official, I had rented a room in the Trades Hall, bought some cask wine and invited Bob Hawke to come along and launch Labor Friends of Israel. I had remained its token president ever since and was always on hand to greet delegations and troop along to the Independence Day celebrations. As a young MP I stood on the back of a truck outside the Entertainment Centre, which was hosting the Bolshoi Ballet, and addressed a small Jewish rally attacking the Soviets for not allowing its Jews to emigrate. The same again, outside the Soviet Consulate in Woollahra.

In 1983 I had visited Israel with a delegation of NSW Labor people and had found it congenial enough, if not a revelation, admirable for its strong labour institutions. We met no Palestinians and were not driven around the occupied West Bank.

For years after, I had made myself available to meet Israeli delegations and visitors, mostly gloomy and dogmatic diplomats, including Mrs Rabin, whose haughty brows arched in contempt as she shrugged off questions about a two-state solution and the welfare of the Palestinians.

I and my Labor crowd were in the Zionist camp. I remember joking with John Wheeldon, a former Labor senator and a minister in the Whitlam government, about our special closeness to Israelwith its craggy old Labour Party in permanent power, its collectivised agriculture kibbutzniks who were Holocaust survivors. I entertained a notion that in retirement I might sign up as a volunteer to talk about the history of the Holocaust to counter Holocaust denial. It seemed to me self-evident that the Jews were in fact an exceptional people who had made a contribution to civilisation well above their numbers. I didnt dream that in feeding this self-image I might be encouraging a strand of thinking that, among other things, had Jews enjoying a view of themselves as the Chosen People and therefore entitled to uncontestable rights to the land God gave them.

The issue of Israeli settlements slowly wormed its way into my consciousness, but not enough to undermine my instinctual support for the Jewish state. Which brings me back to the invitation to present the peace prize to Hanan Ashrawi. I ticked the box to accept the invitation with an air of, yet another official function to keep me away from home but its good for the Jews. My attendance will reward a Palestinian leader who has signed up for a peaceful path to Palestinian statehood. Thats got to be good for Israel. The storm of criticism that then occurred was a shock, andI will develop this pointan insight.

Soon after my participation was announced, Jewish leaders launched an international petition to force me to withdraw from the award. Sam Lipski, a prominent member of the Jewish community in Melbourne, denounced Hanan Ashrawi as a Holocaust denier. There was not a shred of evidence, and he was forced to withdraw and apologise. There were threats of funding being withdrawn from Sydney University. Its chancellor, Justice Kim Santow, barred Ashrawi from even appearing in the Great Hall. Letters of protest were dispatched about the awards going to a Palestinian, switchboards set aflame with indignation.

This campaign had two objectives: to see that no Australian politician attended the presentation of the peace prize and that the peace prize be withdrawn.

An article in The Australian suggested that by accepting this invitation I had damaged the federal Labor leadership of Simon Crean and quoted an anonymous member of his staff to that effect.

Just as federal Labor is lifting its game, the NSW premier does this unconscionable thing that sets us backthis was the tone of the story planted by a member of Creans staff but not, I am convinced, by Crean himself. The day it appeared I received a call from a former colleague, Laurie Brereton, now serving in the federal parliament, who told me in strong language that I should not back down. He said, This group [he meant the Israel lobby, especially in Melbourne] is used to bullying to get its wayYou get nothing by backing off.

I had already reached the same view as Brereton. If I had backed down it would have sent a melancholic message to all Australians of Arabic or Palestinian background: namely that, through its political clout, the other sidethe lobby, the communitywill always crush you. I had given my word I would present this prize (ironically, because in one tiny way it would make a contribution to Israel being more secure). I would not back down.

I have never received more support on any single issue in my time in public life. I was stopped in the street by strangers who said, Congratulations on not backing down. It was the only controversy I can recall where this continued a month after publicity ceased.

The award dinner was a sell-out full of people from boardroom Sydney, who, I realised, had an instinctive understanding of what had gone on here: a plain bullying attempt to silence a side in the debate as legitimate as its opposite.

This is an edited extract from Me and the lobby, a chapter in Bob Carrs just-published book Run for Your Life (Melbourne University Publishing, 2018).

Bob Carr is a former Australian foreign minister and longest-serving premier of New South Wales. He is Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney.