Bridget Brennan and Kirstie Wellauer - More evidence of 'genocidal killings' of Aboriginal people in frontier times

March 19, 2022

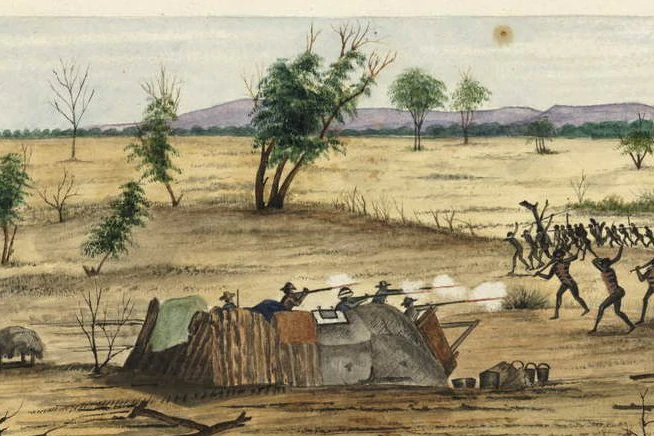

A pattern of brutal reprisals began to emerge in the late 19th and the 20th centuries as thousands of Aboriginal people were murdered in colonial times, new research suggests.

Key points:

- Professor Lyndall Ryanhas been mapping massacre sites across the country for several years

- Each site must becorroborated by multiple accounts of the violence

- The team’s latest findingsuncovered a pattern of “brutal” reprisals, especiallyin the NT and WA

During what has become known as the ‘Frontier Wars’, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and tribes fought to defend themselves and their country, with many violently murdered in the clashes with white settlers.

Now, ground-breaking research into the scale of the violence during that time suggests the massacres of Aboriginal people became “larger, more organised and ruthless” as the decades went on.

An Australian-first project, led by University of Newcastle historian Lyndall Ryan, has been mapping massacre sites across the country for several years.

When the project began, Professor Ryan said it was painstaking work to corroborate Indigenous oral history of the massacres, because thekillings were “designed not to be discovered”.

Before each massacre site is marked on the map, it must be corroborated by multiple accounts of the violence, using newspaper reports, settler diaries and letters, court records and oral history.

Professor Ryan said the team’s latest findings had uncovered a pattern of “brutal” reprisals in the period 1860 to 1930, especially in the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

Historian Professor Lyndall Ryan says massacres of Aboriginal tribes became more widespread after 1860.(University of Newcastle:Penny Harnett)

“There are more massacres and more Aboriginal people being killed so it’s taking us into a new trajectory of understanding the violent frontier,” Professor Ryan said.

Researchers now estimate more than 10,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were killed in 403 massacres, higher than the team’s previous estimate of 8,400 in 302 massacres.

By comparison, it’s estimated that 168 non-Aboriginal people were killed in 13 frontier massacres.

Massacres intensified as the frontier moved west

As European settlement expanded into the north and west after 1860, massacres intensified, researchers said.

Historically at this time, the Northern Territory was acquired by South Australia, Queensland had become a separate colony and colonial expansion into the Kimberley and into Western Australia had begun.

Push for national day to commemorate Indigenous massacres

On the eve of the 90th anniversary of the last state-sanctioned mass killing, one Aboriginal leader is calling for a national day to commemorate massacres of Indigenous people.

Accounts of many of the massacres mapped from 1860 onwards are confronting and distressing, researchers warned. “The data is telling us that the massacres after 1860 are being carried out on an immense scale,” Professor Ryan said.

She said post-1860, more colonists were armed.

“Perpetrators are becoming better organised perhaps the perpetrators are learning a lot more about how Aboriginal people are living,” Professor Ryan said.

At one site in western Queensland in 1900, colonists ambushed a tribe while they were conducting ceremony, shooting as many Aboriginal people as possible, researchers said.

A key finding of the latest stage of the map is that there are now 19 recorded ‘genocidal massacres’ of Aboriginal people.

The research team defines a genocidal massacre as a coordinated series of reprisal killings when colonists intended to kill every Aboriginal person in a region.

The Coniston Massacre in Central Australiais marked on the map and defined as a genocidal massacre.

The grave of the white dingo trapper Fred Brooks whose death was reprised by the Coniston massacre.(Supplied: National Archives of Australia)

Dozens of Warlpiri, Anmatyere, and Kaytetye people were killed in a violent campaign against Aboriginal people in the area led by Mounted Constable George Murray after the killing of white dingo trapper Fred Brooks in 1928.

In 2018, to mark the 90th anniversary of the massacre, Northern Territory Police apologised to descendants of those killed, saying the actions of officers could never be justified.

Historians believe a younger generation ‘want to make amends’

First Nations communities have long called forbetter recognition of massacre sites and stories across the country.

Over four decades, Professor Ryan has worked alongside other historians to bring evidence to light to corroborate oral history of massacres.

But their work has been the subject of fierce debate it’s one of the reasons why the map includes hundreds of sources attached to the hundreds of dots marking a massacre site.

‘We will remember them’

A landmark project mapping the murders of Indigenous tribes hits a sobering point 250 sites have been documented across almost every state and territory.

“When the debate about frontier massacres got into the media about 20 years ago, the debate was: ‘Were frontier massacres widespread across colonial Australia?’

“So, I began my research testing that hypothesis, and I found many more massacres than I ever imagined happened.”

Professor Ryan said her generation was “protected from this information”.

“I find a younger generation of schoolchildren, for example, do want to know what happened, and I do want to make amends,” she said.

“And we’re now finding that this new information in the map project itself is now becoming embedded in the school curriculum. So that’s a big step forward. “And I think it’s helping us to change our understanding of the past.”

By Indigenous Affairs editorBridget Brennanand Indigenous Affairs reporterKirstie Wellauer

This article was published by the ABC on 16 March,2022