Competing sovereignties and the voice to Parliament

May 17, 2022

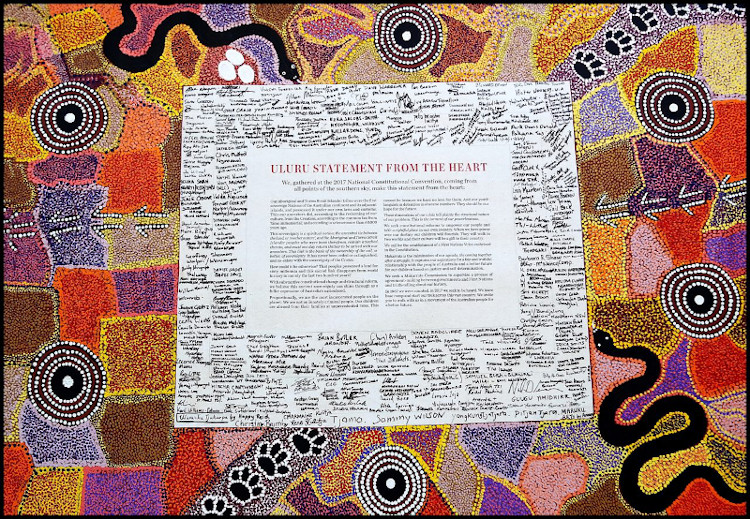

Policy towards the First Nations has attracted very little attention during the current election campaign. The Labor party has given a commitment to holding a referendum to enshrine the voice to parliament in the constitution as proposed by the Uluru Statement of 2017.

The government prefers to proceed in the same direction by legislation rather than constitutional amendment. All sides recognise the difficulty of passing a referendum which requires a majority of voters and a majority of states. But recent opinion polling is encouraging with support for constitutional entrenchment rising from 64% three years ago to 73% today.

But notwithstanding the difficulty of achieving constitutional change the voice to parliament is the most straightforward part of the reforms foreshadowed by the Uluru Statement. The linked questions of sovereignty and treaty making are much more challenging. The delegates at Uluru set down their position in words that will reverberate for many years to come:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands and possessed it under our own laws and customs.It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the CrownWith substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australias nationhood.

Which brings us to the difficult questions. If treaties are to be drafted who will be the negotiating parties? Will there be one national treaty or two, one for Aborigines and one for the Torres Strait Islanders? But what about the states? For much of our history it was the colonies/states which had responsibility for relations with the First Nations. Perhaps more to the point the states have already set out on the road to treaty making. The Victorian process is the most advanced but Queensland ,the Northern Territory and Tasmania our moving in the same direction. The new South Australian government has already declared that it will pick up the banner set aside by the recently defeated Liberal administration. So will we end up with a patchwork of quite distinctive treaties? It seems very likely.

But the proliferation may not end there. Australia may eventually follow the Canadian model of regional treaty making where the national government negotiates treaties with groups of allied Indian and Inuit communities. This process of modern treaty making has been proceeding for some time now in British Columbia and the far north where there had been no historic treaty making. Since 1975 twenty five treaties have been successfully negotiated with 90,000 people in 97 communities. The treaties vary but they commonly provide large areas of land amounting in total to 60,000 kilometres, significant capital investment, participation in resource management and local self- government.

The West Australian government has led the way with this kind of regional treaty. The so-called Noongar agreement which was finally completed in early 2021, brought together six regional communities spread across a vast area of the south-west numbering around 30,000 people. The benefits are considerable. Six Regional Corporations will receive $10 million funding annually for ten years. An overarching Trust will be funded with yearly instalments of $50 million again for a decade. There is an immediate provision of over 300,000 hectares freehold land and a substantial land fund for the purchase of more land. Public housing has been transferred to the Corporations and funds provided for future construction. The agreement did not receive universal community support and was legally challenged right up to the High Court. But it has attracted considerable academic attention and has been described as Australias first treaty. There is no doubt that it provides an attractive model for large scale regional treaty making and would likely be appropriate for the Torres Strait, Cape York, the Gulf country, Arnhem Land, the east and west Kimberley, the Tiwi Islands.

But modern treaty making has been easier in Canada than it may prove to be in Australia. Treaties have been negotiated in Canada since the C18th and were used in the second half of the C19th to facilitate the peaceful settlement of the vast grasslands between the Great Lakes and the Rockies. The jurisprudential legacy is also fundamentally different. The Indians were recognised as landowners and possessors of a form of internal sovereignty. The contrast with Australias tradition of terra nullius is inescapable. Which takes us directly to the profound contradiction between the ideas so eloquently outlined in the Uluru Statement and current interpretations of Australian law. The delegates at Uluru declared that their ancient sovereignty had never been ceded or extinguished and co-existed with the sovereignty of the Crown. If this is indeed the case it would greatly strengthen the bargaining power of the First Nations. They would come to future negotiations which a much more powerful hand. They would be in the same situation as the Indians and Inuit of Canada.

But Australian judges have shown no sympathy for this view. The prevailing interpretation remains in line with the judgement of Justice Harry Gibbs in the 1979 case of Coe v The Commonwealth. He declared that the contention that there is in Australia an aboriginal nation exercising sovereignty, even of a limited kind is quite impossible in law to maintain. And that is not all. Australian judges have agreed that our courts are unable to even question the original British claims of sovereignty made serially in 1788, 1824 and 1829. They were the result of the exercise the Crowns prerogative powers which are out of the reach of domestic or municipal courts as they are termed. In Mabo Justice Gerrard Brennan said emphatically that such questions were not justiciable in the municipal courts. Any doubts about the claims of sovereignty would threaten to fracture the skeleton of principle which gives the body of our law its shape and internal consistency.

So thats where things stand. The Uluru delegates,‘coming from all points of the southern sky’, invited the nation to walk with them in a movement of the Australian people ‘for a better future.’ We have seen above that they hoped that their ancient sovereignty could shine through as a fuller expression of Australias nationhood. But the Australian courts had declared that indigenous sovereignty does not and cannot exist, that our laws are still chained to the principles first enunciated by a handful of British officials in London 236 years ago.