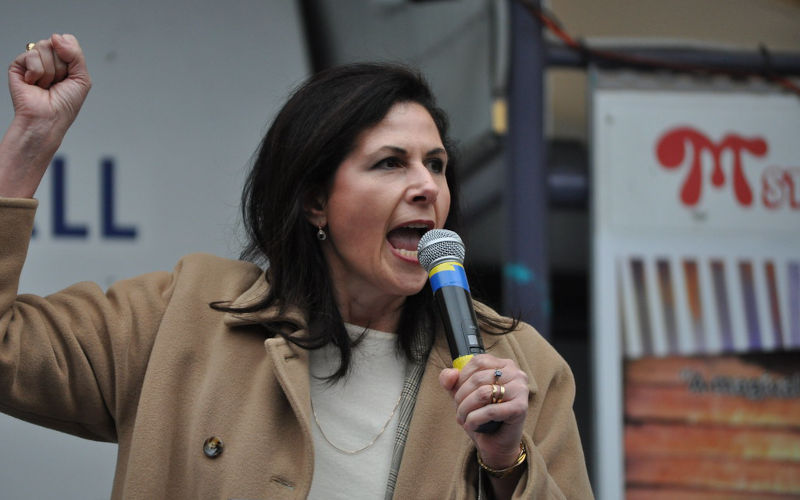

Concetta tips bucket over Morrison, a leader she despises

April 4, 2022

Senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells must resign herself to being dropped from Scott Morrisons Christmas card list for a long time.

And she must bear, with as much fortitude as she can muster, the vituperation of former colleagues who reproach her, probably wrongly, for their fate at the May election. Her farewell senate performance may be seen as raw treachery, revenge, or a belated penance for finding herself in bad company.

But it is unlikely to much affect the result. The character of Morrison was in play long before she joined the fray. What she said, very colourfully, had been said before by many others. At most she was another voice confirming a well-alleged pattern of behaviour. No-one was praising his perfume even before he received yet another bucket from the upper house.

One day, Morrison may be sitting on a park bench back at his native Bronte Beach feeding the pigeons and will blame her for his fall from grace. But Morrison has never been one for faithful recollection of what happened, and he will be deluding himself if he thinks that the senators farewell character assessment was any sort of tipping point with an election which was always going to be devilishly hard to win.

It is true that her remarks had some effect in slowing the momentum, for the government, of carefully crafted Budget announcements. But the government got most of what it wanted, because the words used by media commentators about what was there and what was not had been largely written from inside the lock-up, two hours before Fierravanti-Wells rose to speak. The media companys packages went to air or to print unaffected by later senate speeches. It was only the next morning after the economic impressions created had had some time to gel that the senators comments got any play.

It was true that the Budget coverage seemed low key. But that was not because of parliamentary distractions. The Budget, as news, was always going to be competing with renewed serious flooding in northern NSW, preparation for the Warne obsequies at the Melbourne Cricket ground on the Wednesday, and the war in Ukraine. It was, in any event, already well-known, through official budget leaks, that the Budget would have cash handouts and be election-oriented, even if it was not yet clear how hollow was its vision of anything beyond the beginning of June. Not even the most loyal News.com urgers could pretend much excitement. Fierravanti-Wells speech caused a lot of chatter among journalists drinking after the lock-up. She threw only a thimble of water on the Budget bonfire.

There are many people in the population if few in active politics who believe in and hope for the best from Morrison, whom they regard as a decent Christian man called by God to hold the fort pending His return. They have heard the calumnies and might think some likely to be true, because it is not part of their theory that he is perfect. But no matter from where the calumnies come even from a conviction Catholic such as Fierravanti-Wells they are unlikely to affect hopes for a safe return to power for Morrison. Likewise, the downfall of Morrison friends and mentors in matters of religion and life from whom, as it turns out, Morrison has been at least a million kilometres for decades does not affect their composure.

Most people have already made up their mind

Many other honourable people will support the return of Morrison, whether because they agree with his general philosophy of life and government more than that of other parties, or because they see some advantage in some campaign promise. Equally honourable people will have already determined to vote for other parties, whether on philosophical grounds too, or because of specific promises, or because they are disappointed by and disillusioned with Morrison and his government and would prefer anything but a continuation. Most voters have long made up their minds about the performance of the government, their hopes and expectations (or their fears and forebodings) about the opposition, and the characters and records of most of the players, particularly Morrison. Long before the Budget, and long before Fierravanti-Wells disappointment at her failure to be chosen for a winnable senate seat, voters had signalled low trust for politicians, particularly those in government, and a particular disinclination to believe Morrison on anything much. Those feelings had come from experience, including from occasions in which Morrison had demonstrated a lack of empathy with voters, particular problems in dealing with women, even in his own party, and where he had been repeatedly called a bully, a liar, and a phoney.

Morrison was no doubt angry and embarrassed. But hardly thrown off his stride, because he, like most politicians, has a thick hide and has been insulted by experts. It did not appear that she disrupted a vast marketing operation selling the Budget, other than through the election campaign itself. Indeed, even the outlines of the Budget marketing plan were not clear, if only because Morrison, and the Treasurer do not seem to have settled the lines of attack on the leader of the opposition, Anthony Albanese. There was yet another try-on, claiming that Albanese lacked a plan to carry the economy ahead. It was posited on Albaneses being a small target. Yet it could hardly be said that the Budget itself represented a platform for government over the next year, still less a program for the next three years, or the next decade. There were pie-in-the-sky proposals, purporting to commit vast sums of money in the outyears, but not much over the forward estimates. There were handouts, and deferral of excise for six months, but little guidance for agencies expected to manage, sometimes with seriously reduced resources. For whichever party is in government, a new Budget will be necessary in the second half of this year.

In his Budget reply, Albanese announced an array of plans in aged care an area neglected in the budget announcements, and also proposals in childcare. He raised the spectre of government cuts to Medicare and the National disability insurance scheme. Albanese seemed confident and across his material, and it was clear that he was holding back on an array of policies and programs. He gives an impression of wanting, over the course of the campaign, to seem more economically cautious, in terms of proposed expenditure, than the government, so that he can, as Kevin Rudd did in 2007, accuse the government of fiscal irresponsibility, of creating the risk of inflation, and of higher interest rates. It may prove that he has more room to manoeuvre than Morrison, given the general direction of policy including unannounced or unstressed measures that will hurt important constituencies embraced by the budget.

Mere marketing or concentration on cash handouts and a temporary petrol discount will not improve the quality of the budget. With the opposition having agreed to wave it through, the financial incentives are not even dependent on returning Morrison to power.

Morrisons plans to go to Yarralumla for an election day have not been stalled by anything Fierravanti-Wells has done. He is held up by his partys failure to preselect candidates in an array of seats, including ones which ought to be on winnable lists. He is constrained by litigation mounted by a member of his own partys machinery, and, so far, has had neither the best of the arguments or the outcomes.

The Liberals can select candidates after the election is called. But a failure to be ready suggests (indeed confirms) deep problems of party government, of party governance, and of party democracy. Even more of a problem and this involves Labor as well is that in the modern day, intervention from higher party structures seems inevitably to lead to reduced democracy, and more power in the hands of a few party leaders. Once an appeal above might have led to reinforcement of the rules; now it leads to autocracy. It seems a perverse matter that there is nothing more undemocratic than the process for choosing candidates for a democratic election.